ACTION, NOT ADORNMENT |

||

| Noam Milgrom-Elcott |

I shared a Shabbat dinner earlier this semester with a group of twenty

other Jewish men, talking, eating, singing, and learning. During those few

hours spent together in an East Campus suite, we formed a community, a

community whose goal it was to celebrate Shabbat and improve the larger

Columbia Jewish community. We were all nicely dressed in honor of Shabbat,

and we all wore kippot to signify that we were no ordinary individuals but

members of a Jewish community aimed at Tikkun Olam, the repairing of the

world.

I shared a Shabbat dinner earlier this semester with a group of twenty

other Jewish men, talking, eating, singing, and learning. During those few

hours spent together in an East Campus suite, we formed a community, a

community whose goal it was to celebrate Shabbat and improve the larger

Columbia Jewish community. We were all nicely dressed in honor of Shabbat,

and we all wore kippot to signify that we were no ordinary individuals but

members of a Jewish community aimed at Tikkun Olam, the repairing of the

world.

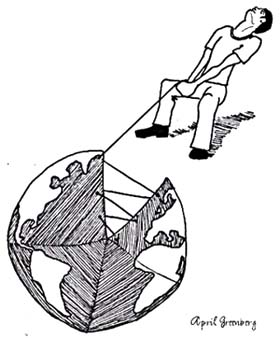

For me, a Jewish man who had worn a kippah for many years, the fact that we were all wearing kippot was especially powerful because, unlike special clothing, whether it be a suit and tie or tallit and t9fillin, a kippah is not limited to certain times and places. Kippah-wearing need not be limited to a particular Friday night, even though our dinner was. Nonetheless, after the dinner I left East Campus, took off my kippah, returned to my dormitory, and completed my evening. Since coming to Columbia, I have stopped wearing a kippah in public. I realize that kippah-wearing can be potentially constructive. Wearing kippot in public now, however, serves to promote exclusivity and social status instead of reminding the wearer of his ties to the entire Jewish people and his obligations to repair the world.

Deciding whether to wear a kippah is a complicated issue--or at least, should be. But before one can fully delve into the quandary of kippah-wearing, a more fundamental issue must be addressed: Tikkun Olam. I believe that the Jewish mission is, above all else, to repair the world, to move toward redemption. Redemption, in turn, can be viewed in accordance with Isaiah9s prophetic vision that universal devotion to the one God will lead to world peace. All Jewish laws and customs must hasten the coming of this redemptive era.Thus, my analysis of kippah-wearing attempts to answer whether kippah-wearing is a constructive or a destructive force in our religious pursuit.

I firmly believe in the potential perfecting power of kippah-wearing. The kippah fulfills two central roles, social and personal. The kippah9s social role is to help create a community, as it did during the aforementioned Shabbat dinner. Communities are the medium through which to best effect change. On the personal level, a kippah facilitates a higher level of awareness of one's actions. There are certain actions that one must or must not perform because he or she is wearing a kippah. For example, the kippah should force a person to think twice before speaking lashon hara, malevolent gossip.

Unfortunately, here at Columbia, the ideal goal of kippah-wearing has been reversed. Kippot have become a regressive, as opposed to an ideally progressive, instrument, and this has been the main reason I stopped wearing a kippah. Instead of creating a community, kippot divide the Jewish community into those who do and those who do not wear them. Within various branches of Judaism, kippot serve as status symbols. A black velvet kippah often signifies a yeshivah bachur while a knitted kippah is associated with a more modern Orthodox or traditional Conservative classification. Instead of unifying the already small kippah-wearing community, kippot act like markers ensuring that each small sub-denomination does not tread on the other9s turf. Even more problematic is the fact that a non-kippah wearing Jew may not feel welcome into a group where all heads are covered, and the reverse is equally true. Furthermore, the Jewish community cannot not afford to separate itself from the general world population. We need to utilize every dollar, every hand, every soul--Jewish or not--to help repair the world. Many of our greatest accomplishments, such as the building of the Temple, operations Moses and Solomon, and the establishment of the State of Israel would have been impossible without non-Jewish help. Unfortunately, the clannishness of kippah-wearing Jews has made kippot virtually synonymous with "Jewish only" in the minds of many non-Jews, and even non-Jewish Columbians. Jewish ideas, programs and events can and must improve more than just the Columbia Jewish community. Kippot, because of their exclusionary character, are one of the chief impediments to non-Jewish involvement in Jewish acts of Tikkun Olam.

Thus far I have been idealistic in my gender qualifications of kippah wearers; it is still not socially acceptable for women at Columbia to wear kippot in public. For the most part, the traditional community would not hear of "allowing" women to wear kippot, though it has nothing to do with Jewish law. Kippah-wearing is a custom and a default action on the part of the traditional community that upholds a status quo and isolates half of its ranks. Because the traditional community has set the standard for the entire Jewish population (not to the credit of the egalitarian community), even those women that would like to wear kippot in public are held back from doing so. Thus, kippot act to divide men from women, severing, instead of building, a community.

The distinctly personal role of kippot forces one to be aware of his or

her actions. While wearing a kippah, one should hesitate to use profanity,

feel obligated to give money to a passing homeless person, and pay closer

attention to the myriad mitzvot that are easily forgotten. More often

than not, kippot are worn while sharing earfuls of lashon hara and

passing hungry beggars. They are worn during prayerless mornings and while

performing numerous other infractions of Jewish law and ethical standards.

Kippot seem to promote social standards only, not Torah standards.

For those who always wear the kippah, the kippah has become so mundane

that I am skeptical it affects behavior at all. I give the same amount to

the homeless as I did when I wore a kippah, and I speak as much lashon

hara. I see few behavioral differences between the kippah-wearing and

non-kippah-wearing communities in terms of the social and personal roles.

A kippah, as a custom, is a social phenomenon and must be addressed in the

social realm. The kippah-wearing community must make a conscious choice as

a community. Preserving the status quo, oblivious to the many deficiencies

kippah-wearing has now accrued, will render kippot progressively more

divisive and less meaningful, impeding the Jewish mission of repairing the

world. On the other hand, kippot have immense potential, potential that we

are presently not unleashing. By consciously utilizing kippot to remind us

of our never ending mission to repair the world, not to exclude 3other2

denominations of Judaism, women, and non-Jews, wearing a kippah can once

again be a powerful force in Judaism. As the kippah reminds us, there are

no default decisions. Every action must be precise and conscious. Let9s

start taking our kippot seriously so that we can get to the more serious

business of repairing the world.