|

|

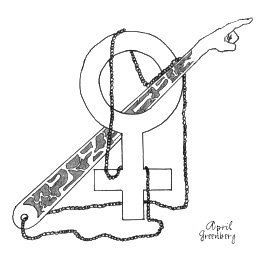

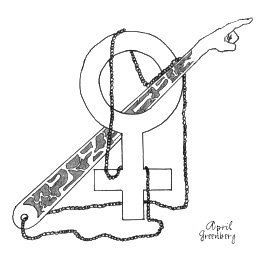

HITTING A BRICK

WALL |

|

Rhoda Seplowitz |

|

Last semester I learned how to chant from the Torah, a skill which had

been taught only to the boys in my Jewish day school class. The

knowledge is useful for any individual interested in Bible study in

Hebrew. Some Biblical commentaries refer to the various notes of Torah

chanting in their explanations of the meaning of certain passages. Now

that I recognize the musical notes of the Torah, I have been able to

follow these Biblical commentaries with greater facility. More

importantly, I now have the skill to read from the Torah at women's

t'fillah (prayer) services.

Last semester I learned how to chant from the Torah, a skill which had

been taught only to the boys in my Jewish day school class. The

knowledge is useful for any individual interested in Bible study in

Hebrew. Some Biblical commentaries refer to the various notes of Torah

chanting in their explanations of the meaning of certain passages. Now

that I recognize the musical notes of the Torah, I have been able to

follow these Biblical commentaries with greater facility. More

importantly, I now have the skill to read from the Torah at women's

t'fillah (prayer) services.

From an early age, I was taught that in the modern world one can do

anything one sets one's mind to--regardless of gender. But every time I

enter an Orthodox synagogue, a different message presents itself. Women

play a very passive role in the traditional service--exclusively because

of their gender and without regard for intellectual capabilities and

achievements. I am not trying to belittle the importance of personal

prayer, as recited by both men and women. But in congregational worship,

there is undoubtedly a crucial element of public participation.

Functions such as reading from the Torah, leading the prayers, and being

called up for an aliyah (to recite a blessing over the Torah), are

distinctions that are never bestowed upon women. In Judaism, I have

repeatedly collided with a brick wall--no matter how much I study my

religion, there is a level of participation beyond which I cannot go.

Now that I understand this dilemma, I must struggle to construct a

resolution within the wide possibilities of society and within the

defined borders of my community.

It was only after my discovery of the women's t'fillah group at

Columbia that I began to perceive the need which it attempts satisfy.

Many of the women who attend women's t'fillah are actually attempting to

address the inequality within the Orthodox community without even

realizing it. One of the reasons women go to these services is to fill

the void that is created by not participating in the Orthodox services.

Of course, this is not the only reason for the existence of women's

t'fillah groups, but it is certainly a good one.

I did not begin to attend women's t'fillah to make a political

statement and I still do not go for that reason. Until college began, I

had essentially prayed at only one type of service: traditional Orthodox.

I am comfortable only at a service in which the traditional prayers are

recited, but I have discovered that there exist less traditional ways to

say those prayers. The atmosphere at the Columbia women's t'fillah

service is comfortable both because it adheres to the traditional service

and because in that service, I never feel like a second class citizen.

The woman's t'fillah group at Columbia follows halakha (Jewish law).

We do not recite those prayers which require a minyan, a group of ten or

more men over the age of thirteen. Because women do not have the same

obligations that men do, they do not count as part of a minyan. Women are

not obligated to pray daily with a congregation. But for this reason,

women's t'fillah sometimes rings hollow to me. Religion requires that

one participate to the extent of one's obligation.

There are certain flaws within halakha, as within any system existing

in an historical continuum. Although I am not willing to violate the

laws that exist, I can certainly express my reservations concerning them.

My dissatisfaction stems from a standard that was developed for men but

not for women. To me, the laws reflect the social norms of the historical

periods in which they were codified. The essence of Jewish law,

religious practice, certainly transcends social norms. On the other hand,

one might argue that the laws were developed in order to fit an implicit

social order within Judaism, to define a woman's true role within a

religious community.

Women's t'fillah avoids, to an extent, the problem of inequality in the

Orthodox communal services, because services for women only are not

communal services. It is necessary that this predicament should not be

regarded solely as a women's issue. In order for women to achieve

equality in religious life, as well as in secular life, men must also be

willing to acknowledge and confront the issues at hand.

I realize that there is a danger in allowing contemporary revision of

the halakha, but there is an even greater danger in stifling religious

participation. If the Jewish community decides that the set role of women

is important enough an issue, the Orthodox rabbinate will concentrate on

this issue, and discuss both the halakhic limits and the halakhic

possibilities.

The question boils down to whether Judaism is an area of life in which

women should seek equality. Will the ideals of equality between the

genders, ideals which are decidedly subjective, prove too great a burden

for the women involved and for the laws which bind them to their faith?

Rhoda Seplowitz is a Barnard College sophomore.

Comments?

Last semester I learned how to chant from the Torah, a skill which had

been taught only to the boys in my Jewish day school class. The

knowledge is useful for any individual interested in Bible study in

Hebrew. Some Biblical commentaries refer to the various notes of Torah

chanting in their explanations of the meaning of certain passages. Now

that I recognize the musical notes of the Torah, I have been able to

follow these Biblical commentaries with greater facility. More

importantly, I now have the skill to read from the Torah at women's

t'fillah (prayer) services.

Last semester I learned how to chant from the Torah, a skill which had

been taught only to the boys in my Jewish day school class. The

knowledge is useful for any individual interested in Bible study in

Hebrew. Some Biblical commentaries refer to the various notes of Torah

chanting in their explanations of the meaning of certain passages. Now

that I recognize the musical notes of the Torah, I have been able to

follow these Biblical commentaries with greater facility. More

importantly, I now have the skill to read from the Torah at women's

t'fillah (prayer) services.