After a while, nothing seems strange in a stadium with a

"lid"

from Smithsonian, January, 1988

by Claude Charlier

Photographs by Gerd Ludwig

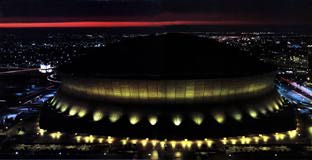

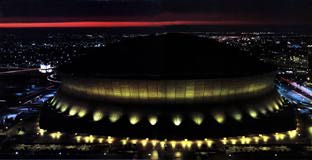

Sun seldom sets on an idle Superdome, a marvel of engineering that has

transformed its one-seed New Orleans neighborhood into a prosperous

mecca. At night, stadium glows like a visitor from anotherplanet.

On the afternoon of January 3, l962, seven armed men in cowboy hats met

on the outskirts of Houston. The site was dismal, known for damp summers

and mosquitoes the size of turkey buzzards. At the appointed hour, the

men took their Colt .45s, fired them into the earth and thus broke ground

for a stadium to house the city's new baseball franchise, a team then

known as the Colt .45s and now called the Astros. The men were also

breaking ground-or so many Houstonians

were ready to argue-for a new millennium in American sports. The building

they were about to put up was no mere ballpark but an indoor sports

theater, a palace even, with upholstered seats, air-conditioning and a

Louis XIV bedroom in a VIP suite, all under a steel dome spanning 642

feet. "This is going to be the sports showplace of the nation," said

Judge Roy Hofheinz, president of the Houston Sports Association. "Others

will follow us. Ballplayers will be dying to play in our stadium." In

truth, Casey Stengel, the garrulous manager of the New York Yankees, took

one look at it before an exhibition game a few years later and declared,

"This here's the kind of building where from the outside you can't tell

where first base is." Batters learned to dread the Astrodome, which

became known as the "doom dome" because so many hard-hit balls seemed

mysteriously to fall short. But Hofheinz spoke wisely when he said other

cities would follow. It wasn't long before folks over in New Orleans were

declaring their intention to make the Astrodome look like "a peanut

stand," and in time the city's colossal Superdome-a squat, cooling tower

of a building wrapped in a metallic corset-did take over as one of the

sports showplaces of the nation, even without a baseball team. Since

the Astrodome opened in 1965, 15 enclosed stadiums have gone up under

roofs of steel, wood or, most often, fabric. The newest dome, in St.

Petersburg, Florida, is due for completion in 1989-a grand gesture of

civic optimism, since there is no guarantee that a professional baseball

or football team will start up there anytime soon. A handful of other

cities (Phoenix, Atlanta, Orlando and San Antonio) now have domes planned

or proposed.

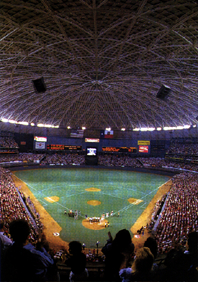

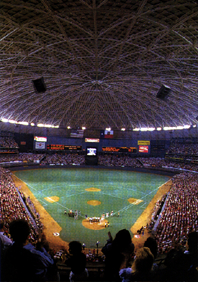

Interior photgraph of fans and dome by -- F. Calter Smith.

Interior photgraph of fans and dome by -- F. Calter Smith.

caption: Houston fans watch baseball game

in air-conditioned comfort at the Astrodome,

which opened in 1965.

