The Biennale for Architecture

Venice, 10 September – 19 November 2006

Cities, Architecture and Society

Nancy and I have just returned from the

opening celebrations for The Biennale for Architecture in  taste of the powerful artistic experience of the show itself.

taste of the powerful artistic experience of the show itself.

The heart of the Biennale is the exhibit, Cities,

Architecture and Society, curated by our dear friend and Director of

the Biennale, Ricky Burdett. Ricky is

the Centennial Professor in Architecture and Urbanism at the London School of

Economics, and an advisor on architecture to the Mayor of London. He did, however, grow up and train in

Director, Richard

Burdett. Photo by: Hugo Glandenning

For the first time in its history, the

Architecture Biennale this year focuses on cities—on the dynamic interaction

between society and its environment, both natural and created, architecturally

and technologically. The world is becoming a primarily urban place (at the

moment, approximately half of the world’s population lives in cities; 100 years

ago, only 20% lived in cities, while the rest lived rurally; and the United

Nations predicts that by the year 2050, this will virtually be reversed, with

more than 75% of the global population living in cities), and the era our world

is entering is essentially an urban one.

According to Ricky,

..we can observe that our

urban era is a problematic one, brimming with pressing but also promising

challenges, providing the opportunity to re-design the meanings, the functions,

the aptitudes and the positive features of the various urban structures and

strategies. This is where architects and

design professionals have the opportunity and the duty to contribute to the

construction of a sustainable world, both at an environmental and at a social

level. Although each city must face its

individual and complex combination of challenges, it has been widely recognized

that some of the most common concerns will have to be tackled by practically

all cities in all the regions of the world in order to concentrate their

economic potential while increasing social equality and respect for the

environment.

Cities, Architecture and Society is an unbelievably successful presentation of these pressing and complex issues in a way that is powerful, coherent, compelling, and understandable—while at the same time being enthrallingly beautiful. The thinking behind the exhibit is heavily the result of the incredibly sophisticated, profound examination that Ricky has been doing on these topics over the past two years in the Urban Age program. A series of six world-wide conferences designed to study the problems of the city in the 21st century, the Urban Age program was an attempt to create the framework for the development of an ongoing dialogue between academic experts and urban practitioners, bringing together architects, city planners, government officials, transportation experts, real estate developers, and the academics who study these areas (q.v., my report on the New York conference of February 2005, at www.RLRubens.com/UA.htm). In the Biennale, Cities, Architecture and Society has all of the intellectual sophistication of the Urban Age program, but presented in an artistic and visually graspable form.

The main site of the Biennale for Architecture is in the Arsenale, the huge military/naval complex that takes up much of the Castello sestiere (or “sixth”—the way the sections of Venice are referred to). Begun at the beginning of the 12th century, and greatly expanded during the 14th through 16th centuries, when Venice and its mighty naval power ruled much of the world, the Arsenale was the site of Venice’s ship building and naval operations—and it remains an active military base to the present day, largely closed to the public except for the Biennale. Cities, Architecture and Society has been staged within the Arsenale, in the 300 meter-long Corderie. Its incredibly vast, unbroken longitudinal axis was for the purpose of being able to make rope there in single pieces of a dimension necessary for naval purposes; but, despite its utilitarian function, the Corderie (which was designed in 1583 by Antonio da Ponte, the same man who designed Venice’s beloved Rialto Bridge) is a fabulous building, and it provides a subtly beautiful, profoundly old, yet industrially functional backdrop for the modernity of the displays themselves—brilliantly designed by Aldo Cubic and Luigi Marchetti (of Cibi&Partners) and executed by Fragile. Also striking is the fact that the general darkness of the Corderie provides a stunning contrast to the luminous brightness of the the images of the displays.

-with the image below, as with most

of the images that follow, one may click on the image or the title for a larger

view-

Corderie, Arsenale. Photo

courtesy Fondazione La Biennale di Venezia (Asac)

One enters through a circular space, created within one end of the Corderie, on the curved walls of which space are projected 360° of video images that create a foretaste of the feel, energy, and information of what is to come. Then, down the tremendously long central axis of the building, there are a series of interlocking areas in which the urban experiences of the 16 cities of the exhibit are presented and analyzed. The cities are arranged by geographical region: Caracas, Bogotá, and São Paulo in South America; Mexico City, in Central America; Los Angeles and New York City, in North America; Cairo and Johannesburg, in Africa; Mumbai, Tokyo, and Shanghai, in Asia; and Barcelona, London, Berlin, Milan-Turin, and Istanbul, in Europe. Each city and its urban situation is presented in magnificent photographs, evocative video and audio montages which give a visceral sense of each city’s street life, drawings, plans, and graphics—many of astounding beauty, and many totally striking for the stark realities they depict. One of these realities is the simple fact of the sheer enormity of thier population size; here are the figures for their metropolitan areas, according to United Nations figures for 2005):

