Early Years

Early YearsDuring its first year, Colt Stadium, early home of Houston's National League team, sat next to the dome.

Historic construction covers all the basesThe Houston Post, April 9, 1995

To be exact, it was 30 years ago today that the first game was played

indoors, with the Astros beating the New York Yankees 2-1 in an

exhibition game. And a writer craned his neck, took in the sweep of the

roof and the splash of colors and, on these very pages, offered a

prediction: "No team will ever be worthy of this stadium."

Like Milk of Magnesia, that prophecy has stood the test of time. Here it

is three decades later and, sure enough, no Astros team has yet emerged

that might fairly be described as worthy of the roof it dwells under.

No wonder the city of Houston has an Edifice Complex.

To many, the Big Bubble continues to live up to the billing of Judge Roy

Hofheinz, who modestly declared it "the eighth wonder of the world."

Others celebrated, and perhaps less biased observers tended to agree. On

his first visit, the Rev. Billy Graham called the stadium "a tribute to

the boundless imagination of man."

Added Bob Hope: "If they had a maternity ward and a cemetery, you'd

never have to leave."

To begin with, this was the ballpark that made the rain check

obsolete--although an occasional leak in the roof did not do the same

for umbrellas. The thing is, the Astrodome was not just the ultimate

symbol of Texas Tall Talk come true. Given the city's notorious heat and

humidity, it was a necessity, not a luxury.

Rusty Staub made the point by recalling a midsummer series with the

Chicago Cubs, when the team was playing in its temporary, outdoor park.

"You know how Ernie Banks was always saying, 'Great day for two' 'Let's

play two?' Well, we had a doubleheader one afternoon and they had to

carry him off the field on a stretcher."

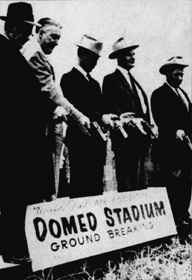

So more than money and vanity went into the building of the planet's first all-weather, multipurpose stadium. After overcoming a tedious series of obstacles --three bond issues and half a dozen lawsuits--construction began in July of 1963. For the ground-breaking ceremonies, instead of shovels a panel of Harris County commissioners fired Colt .45s into the earth, effectively digging up the dirt without the loss of a solitary toe.

Houston's original entry in the National League was named the Colt .45s, honoring the gun that tamed the West. The team became the Astros as part of the city's move into the Space Age--and into its Space Age arena.

Early Years

Early Years

During its first year, Colt Stadium, early home of Houston's National

League team, sat next to the dome.

January 3, 1962

January 3, 1962

Groundbreaking for the Astrodome started with a bang Jan. 3, 1962 as

county commissioners fired Colt .45s with blanks into the ground.

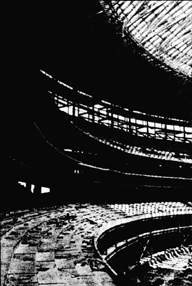

As the months passed, as the steel fingers reached toward the sky, looking like the world's craziest erector set, the fans were entertained by an endless flow of statistics--the miles of wiring and tons of plumbing. The roof, designed by Buckminster Fuller, arched its way to an 18-story peak above second base. It used to be said that the famous Shamrock Hilton hotel would have fit inside the stadium. No one ever figured out a way to test this theory, however, and now the Shamrock is gone.

August 18, 1964

August 18, 1964

Main work on the stadium was complete.

It is easy to forget how strong the skepticism was. Many doubted it

would be built, or would prove suitable for baseball, or would be

completed at anything near the $36 million price tag it carried.

Judge Hofheinz, who conceived the idea of a covered stadium, heard the

complaints and did not suffer them gladly.

"We are building something," he said, "that will set the pattern for the

21st century. It will antiquate every structure of this type in the

world. It will be an Eiffel Tower in its field."

When the Judge described the $2 million scoreboard, you were reminded of

Marryin' Sam in the comic strip Li'l Abner, describing his $5.35

wedding, the one where wild horses are tied to his arms and legs, a

tornado strikes him in the navel and stallions race off in different

directions as he sings "Happy Days are Here Again" in four-part harmony.

There is no point in sniveling now about the scoreboard, which was

dismantled a few years ago to make room for 10,000 more seats. Logic

tells us that there is no point in getting sentimental over a

scoreboard. it is nothing more than wires, fuses, circuits, bulbs, and

transistors. It would be like falling in love with Max Headroom or R2-D2.

