|

by Joseph Brennan. Copyright 2002. |

Grand Central Terminal,

Passenger service:

no regular service

|

|

The Times reported on 11 December 1955 that the Westchester Chapter of the Muscular Dystrophy Association was to hold a New Year's Eve Donor Dinner Cotillion in the Grand Ballroom at the Waldorf. "To facilitate traveling to the fete, Mrs Eli Goldberg, cotillion chairman, has announced that arrangements have been made for a New Haven Railroad train to make stops at Rye, Harrison, New Rochelle and Larchmont to pick up guests from those areas and take them directly to the hotel's railroad siding." In a follow-up on 31 December, the paper noted, "The private railroad siding of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, rarely used except for Presidential visits, will receive tonight a special train" for the cotillion. In 1961 the siding was used to make a film about the "redcap evangelist" Ralston C Young, a long-time Grand Central railroad porter who held informal noon sessions in a coach in the station. The Times reported on 9 August that the Episcopal Radio and Television Foundation were making the film for showing at their convention in Detroit on 19 September. The designation "presidential siding" was possibly used simply for publicity value, and the comment in the 1955 story may be based on the name rather than on hard information. It is hard to say. By 1978, the platform was known as one of the many places in Grand Central Terminal where squatters lived, a problem exacerbated at that time by inflation and a poorly thought-through campaign to cut down on single room occupancy buildings in the city. A Times story by David Bird on 17 March 1980 refers directly to people sleeping on the Waldorf platform, "next to the elevator that once carried President Franklin D Roosevelt in his wheelchair up to the hotel from a special railroad siding". |

diagrams

Much reduced, this is a portion of a diagram of the upper track level of Grand Central Terminal revised to 1952. The area of interest is the triangular area in the upper right. Below it, tracks extend down along platforms to the station concourse across the bottom of the image. Running along the right side edge is the Lexington Ave subway, with its 51 St station at extreme upper right. Just feet outside the outer wall of the railroad terminal, it is totally separated except by public passageways at the station at 42 St (below the bottom edge of this image). The railroad enters under Park Avenue, at upper left, which expands from one level of four tracks at 57 St to the multiple tracks seen here, which have just diverged into the two levels as they approach the station. From 50 St, a pair of diagonal tracks called ladders run down and to the right, with tracks running off them to the station platform tracks. The stub tracks in the triangle at 50 St and Lexington Ave are therefore outside the main flow of traffic in and out of the station. The wide "Waldorf platform" is just under the ST. lettering in 50 St, and the elevator is next to the black spot located on the upper side of 49 St. To the right can be seen the other wide platform, formerly used for Adams Express. The Waldorf platform is between tracks 61 and 63 (there is no 62). For orientation, it is just past station platforms 11-13 and 14-15 (there is also no track 12), but it is separated from them by the ladder track. There are no station platforms at tracks 1 to 10, but they do exist; 1 and 2 are the return from the loop, and 3 to 10 are sidings. The best view from a train to the Waldorf platform would be from the right side of a train departing tracks 38 to 42 by way of the loop and thus passing into track 1 or 2 and up the ladder past the entrance to 61.

A very small portion of the same track diagram is shown closer to original size, top, and the same area is shown from another track diagram dated 1912, for comparison. A rectangle showing the building line at street level is overlaid on both images. The wide platform between 61 and 63 is the Waldorf platform. The elevator is not on the 1912 diagram, which has instead a rectangle labelled PIPE SHAFT at that location. It seems that with the powerhouse gone, the shaft was reused, for in the 1952 diagram is the same rectangle, unlabelled but with an X in it. Next to it is a stairway marked STAIRS D, and nearby a METER HOUSE just past the elevator. The other stairway to the street, on the 50 St side, is marked STAIRS E in both diagrams, near the upper left corner of the block (it's a little hard to see in the newer diagram). In 1912, this was near SUB-STATION NO 1 and a LIGHTING SUB-STATION while afterwards the HOTEL WALDORF-ASTORIA fills that space and more besides, causing some of the tracks to be cut back in length. There is an unlabelled triangular space next to the LIGHTING SUB-STATION in 1912, which had a turntable in it during construction. A photograph (below) shows an additional track leading into that space, and a Bromley real estate atlas (further below) shows a turntable. On the 1952 diagram, the space contains a TRANSFORMER VAULT, and a CIRCUIT BREAKER ROOM just off the image border. At far left is SIGNAL TOWER "A", controlling train movements on the upper level. To the right of the Waldorf platform is the Adams Express platform, which in 1912 had freight elevators up to the company's building on Lexington Ave. Although this corner of the station is only one track level deep, Adams needed access to the lower track level of the terminal, and one elevator runs down from its platform to a "trucking subway", a passageway shown by the dashed lines that runs to the express platform on the edge of the lower level. The express elevators seem to be gone in the 1952 diagram, but the passageway is still shown by faint dotted lines and is presumably still there today. Stairs D (near the Waldorf elevator) may run down to that level as well. |