Circus tents and ridged potato chips

Or rather, what they have on their drawing boards are buildings

called domes. In classical architecture, as with St. Paul's

Cathedral in London, a dome wasn't a dome unless it had a roughly

hemispherical shape. But that ceased to be true with the Astrodome's

first imitator, the Idaho State University Minidome, a stadium in

Pocatello shaped like a Quonset hut (students called it the

"half-Astrodome"). The word "dome" has since come to describe any place

big enough to accommodate baseball or football-but with a lid. In some of

the latest schemes, the lids resemble circus tents, saddles, ridged

potato chips. These domes have been labeled modern-day cathedrals,

civic icons, the symbols by which cities declare their status as

world-class players. They have changed not just the architecture but also

the economics of urban life. They have certainly reshaped American

sports-notably at the last World Series, in which, some people asserted,

the Minneapolis Metrodome should have been named the Most Valuable

Player. Domes have become forums for religion and politics as well. When

Pope John Paul II visited New Orleans last year, 55,564 people heard him

speak at the Superdome (where another 27,561 people watched Tulane

University play football that evening). And when the Republicans nominate

a Presidential candidate at the Superdome this summer, theirs will be the

first, but surely not the last, dome convention. After a little more than

a quarter-century, we are knee-deep in what one sports trade journal

terms the "dome age."

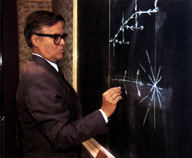

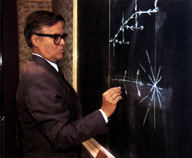

David Geiger, designer of the Hoosier Dome

David Geiger, designer of the Hoosier Dome

and other innovative stadiums, illustrates the

principles of "tensegrity" concept on blackboard.

The Hoosier Dome

The Hoosier Dome

Judge Hofheinz, a self-described huckster with slicked-back hair and

heavy black-framed eyeglasses, liked to say that it all began with a

visit to the Colosseum in Rome. A guide there told him that when the

weather turned nasty, slaves would pull a velarium, or awning, across the

ancient stadium; the idea took hold in his imagination, bearing fruit in

the form of the Astrodome. Actually, the dome idea was around before

Hofheinz ever went to Rome. In 1955, the Brooklyn (now Los Angeles)

Dodgers had commissioned architect and geometrician R. Buckminster Fuller

to design a domed replacement for Ebbets Field. Fuller had also drawn up

a similar dome for the Tokyo Giants. But no stadium ever used Fuller's

geodesic scheme, which was deemed uneconomical. Indeed, cost was the main

reason that, after the Astrodome, only two major domed stadiums went up

under any kind of rigid roof: the Superdome, which used a steel

framework, and the Kingdome in Seattle, which was built with cement.

What really got the dome boom going was an outlandish entry in the

architectural competition for the U.S. exhibition hall at Expo '70 in

Osaka, Japan. Davis-Brody, a New York firm, designed a sort of pumpkin on

top of an inverted pyramid, together 30 stories high. The pumpkin was to

be built of fabric and held up by air, a type of structure that until

then had been used to house only tennis courts and military radar

installations. The architects scouted around for an engineer who could

flesh out the design concept and they wound up with David Geiger, then a

young adjunct professor at Columbia University. The design won, but

Geiger found himself stuck with a site that was prone to earthquakes and

150 mile-an-hour typhoons. Then Congress came up with less than half the

expected budget. In desperation, the design team took a vertical cross

section of the pumpkin and laid it flat on the ground, preserving the

blocky, superelliptical outline-and very little else-from the original

plan. The result was almost a nonbuilding. It consisted of an earthen

berm topped by a concrete ring and enclosed two and a half acres under a

vast fabric lid. But it set the pattern for most of the domed stadiums

built since then. A system of fans held up the fabric roof by boosting

air pressure inside. A web of cables thrown over the top secured the

fabric and divided it into pillowy sections. Figuring out the cable

pattern was the hardest thing, even with the help of an advanced

computer. Geiger found that a standard grid, with cables crossing at

right angles, caused the roof to sag at the perimeter. But one Saturday,

in a moment of inspiration, he realized he could eliminate the problem by

running the cables diagonally. This "skewed symmetry" still characterizes

almost all such roofs.

Chef greets guests in Superdome suite while

Chef greets guests in Superdome suite while

Louisiana State University plays Nebraska in

1986 Sugar Bowl.

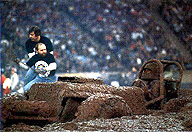

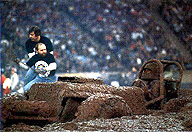

During Hoosier Dome event called National Mud

During Hoosier Dome event called National Mud

and Truck Pull, officials watch vehicle churn

in slime.

