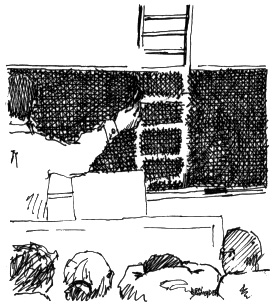

JACOB'S LADDER: MY STRUGGLE UPWARD |

||

| Jonathan Levin Assistant Professor of English |

The Hebrew Bible: my favorite text during the first semester of Lit

Hum, and far and away the hardest for me to teach. I look forward to it,

and I am terrified by the prospect of actually teaching it.

The Hebrew Bible: my favorite text during the first semester of Lit

Hum, and far and away the hardest for me to teach. I look forward to it,

and I am terrified by the prospect of actually teaching it.