Barcelona 4,795,000

Bogotá 7,747,000

Berlin 3,389,000

Caracas 2,913,000

Cairo 11,128,000

Istanbul 9,712,000

Johannesburg 3,254,000

Los Angeles 12,298,000

Mumbai 18,196,000

Milan and Turin 4,153,000

Mexico City 19,411,000

New York 18,718,000

Shanghai 14,503,000

São Paulo 18,333,000

Tokyo 35,197,000

![]()

In the area on Caracas, Venezuela, for example, the images and text describe with enormous clarity the intense juxtaposition of wealthy enclaves on one side of the major highway that bisects the city and the incredibly dense barrios that have grown up on the other—“eating the hills,” as they describe it there, as they expand up the sides of the available areas of the city. These “informal cities” (the term our friend Alfredo Brillembourg uses to describe these organically self-generating neighborhoods; q.v., in the excellent volume from Prestel Press, Informal City: Caracas Case. Ed., A. Brillembourg, K. Feireiss, H. Klumpner) have meaningful local communal organization, but frighteningly-high crime rates: there are over 120 killings per week in these neighborhoods, most of them children. The exhibition describes how a low-cost, pre-fabricated “vertical gym” (created by Alfredo and his partner at the Urban Think Tank, Hubert Klumpner) that was erected in one of these neighborhoods has succeeded in reducing the murder rate by an astounding 35% in a six block radius around the gym. Apparently, many of the young people prefer playing soccer to committing crimes, when presented with the alternative!

The Vertical Gym. Courtesy Urban Think Tank

In another example, one can see the results of the efforts of another friend of ours, Enrique Peñalosa, when he was mayor of Bogotá, Colombia. Enrique restricted automobile use (allowing cars to be driven only on alternating days, according to license plate number), built an effective network of bicycle paths (an impressively large portion of the city’s population uses bicycles as its major form of transportation) and pedestrian walkways (and selective closing of certain city streets), improved public transportation, and created public green spaces and recreational areas (as Enrique points out, one of the things that the wealthy always manage to provide for themselves, but that the poor rarely have any access to is green space)—all of which created an enormously enhanced sense of hope and inclusion in society for the large number of very poor residents of his city. One thing that seems to be a clear conclusion from many of these urban experiences is that the ability to have a stake in one’s society, to feel part of the community in which one is living, is an essential element in successful urban existence—and a crucial factor in reducing crime (over the past 10 years, crime rates in Bogotá have dropped 70%).

The close and extreme juxtapositions of wealth

and poverty, privilege and need, are central realities in urban

environments. One of the most striking

photographs of the exhibit is of a luxury apartment building in

Photo: Luiz Arthur Leirão Vieira

(Tuca Vieira)

And some photographs simply capture some of the unbelievable concentration of humanity of the cities of the 21st century, as the one of the Chowpatty beach during the Ganesh Festival in Mumbai.

Some of the photographs combine an artistically beautiful image with an ugly, social problem, as one picture of the smog over Mexico City.

Mexico City, Mexico,

1999. Photo:

Armin Linke. Courtesy Galleria Massimo

de Carlo

Interspersed with the areas

about individual cities are several “issue” areas of over-arching analysis—and

these may be the most brilliantly successful parts of the exhibit. There is one fantastic such area that

utilizes satellite images pictorially to represent the environmental texture of

the created space of each of the cities.

It presents three series, each one comprised of 16 images, each 1 meter square,

one for each city: the first series, 0.3

km2 segments of each city, reduced to stark black and white by the

use of super-high contrast, illustrates the actual street plan/housing

arrangement of each city—creating a sense of the “bones” of the city’s

structure; the second, 3 km2 segments in actual colors, presents an

extraordinary feeling for the surface pattern of each city—creating a

strikingly individual sense of each city’s texture; and the third,

heat-sensitive color photographs of 300

km2 areas, showing each city’s human footprint on its environmental

geography. The sheer beauty of these

images would overshadow the revealing and informative nature of what they are

demonstrating—were it not for how incredibly powerful and immediately graspable

the points that they are making are. The

final segments of this area are two sections of wall that 1) give in numerical

form

Interspersed with the areas

about individual cities are several “issue” areas of over-arching analysis—and

these may be the most brilliantly successful parts of the exhibit. There is one fantastic such area that

utilizes satellite images pictorially to represent the environmental texture of

the created space of each of the cities.