Dancers entertain crowd during a halftime

Dancers entertain crowd during a halftime

contest between bands of college teams playing

in Superdome.

The Hoosier Dome in downtown Indianapolis

is one of eight air-supported domes in this country that Geiger went on

to engineer after the triumph at Osaka. Visiting it, you get a sense of

both the magical simplicity and the underlying complexity of the design.

On this particular evening, the dome floor has become a fairground with

amusement park rides for families attending a national convention of

county officials. Politicians with their feet up ride three abreast down

a long slide, while their children turn shades of pale on the

Tilt-A-Whirl.

A support column that's made of air

The space is so vast that it's possible to forget you are indoors, much

less tilting and whirling headon into an architectural support column-a

continuous column of air maintained at a pressure slightly higher than

the pressure outside. You tend to notice only at the emergency doors or

at the hatchway onto the roof, where the air pressure suddenly turns into

a 35-mile-an-hour wind at your back.

George Shopp, dome-bellied and with his pockets full of keys, small

clipboards, a two-way radio, a beeper and other paraphernalia, stands on

the roof he is charged with keeping airborne and describes some of the

little headaches of the job. If the upper-level lavatories go unused for

a week, for instance, the unrelieved air pressure will blow the water out

of the traps, pushing enough warm air out of the plumbing vents to heat

about two houses through a Midwestern winter. And when the National

Football League Colts (lured here from Baltimore by the dome in 1984) are

in a close game, Shopp has to figure out how much to tweak up the air

pressure through the fourth quarter. He does this in anticipation of

60,000 fans suddenly exiting through 24 wide-open doors. If the pressure

goes too high, they might hurtle out; if it's too low, the dome could sag

several feet.

When the midwinter skies dump six inches of wet snow in an hour, Shopp

has to calculate how much pressure he needs to support the extra weight

and how fast to get the snow melted. A heavy hand on the snowmelt switch

can cost $250,000 because it means the Hoosier Dome will have to pay the

surge rate for electricity during the next year. Some stadiums send crews

onto the roof with fire hoses and shovels or, if the snow is dry, simply

tauten the Teflon-coated fiberglass to let the wind blow it clean. But

rivalrous feelings in the dome game extend even to maintenance, and Shopp

disdains these foreign methods as stressful to the fabric. Whereas the

control rooms at conventional stadiums devote their fancy electronics to

lighting, scoreboards and instant replay television, the possibility of

deflation gives the roof priority at the Hoosier Dome.

Guard checks fabric roof of Silverdome in Pontiac,

Guard checks fabric roof of Silverdome in Pontiac,

Michigan. Electric fans boost air pressure for support.

"Grasshopper" rolls up artificial turf in Superdome.

"Grasshopper" rolls up artificial turf in Superdome.

It takes four or five hours to remove an entire field.

Gauges monitor wind speed on two sides, roof height (which varies from

188 feet to 193 feet at the center), air pressure, temperature and

humidity. There are switches to control 20 six-foot-high turbine fans (it

takes only two to keep the roof up, unless the doors are open) and an

eight-zone snowmelt system. The awful possibilities make for interesting

work. "If you assume you know what you're doing on this," Shopp says,

"about that time it's gonna getcha."

Deflations, while bad, aren't usually all that bad because the roof will

hang up over the spectator area even when bellied down. But when the

Silverdome in Pontiac, Michigan, deflated under heavy snow in March 1985,

the fabric tore on some lighting framework and high winds whipped it like

a sheet on a clothesline. A weather radar system now watches over the new

roof, whlch cost $10 miIlion. At the Metrodome in Minneapolis, a 1986

incident led to a partial evacuation during a Twins game attended by

32,000 people. When wind shear hit one side of the roof, the control

system registered it as a surge in the building's air pressure and,

instead of tautening the roof against the wind, automatically began

dumping air to compensate. The 10,000-pound light banks and the

ceiling-hung speakers started to sway, and plugs in the roof popped,

pouring water down the third-base line. Spectators on the upper decks had

to evacuate, using revolving doors to avoid further loss of pressure.

