|

|

|

|

|

|

I attended Columbia's School of the Arts from September 1972 to spring of 1975. Those three years continue to have an uncanny influence on the way I approach my art. I arrived after receiving my BFA degree from The San Francisco Art Institute, which was the polar opposite of Columbia. There, one was let loose in its hedonistic ambience, to delve without direction into any and all eccentric direction that one wanted to experiment with.

The School of the Arts was, at that time, a very conservative environment. Our professors were genuinely sincere believers in art as a process of seeking meaning. They exemplified a depth and earthiness from an earlier pre-war time. The irony was that the New York art world was teeming with radical innovations, which were the prevailing global idioms of that era: Minimalism, Conceptual Art, and the term still applied to most latter day art, Post-Modernism.

I lived in Soho, immersed in a vital energy, abounding with great force. I would take the subway to the Columbia campus, enter Dodge Hall, with a sense of straddling time. Each semester we had visiting artists of significant stature, most of whom were from the 40s and 50s, coming each week to visit student studios. Of particular note were Philip Guston and Jack Tworkov. These were remarkable people, a breed of artist now legendary. Philip Guston was especially complex and personable. He had just drastically transitioned from a famous abstract expressionist to the imagistic, cartoon-like paintings that posthumously influence art to this day. His melancholy appeared to be a manifestation of nearing the end of a long career, radically, and courageously changing the work that made his name, in an earlier generation. He anguished over this new work, not at first being met with approval. I don't think he lived to see the seminal influence his late work would have upon a generation of younger artists.

Our own faculty-in particular, Leon Goldin, David Lund, and Andre Racz-represented the end of an era, tossing to the ether, a quest one is pressed to find, in today's often puzzling art world. I was most fortunate to experience the rarified beauty of these minds.

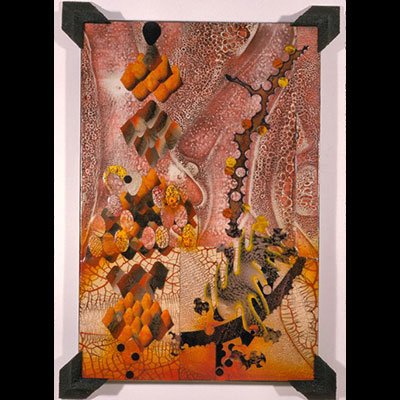

We have been accustomed to regarding living creatures as a great conglomeration of cells, and each cell as an admixture of its constituent molecules; however, from this point of view, it easily becomes almost second nature to see the living organism as simply an aggregate of its parts. But living organisms in their totality must be considered as something greater than the sum of their parts.

In my art I strive to portray the synergy between the building blocks. Should I one day succeed, I will then have arrived at a truly non-objective naturalism. Regardless, what is important is whether through careful observation it is possible to approach some idea of an order that spans not only the natural world as I see it, but the order of human thought responding to this order.

I see this especially in my reptiles, by the way they move fluidly through space. They are extraordinary models that make me see and experience space and form in a new way. Because many people have an extreme primordial fear of reptiles, I am hesitant about referring to them in their relationship to my work. I don't wish my art to be viewed by people as reptilian, because such pigeonholing limits its scope.

For me they have a clarity that is visibly external. All things in nature are governed by the same growth and formative processes as reptiles are. But reptiles reveal their mathematical structure so vividly, and working with them, holding them, and observing them is an experience filled with the rarified wonder that childhood allows. I consider using them for my art something special, and original. Consequently I expect my art to evolve into forms where art doesn't usually go. At times I feel it is already moving into that uncharted territory.

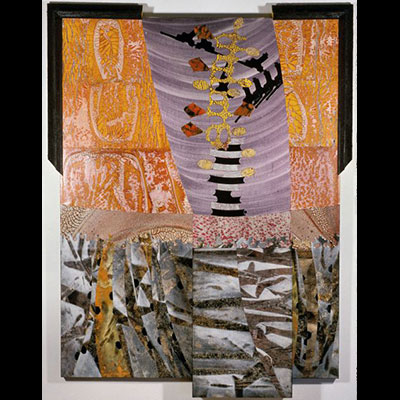

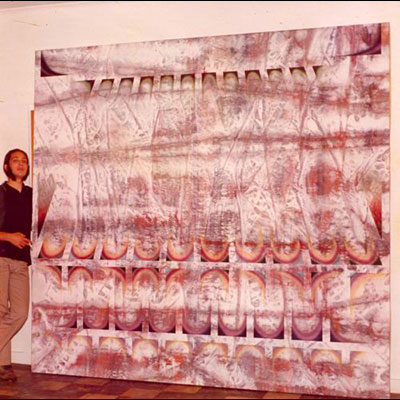

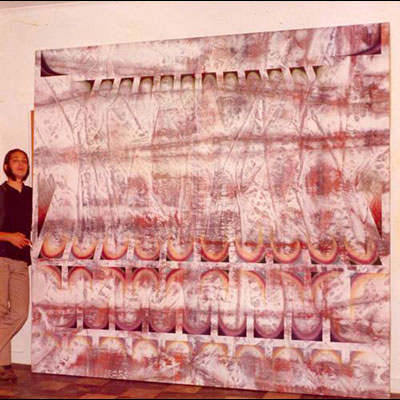

My work is never static. It's a kind of hyper-reality. Real reality is stark and fluid, yet fixed. An important aspect of the work is the perception of space. Large or small, it insists on being entered intimately. It's not work that forces itself on the viewer-even very large pieces. That's one reason I sometimes do multi-paneled works. The real spaces between each panel (interstices) force one to enter the painting very differently than if it were one square or rectangle, though I do sometimes work in that format as well. I want the eyes to go weaving through the matrix of panels, so that one is prevented from seeing it too suddenly. This process of seeing becomes almost architectural. The eye goes from "room to room" and discovers details so minute that they might otherwise be missed.

I create my paintings by imagining that they are constructed architecturally, rather than as what would usually be understood as painting. Nonetheless, I resist the term "collage" in reference to my work, because it's clearly something else. In much the same way that the cells of a living being interact with each other to create a thing greater than its machinery, I work towards creating a painting that speaks from between the lines of its structure through the medium of the structure itself.

I build paintings.