It presents three series, each one comprised of 16 images, each 1 meter square,

one for each city: the first series, 0.3

km2 segments of each city, reduced to stark black and white by the

use of super-high contrast, illustrates the actual street plan/housing

arrangement of each city—creating a sense of the “bones” of the city’s

structure; the second, 3 km2 segments in actual colors, presents an

extraordinary feeling for the surface pattern of each city—creating a

strikingly individual sense of each city’s texture; and the third,

heat-sensitive color photographs of 300

km2 areas, showing each city’s human footprint on its environmental

geography. The sheer beauty of these

images would overshadow the revealing and informative nature of what they are

demonstrating—were it not for how incredibly powerful and immediately graspable

the points that they are making are. The

final segments of this area are two sections of wall that 1) give in numerical

form

the total population of each metropolitan area, and

2) give an indication of the geographic size of each area—cleverly and

comprehensively expressed in terms of

“how many Venices” each area

comprises.

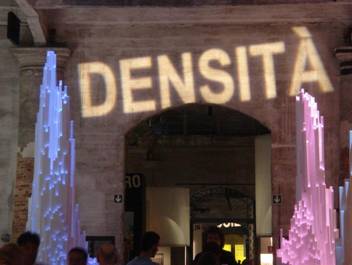

The next “issue” area is “Density.” Here are 16 white three-dimensional forms—beautifully lighted in the subdued darkness of the Corderie. Each is a graphic representation of the population density distribution of the city, with greater height indicating higher density at that geographic point in the city. These fabulous forms are at one moment elegant sculptures, populating the space of the room as striking presences, in much the same way as the cities themselves populate the global environment; and, at the same time they are high impact statements about the intensity and diversity of the population densities of the world’s major urban centers.

Manuel Silvestri/Polaris, for The New York Times

In a third “issue” area, “Mobility” is

examined. Using the vast transportation

and population data analyses of Fabio

Casiroli and the incredibly penetrating transportation thinking of Hermann Knoflacher, a series of displays have been

created. In one, there are 16 LCD

screens that graphically present the areas of each city that can access a

selection of activities (work, sports, culture, etc.) at various times of

day. The spidery, two-color patterns

(green for those areas of the population that can reach the target within the

ideal 45-minute time period, and yellow for those areas within the “acceptable”

90-minute time period) grow and vary with the changing time of day and changing

target and create forms that are informatively distinct for each city—but which

are also visually mesmerizing. In

another, transportation networks in European cities are presented in terms of

population distribution, showing both current patterns and hypothetically

projected patterns of population connectivity depending on whether one

envisions air or rail to be the predominant means of travel in the future.

In yet another “issue”

area, presented without any comment, are 16 low, horizontal, rectangular

tables, onto which, in the darkness of the unlit room, are projected from above

24 hour time-lapse sequences of the pedestrian and vehicular life of one square

in each of the represented cities.

Again, the effect is completely entrancing.

The exhibit concludes with

a series of questions rather than with conclusions. One might wish for some more evaluative

comment on what has been presented about each city; but the questions as they

are phrased—and the examples they cite and do not cite—give a subtle but

powerful sense of what the evaluations actually are—while still appropriately

leaving open-ended and alive the questions themselves.

Some thoughts from

“City-Building in an age of Global Urban Trasformation,” Ricky’s introductory essay

in the Catalog:

The quintessential urban paradox comprising confrontation and promise, tension and release, social cohesion and exclusion, urban wealth and intense squalor, is a profoundly spatial equation with enormoous democratic potential. Ultimately, the shape we give society affects the daily lives of those who live and work in cities across the world. The creation of a small gymnasium, a cultural centre, or a landscaped open space at the heart of a slum dignifies the existence of disenfranchised communities, and can fundamentally transform people’s lives. As architects, planners and city-makers we engage every day in creating the very infrstructure that can either enable social interaction or become a source of exclusion and domination. By focusing on how cities of the world are changing at global and local levels, by investigating how new forms of transport and urban design can promote social justice and equality, by exploring the links between city form and sustainability and by understanding the cohesive potential of public spaces, this exhibition provides an international perspective on the social value of architecture in cities.