Some people panicked and there were minor injuries. After nine minutes,

the roof stabilized and the game resumed. But such incidents are one

reason why engineers have developed new ways to put up domes.

The trend toward retractability

Perhaps the most ambitious, the Toronto Skydome will open next year under

a complicated steel roof said to be retractable in just 20 minutes. Local

boosters are already hyping it as the "world's first convertible with

60,000 bucket seats," and Toronto architect Rod Robbie happily asserts

that his roof will make "what Geiger does obsolete." It won't be a true

dome, but an assemblage of curved sections that can separate, so that

some can pull back from above the playing field and telescope inside the

others, leaving 90 percent of the stadium open. In this respect, it will

outdo the partly retractable fabric cover recently added to Montreal's

Olympic Stadium. Skydome officials say that the roof will cost them $53

million, and they have lately upped their estimate for the entire stadium

to $178 million.

Retractable roofs have always been the dream, going back to Hofheinz's

notion of the Roman velarium; they combine freedom from rainouts with the

promise of "baseball like it ought to be"-in the sun. But rivals tend to

dismiss the Toronto facility as a pie-in-the-skydome. "You spend all that

money for air-conditioning and then you spend all that money to open it

up again," says an Astrodome executive. "What for? A nice day? What's

nicer than having a nice air-conditioned building? You must have a lot of

money to do something that foolish."

David Geiger also nurses rivalrous doubts. He argues that if you take a

lot of concrete (and dome tour guides are inexplicably proud of their

concrete-at the Hoosier Dome, for instance, they mention a 36mile-long,

two-lane highway's worth), bake it in the sun for a few hours, then snap

the roof shut to fend off a sudden rain, you are liable to cook a few

fans. On the other hand, even ordinary domed stadiums can blow $10,000 a

day on heat when they wheel in steel grandstands from a cold warehouse.

"It's like putting a big ice cube in your bathtub," says Bob Haney, the

operations director at the Silverdome.

"Bucky fell in love with triangles"

For the St. Petersburg stadium, Geiger has veered off in an entirely

different direction. It will have a nonretractable fabric roof held up by

cables rather than by air. He says he was inspired this time by the

economics of litigation. Having been sued in connection with several

deflations, he wanted to come up with a dome that would be as cheap as

his air-supported structures but without wagering his future on good

weather and the diligence of maintenance crews. He thought back to

Buckminster Fuller's domes. "Bucky fell in love with triangles," says

Geiger, now 52, with wavy, disheveled gray hair and wearing

tortoise-shell bifocals. "He made his fame with the geodesic dome, which

was essentially triangulating the surface of the sphere." But Fuller also

had another concept, the "tensegrity" dome, which never got off the

drawing board. His geodesic domes were built of rigid structural elements

under compression; the tensegrity dome would depend largely on structural

elements under tension. In a sense, it's the difference between an igloo

(compression) and a tent (tension). Geiger developed a modified

tensegrity configuration for St. Petersburg's dome. All the cables pass

through a single point at the center of the roof. These cables are

supported at intervals by vertical posts, which in turn stand in midair

on a system of four concentric cable hoops. Other cables, running

diagonally, hold posts and hoops in place, under tension. The roof will

weigh two to four pounds per square foot, versus one pound for an

air-supported roof and 30 to 40 pounds for a steel roof, and it is

designed to stand up to weather without special care.

Detroit Lions go through an afternoon practice in

Detroit Lions go through an afternoon practice in

part of Silverdome still surfaced for football.

The arena for basketball has already been set up

to accommadate a Pistons contest scheduled that

evening.