Of course millions of us did have a meaningful relationship with The

Great Wall of Houston, over the 23 years that it amused us. Longer than

a football field, funnier than a breadbox, it carried the art form into

the next generation. Bill Veeck had introduced the concept of giving

fireworks with the scores in Chicago, years earlier, but the Astrodome

gave us that and much more: electronic cheerleading. When we referred to

the scoreboard, we really meant the home run spectacular. Whenever a

member of the home team parked a ball in the seats, bulls snorted,

six-guns exploded, a cowboy whirled a lariat, stars danced across the

cosmos and the Texas flag unfurled in tribute.

To compensate for those stretches when the Astros suffered a power

outage, they touched off the board after every home victory. It was the

surest way ever devised to keep the fans in their seats until the end of

a game.

The famed Astrodome

scoreboard

The famed Astrodome

scoreboard

with its snorting bulls, Texas and U.S. flags and

electric cowboys disappeared in 1988 to make room for 10,000 football

end-zone seats.

The Judge hardly missed a trick. He heard that most fans liked to sit behind the dugouts, so he had the architects make them 120 feet long--another record.

The stadium was so special they opened it twice, once with a pre-season game against the Yankees--April 9, 1965--and three nights later, against the Phillies. That week, it was possible to see what the Astrodome really was: a monument to society's war with nature. Catching a fly ball turned into an adventure because the spider web of girders made the ball hard to follow, and in daylight the glare could be blinding. So they finally painted the ceiling--and then the grass died, leading to the birth of something called AstroTurf.

That year, 1965, the Astros peeled off a 10-game winning streak, a success so unexpected that their opponents accused them of tinkering with the air conditioning currents to give the home club an advantage. Bob Aspromonte hit the first indoor home run for the locals, and Willie Mays hit the 500th of his Hall of Fame career.

In one of the season's high spots, the New York Mets came to town and, for the benefit of their television audience, decided that Lindsey Nelson should broadcast the game from the gondola that hangs suspended from the roof. The gondola, which resembles the basket of a hot air balloon, was designed as a photo deck for certain events. It took about 45 minutes to lower and raise the contraption.

Before the game, Nelson and a radio engineer climbed aboard and the

cables hoisted them back toward the ceiling, high above second base, as

the crowd cheered their ascent. It was like a scene from the movie

Around the World in 80 Days.

As the game was about to begin, Casey Stengel, the often outrageous

manager of the Mets, turned to the umpiring crew and said, "What about

my man up there?"

"What man?" asked Tom Corman, the crew chief.

"My man Lindsay up there," he said, pointing, "in that cage under the roof."

All eyes were raised, as if expecting rain. Gorman scratched his head

and decided that since any ball hitting the dome was in play that any

ball hitting Lindsey Nelson should also be in play.

Casey was pleased. "Well," he said, beaming, "my man is a ground rule.

That's the first time my man was ever a ground rule."

Many a rule was broken or rewritten when baseball came in from the rain. And in most years, the Astrodome remained the team's best attraction.

Ten years would pass before another city--New Orleans--dared to build a stadium with a roof on top. The price of that one was estimated at $96 million with cost overruns of at least another $20 million by the time the Superdome opened in 1975. The Judge got his built virtually at cost by assuring his contractors that they would be the experts in the new, growth industry of domed stadiums.

In their first 15 years, the Astros signed some bright and exciting young players who went on to do wonderful deeds. They became All-Stars and played in the World Series--for other teams. The list included Joe Morgan, Rusty Staub, Jimmy Wynn, Jerry Grote, Dave Giusti, Mike Marshall and one or two others too painful to recall.

But the Astros kept trying. They had their share of colorful moments. Larry Dierker threw his first pitch in the majors at 18, and stayed around to start the 1,000th game played in the Astrodome. He celebrated his 12th season in Houston with the first no-hitter of his career, against Montreal.

The Astros had been in the league 10 years before they had a season in which they won more games than they lost. That breakthrough came in 1972, with an 84-69 record. Sensing a shot at the World Series--oh, impossible dream--the Astros changed managers in August, replacing Harry "The Hat" Walker with the legendary Leo Durocher. They finished second.