|

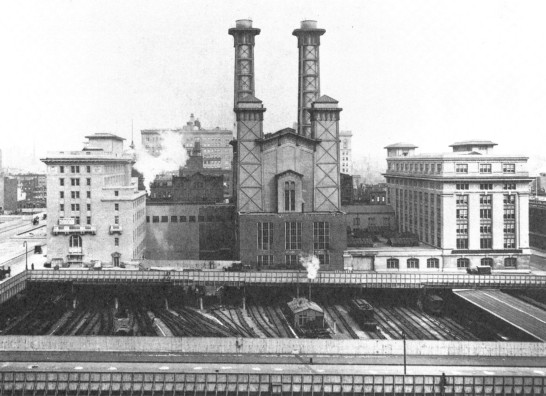

It took a few years for the Grand Central lots to be all built up. In the meantime, parts of the upper track level were open to the sky. Above, about 1914, are the YMCA, the powerhouse, and Adams Express lined up along the north side of 49 St, and behind them the electrical power building along the length of 50 St. These are substantial looking new buildings and it's hard to believe they will be torn down in just over ten years to make way for the Waldorf-Astoria. The block in the foreground is still not built upon, so the future Waldorf platform is almost visible. Reference to the track plan shows that the little building puffing smoke or steam is at the end of the future Waldorf platform between tracks 63 and 61. To the left of that, station tracks converge on Park Ave. To the right, an electric locomotive awaits action, and further right, Adams Express have a canopy over their freight platform, with just a few more tracks to the right of that. This shows how close the tracks are to street level. |

|

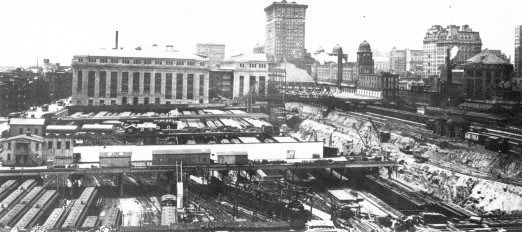

Just a few years earlier in 1908, a vast area was under construction, with train service maintained all the while. The powerhouse is not yet built, but the by comparing the views, it is possible to pick out the electrical power building running across the length of the block. As a landmark, note the peaked-roof section of the Schaeffer Brewery behind the left part of the powerhouse in both photos. (St Bartholomew's church was later built on the brewery site.) The floor of the excavation is at the lower track level, and as the foundation is finished, part of the upper track level has been built and put into use above it. The portion of the new station along the Lexington Ave side (right) was built first. A series of "bites" then carried the work across the whole station. The march of progress can be seen here, from the old station yard at ground level at far left to completed two-level structure on the right. The tracks converge on Park Ave in the left distance, where a truss footbridge still spans the street-level tracks. Looking the other way, below, in an incredible view from a vantage point up in the powerhouse, it is easier to see the old street level tracks on the right side, leading to the remaining Vanderbilt Ave side of the old Grand Central Depot even as the left side of the new Terminal goes up. The classical building straight ahead is the new Grand Central Station of the Postal Service. Beyond it out of sight is the old Grand Central Palace, an exhibition hall that had been converted to a temporary terminal, on Lexington Ave (seen at left) from 43 St to 44 St. Some trains are still using the old station too, on the other side of the work zone. The 44 St truss bridge over the old tracks is still there but not much longer. The tracks leading to the future Waldorf platform are at bottom center. |

|

Three photos: New York Central Railroad. |

|

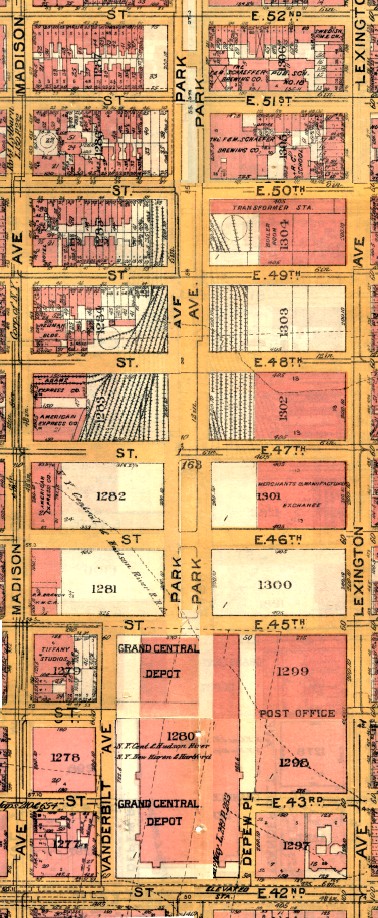

A mosaic of six sheets from a Bromley Atlas of the Borough of Manhattan, reduced in size, shows buildings in pink and empty lots in white. The detail of tracks may not be correct; the purpose of this atlas is to show buildings and property lines. Some of the Grand Central lots are already built over here, mostly at the southern end. The Lexington Ave side had been completely cleared from 43 St to 50 St during construction. North of 50 St, the blocks east of Park Ave were not changed, and the Schaeffer brewery still takes up a block and a half of Park Ave frontage that had not been so desirable when it had an open railroad cut in front of it. |

|

This is the elevator door at 101-121 East 49 St, seen in 2002. The matching bays to the left go to the hotel garage, and the closed one on the right probably once did too, since it has the protective curbs. The elevator by contrast not only has no curbs but has a small if well worn step that must annoy everyone who comes to it with a handtruck. The Waldorf-Astoria presents its best face to Park Ave, but those doors are kept shiny. |