Ask anybody what effect these domes have had on American life and you

will probably get the one-word answer, "AstroTurf." It is now almost

folklore that the Astrodome's 4,596 skylights produced blinding glare for

players fielding pop flies, that using an orange baseball didn't help and

that, in the end, painting the skylights killed not just the glare but

the natural grass on the playing field. The solution was a synthetic

grass substitute, promptly dubbed AstroTurf.

If AstroTurf were the only effect the domes have had, it would be pretty

small potatoes, especially considering the hoopla that has attended their

coming. When civic leaders elsewhere talk about the benefits of a domed

stadium, they invariably cite the example of New Orleans: no longer a

backwater but a prime venue for the Super Bowl, the NCAA Final-Four

basketball championship, a national political convention, the Rolling

Stones and the Pope. They talk about national television exposure and

about economic impact. The dome comes off as nothing less than a

miraculous instrument for urban renewal.

The thing is, says Geiger, you can build a dome downtown. Conventional

open stadiums gravitate to the outskirts of the city, where land is

cheaper and there is ample room for parking. With only 15 or 20 major

events at a football stadium or 81 games at a baseball stadium, it's hard

to justify paying downtown real estate prices. But with a lid, Geiger

says, an ordinary stadium becomes "an entertainment machine" capable of

accommodating 250 events a year and, when it is located at the center of

the city, hotels and restaurants tend to spring up around it. The

succession of big-time events booked into the Superdome has made its

neighborhood one of the most prosperous in New Orleans; in place of

abandoned warehouses, there are now hotels and office buildings, with

more offices under construction. In its first ten years, the Superdome's

boosters claim, it had a $2.678 billion economic impact on the

community.

So why doesn't every city build one? "It's pretty scary," says Cliff

Wallace, who was general manager of the Superdome for six years and now

runs a publicevents management company in Houston. "Not only do you have

to fork over $150 million to build this thing, you also have to deal with

a significant operating deficit." It's easy to lose money on any stadium,

but much easier when you add in the cost of heating and air-conditioning

and of amortizing a roof.

Being an entertainment machine, rather than a mere sports stadium, adds

to the loss. The Superdome may go from a concert configuration on

Wednesday to basketball on Thursday to football for the weekend to a

trade show on Monday morning. To achieve that flexibility, it runs a

fleet of 98 vehicles: motor scooters, Cushman carts, scrubbers, sweepers,

lift trucks, tractors and "grasshoppers," which pick up and lay down the

artificial turf (known here as Mardi Grass). On its permanent staff, it

employs millwrights, sheet metal workers, carpenters, plumbers,

electricians, refrigeration mechanics, elevator mechanics, a tile setter,

a tile finisher, roofers, painters, sign painters and forklift operators,

among others. All of this contributes to an operating loss of $9 million

a year; about two-thirds of that goes for insurance and a team subsidy.

Retail income versus phantom income

Domes depend on voodoo economics for their survival. Although the

Superdome has operating costs of about $30,000 a day, the Republicans

will get to use the place rent-free for eight weeks this summer because

their convention will have an estimated economic impact of $30 to $40

million. When the Chrysler Corporation once rented the building for only

$10,000 a day, the Superdome turned a profit-on $500,000 in food service.

It is no small trick to balance events that produce real income for the

dome with those that serve civic virtue or produce phantom income in the

community. "You could have the Rolling Stones 20 times a year and make

it," says Wallace, "or a firemen's convention 300 times a year and go

broke."

There aren't all that many entertainment acts capable of filling a

60,000- or 70,000-seat stadium. Rock star Madonna, for instance, did not

sell out at the Astrodome last summer. Domes are thus prone to "dark"

days when nothing happens. To take up the slack, they depend on religious

revivals ("We communed 40,000 people one night," says a Hoosier Dome

official) and silly sports events like Wrestlemania ("We had the largest

crowd ever assembled under one roof," a Silverdome spokesman boasts) or

automotive mud racing ("After a while, nothing seems strange," admits an

Astrodome executive).