The world map clearly indicates the extensive city-regions that are rapidly forming in southern Asia and coastal China, areas expected to concentrate close to half of the world’s urban population within a couple of decades. According to the United Nations, Mumbai—India’s dynamic powerhouse—is set to overtake Tokyo as the world’s largest city by 2050, but nowhere is the dazzling velocity of this transformation as tangible as in the largest Chinese conurbanations. Shanghai is now one of the world’s fastest growing cities... It continues to grow at a breathtaking rate in both height and breadth, with nearly 3,000 buildings over ten stories high in a city that had fewer than 300 only ten years ago.

In Egypt, one child is born every 20 seconds and many people move to Cairo within the space of one generation...a city with only one square metre of open space per person (each Londoner, by contrast, has access to 50 times that amount).

There is a growing awareness that the urban agenda is a global agenda. The environmental impacts of cities are enormous, due both to their increasing demographic weight and to the amount of natural resources that they consume.

From this partial and selective survey of the state of the world’s cities, we see that our current urban age is problematic, and rife with urgent challenges, yet also promising, in that it offers the potential to re-thinkthe meanings, functions, capabilities and virtues of different city forms and urban strategies.

Ricky’s exhibition is one that I spent over 5 hours absorbing during my four visits to it. (It can, of course, meaningfully be done in far less time; but I actually regret that I did not have another day to return yet again to spend a few more hours—so great is the amount and depth of what it is that is being presented therein.) Cities, Architecture and Society is of crucial importance—sociologically, politically, and environmentally, as well as architecturally and in terms of city planning; but, most significantly, it is important humanly: this is our future, and the trends and actions of the present will have a profound impact on the quality of human experience that is to come. The exhibit is a curatorial tour-de-force, the likes of which I have never seen. It is beautiful and exciting, informative and provocative, and, most of all, full of life and energy. All I can say in conclusion is, “Ricky—bravo, bravo, arcibravo!”

OTHER EXHIBITS AT THE BIENNALE

In addition to the main

exhibit that Ricky curated in the Corderie, there are other exhibits that are

part of the Biennale.

ALSO AT THE ARSENALE:

The Cities of Stone

Curated by Claudio D’Amato

Guerrieri, this exhibit examines the

Greek and Roman Mediterranean tradition of building in stone, and its

incorporation into the formation of a modernist style that is based on its

aesthetic. For an excellent description and review of this show, I refer you to

a article in the Financial Times,

written by Rachel Spence, a fascinating young art historical journalist whom we

met at the Biennale. (Click here for Rachel’s article.)

AT I GIARDINI:

As for every Biennale,

there are exhibits in the various national pavilions that are located in the

nearby Gardens. Many of these were

rather disappointing, but a few were worthy of note.

The German Pavilion was

interesting. Its theme was relatively

uninspired: called “The Convertible

City,” it basically dealt with the well-established idea of adding new,

modern elements to existing city

environments. What was quite striking,

though, was how beautifully the exhibit was arranged. Its simple, clean displays were visually very

powerful and appealing.

The Irish pavilion

exhibit, “SubUrban to SuperRural,” was an extremely thought-provoking one. Commissioned by Shane O’Toole, it begins by

noting that private home-ownership is a reality for 80% of Irish citizens, and

that this fact has led to a high degree of suburban sprawl throughout the

country, and an extremely heavy reliance on the automobile. The exhibit poses the question whether,

“accepting the road-based infrastructure and low-density housing, can Ireland

evolve new conditoins in which to live?”

The exhibit in the French

Pavilion, “Métavilla,” was refreshingly wild. As you visit the pavilion, you enter into the

space that is being inhabited by people engaged in mundane and bizarre

activities of daily life: there are

people serving drinks, there are people cooking; there are people showering,

there are people relaxing and reading.

Their space ranges from cubicles for sleeping, to soaring scaffoldings

that provide aeries from which the entire Gardens can be viewed. One can join in, or one can just observe—and

it is the ambiguity of the visitor’s role in relation to the “inhabitants”: that

makes the exhibit so fascinating. In

typically French intellectualization, it is written about the exhibit: “The occupation is the architectural face of

a social vision.” Commissioned by

Francis Lacloche, the one thing that is most true about this exhibit is that it

is fun!

![]()

Return to CULTURAL INFORMATION page.