English Acquisition by Immigrants (1880-1940): The Confrontation as Reflected in Early Sound Recordings Eric Byron

Popular Songs Translated

Immigrant recording artists increased the meaning of their work by adding English to their recordings, but they also revised popular American songs in order to create novel interpretations of original compositions. They usually kept the music and some of the key English words and then reinterpreted the rest of the text to make some kind of statement that may or may not be consistent with the English version. For example, Eduardo Migliaccio, reworked the incredibly successful 1920s recording "Yes, We Have No Bananas" by Frank Silver and Irving Cohn for an immigrant Italian audience in 1923 on Victor 73980. The Silver and Cohn lyrics (and dialogue on some recordings) played upon the difficulties a non-immigrant American encounters when trying to order something to eat in a Greek fruit store. An excerpt from the Billy Jones version recorded on Edison Diamond Disc 51183 recorded circa 1923 (Zwarg) has the following:

Migliaccio keeps the title of the work, the music and a bit of English including, "Yes, We Have No Bananas" to create an entirely different composition, a portion of which focuses on the sexual associations connected with bananas.

Image: Advertisement for a Sonora phonograph published in Americky Kalendar Pre Slovakov-Luteranov, n.d. Translation: "Sonora Phonograph. Buy one of these machines to have more fun at home, its voice is nice and sounds clear. It won the highest prize at the fair in Panama. Price 55.00 and up." Translated by Tomas Vajda. Courtesy of the Immigration History Research Center.

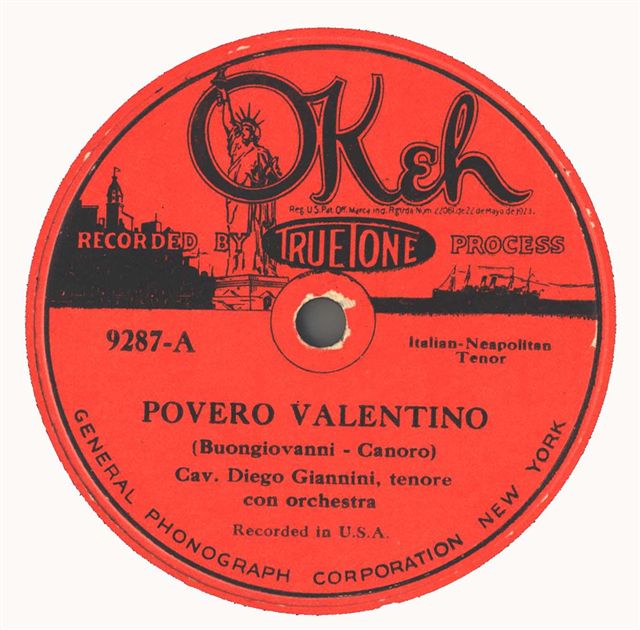

"Yes, We Have No Bananas" is not the only example of a non-immigrant recording in English that was remade by and for immigrants that plays on a sexual motif. The database suggests that there are others, such as the 1927 "Jak To Ozenic Sie Gdy" or (It Ain't Gonna Rain No More) by Dwojka Warszawska on Okeh 11325 for a Polish immigrant audience.

Of all the reinterpreted recordings that the database has so far listed, Eduardo Migliaccio's "A Do Fatico Giova" Italian adaptation of "Where Do You Work-a John?" must certainly be one of the most fascinating. In the original version by Mortimer Weinberg and Charles Marks, two Italians stereotypically discuss in English with an Italian accent the kind of manual work they do and the work that is available. The exchange takes place in a barbershop and starts off in the 1927 (Settlemier) Columbia 875-D version with the entrance of an Irish customer who wants a shave. The Irish customer speaks in standard American English and most likely acts as a foil to the Italian accented, broken English with which the Italians converse.

The 1927 Victor 79157 pressing of "A Do Fatico, Giova" utilizes the same music and periodically English words and phrases such as "me push" and "work in the subway." However, unlike the general American version, this variation wants the audience to understand the need for work, any work that will provide an income.

Of course, many of the immigrants, and certainly their children, did learn English, and gradually the recordings reflect the linguistic ease with which these people lived in the United States. Over time, the use of ethnic languages tends to diminish until there may be just enough ethnic words in a composition to imply that the record belonged to a specific group. For example, in the post-World War II recording "I Found Gold, " performed by Lee Tully on Jubilee 3504, only the Italian names "Luigi" and "Giusepp" make the recording Italian. The rest of the song uses English words.

Researchers can presently access the database in the Ellis Island Immigration Museum library. Copyright restrictions limit putting the entire database on the Internet, but at some point it may be possible to share a modified version online. In order to continue to pursue the work, transcriptions and translations of these recordings are needed, particularly those recorded for the ethnic market. Currently, there are hundreds of recordings in immigrant Yiddish and various immigrant Italian dialects that should be reviewed. Please contact the Park if you have the time and interest to undertake this challenging but rewarding volunteer work.

Eric Byron is the Coordinator of the Ellis Island Discography Project at the Ellis Island Immigration Museum of the National Park Service. He can be reached at (212) 363-3206 ext. 153.n