A lot of acts, both large and small, try to turn the economic-impact

argument against the domes. In 1984, agents for Michael Jackson likened

his Victory Tour to a Super Bowl, which pays no rent but is said to

generate an income of $100 million or so. They demanded a free ride in

the Superdome and a percentage of the concession and parking fees as

well. (Wallace said no and Jackson went elsewhere.) It has become so bad,

according to Bob Johnson, Wallace's successor, that not long ago one

busload of fans from a competing NFL city tried to use their economic

impact on New Orleans to bargain for better seats at a Saints game.

Bathed in light glaring from on high, colorfully

Bathed in light glaring from on high, colorfully

clad crowd packs the Superdome to enjoy a

football game.

If even the fans are trying to throw their weight around, it's hard to

imagine what the owners of professional teams are up to. Though getting

or keeping a team is usually the main reason cities build a dome, the

team's owner may pay as little rent as $1 a year. "The newer the deal,

the better the deal from the team's point of view," says Wallace. "And

every contract that's renegotiated will be improved in favor of the

team. It has to do with competition among cities, prestige and ego."

Nor does having a dome guarantee that a team will stay put.

The NBA Jazz left the Superdome and the Pistons are pulling out of the

Silverdome to build their own arena. The NFL Oilers threatened to leave

the Astrodome, but decided to remain when stadium authorities agreed to a

$60 million expansion. With more domes being built, the pressure to hold

on to teams by subsidizing them will increase. All this may make civic

leaders reluctant to gamble on a dome.

It will make them reluctant, that is, unless they happened to watch the

Metrodome in Minneapolis "steal" the World Series from the St. Louis

Cardinals last October. The Minnesota Twins won all of their home games

in large part, it is widely believed, because the Metrodome bottled up

and redoubled the roaring of their fans. A dismayed sports columnist in

Milwaukee worried that the first indoor Series was going to give people

the idea that "putting up a weird dome" might be one way to win a

championship. But maybe the uproar over the Metrodome Series was just

another instance of the hype that seems to be the natural element of

domed stadiums everywhere. Before his Bears played the Vikings in the

Metrodome, football coach Mike Ditka remarked sourly: "Indoor domes

should be used for roller rinks" - and then strapped on a pair of skates,

just to make his point.

In truth, all that a dome can really assure is a comfortable outing for

the fans, which is what 20,000 spectators enjoyed on a muggy Thursday

evening last July when Houston took on the Phillies at the Astrodome.

Inside, spotlights illuminated the steel fretwork of the dome, giving it

a 19th-century kind of charm. The crowd was almost subdued, which may

have been partly because of supervision exercised by the Astrodome staff.

("One sign read, 'We hate the Mets worse than Communism,' " recalls a

security man. "We made them take down everything except 'We hate the

Mets.' That's baseball.") Yet dome crowds do appear to be less

rowdy than a typical outdoor crowd. It has to do with the psychology of

being indoors, speculates an Astrodome executive. "My mom always said,

'You want to play, go outside. Don't be rambunctious in the house.' "

It is not a bad insight. Where television brought baseball into the

living room, the domes have brought the living room into the stadium.

Everybody's cool and relaxed. There's a big screen on the scoreboard in

case you missed a call. Freed of the distractions of weather and

rowdiness, a fan in a dome is able to concentrate on the game. That

particular evening in Houston last summer, a kid named Ken Caminiti,

appearing in his first major league game, made some outstanding plays at

third base for the Astros and took a swipe at the doom-dome legend with a

triple and a home run to right field. Baseball was still baseball, the

beer and franks tasted just fine, and after Caminiti walked and scored a

run in the ninth to give the Astros the game, 2 to 1, the crowd went home

happy.

Scheduled to open this spring, multiuse dome in

Scheduled to open this spring, multiuse dome in

Tokyo dwarfs amusement park. It's called the Big Egg.

Back to History Main Menu

Back to History Main Menu

Back to History Main Menu

Back to History Main Menu