Managers were easier to find than great players. The Astrodome crowds cheered madly for the likes of Cesar Cedeno, Bob Watson, Jose Cruz, J.R. Richard, Joe Niekro, Glenn Davis and Billy Doran. Injuries ruined the promise of Richard and the gifted Dickie Thon. The fans gave their hearts totally to Nolan Ryan, who pitched his fifth no-hitter in the Astrodome against the Dodgers. But the city still has a case of achy-breaky heart from John McMullen's decision to let Ryan leave, and go on to his final glory with the Texas Rangers.

McMullen's ownership was a turbulent one after he fired Tal Smith as general manager the day after the Astros lost the National League pennant to the Phillies in 1980. Smith, who had been with the club from its pre-Astrodome days, was brought back by Drayton McLane Jr. in 1994, with the title of team president. So Tal is a bridge between the past and a future that the Astros, like every team in baseball, approach with a certain nervousness.

In the '90s, Jeff Bagwell emerged as Houston's franchise player, the best in the league in 1994, a magnificent season that ended in August--one strike and everybody went home.

No one ever doubted that baseball was the primary tenant, but the

Astrodome did indeed serve multiple purposes. Here fans of the Houston

Oilers celebrated the Luv Ya Blue years, and did much of their public

suffering. It was on a Monday night game that the TV camera zoomed in on

a fan sleeping through a onesided loss to the Raiders, when he suddenly

roused himself enough to lift his hand in an obscene gesture.

"It's all right, Howard," Don Meredith assured the modest Howard

Cosell, "he's just saying, 'We're No. 1.' "

In the game many believe put college basketball on the map, Elvin Hayes and the Houston Cougars upset Lew Alcindor and UCLA before 52,000 fans in 1968, and moved into the top spot in the polls.

And, perhaps you may remember these names and moments: Muhammad Ali knocking out Cleveland "Big Cat" Williams in the first heavyweight title bout ever held in Texas; Larry Holmes chopping up Randall "Tex" Cobb in the fight that made Cosell vow never to broadcast boxing again--a high point of Cobb's career.

Then there was Billie Jean King, a woman who wore glasses, beating

55-year-old chauvinist Bobby Riggs in a tennis match dubbed, "The Battle

of the Sexes." The list goes on: bloodless bullfights, soccer, Evel

Knievel on his motorcycle, Karl Wallenda on his tightrope, and even the

premiere of a movie, Brewster McCloud, about a young loner who

lived in the rafters of the Astrodome.

For some of us, it was a case of art imitating life.

For a time, the Astrodome was, in fact as well as symbol, the castle of

Judge Roy Hofheinz. He lived there off and on for several years, in

quarters three stories high, built into the wall 75 feet above right field.

Think of it. For a front yard, he had nearly an acre of lush green AstroTurf.

Judge Roy Hofheinz' apartment

Judge Roy Hofheinz' apartment

included a pool table and a view of the field.

To reach his lodgings, the visitor had to pass the Judge's private

office, guarded by a set of matching six-foot Thai temple dogs, carved

out of solid teakwood and imported from Thailand. His 12-foot desk, with

an inlaid black marble top, featured a gold telephone with 23 extensions

and a view of three TV sets.

One level up was the Judge's home in the Dome. There was a bar, kitchen

and dining room and a bathroom with gold-plated fixtures and velvet

toilet seats. Eight plush easy chairs were arranged in front of the

picture window that overlooked the field.

There was more, oh, so much more: a one-lane bowling alley, a three-hole

putting green, a billiard table (with cast-iron legs made in New Orleans

in 1865), a boardroom with wall-to-ceiling carpet, a right-field patio

with imitation orange trees, a 10-seat movie theater, a barbershop and a

presidential suite with oval scatter rugs bearing the presidential seal.

Lyndon Johnson slept there the night of April 9, 1965. This was where

the Judge slept on other nights.

One tourist described the decor as "Early King Farouk."

Those digs were eliminated during the Dome's remodeling five years ago.

But if walls could talk, what a story you might hear from the one in

right field.

July 30, 1972,

July 30, 1972,

Fans learned what spectators at outdoor stadiums endure: rain. The

source of the strange situation was leaks in the roof. There were no

rain checks but ushers, known as Spacettes, handed out plastic shields.

Back to Astrodome: Published Commentary