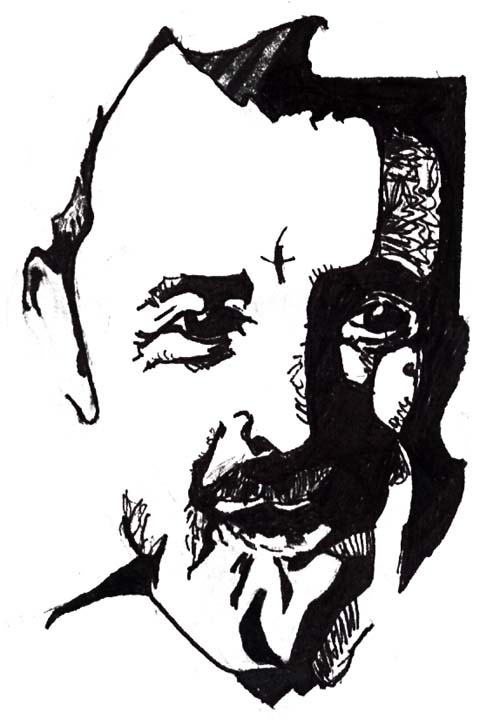

INTERVIEW: DAVID WEISS HALIVNI |

||

| Deena Aranoff |

Professor David Weiss Halivni experiences life with a keen

awareness of the contradictions within it. He is caught by no illusions of

the grandeur of humanity, nor does he have a deep faith in the potential

for progress. The darkness he has witnessed in addition to the splintering

power of his mind has shorn away the optimism of ignorance.

Professor David Weiss Halivni experiences life with a keen

awareness of the contradictions within it. He is caught by no illusions of

the grandeur of humanity, nor does he have a deep faith in the potential

for progress. The darkness he has witnessed in addition to the splintering

power of his mind has shorn away the optimism of ignorance.

Yet there is a calm spirit in his eyes which leads one to believe that his recognition of the contradictions in life has not preempted the reconciliation which makes living possible. His commitment to Jewish learning and his faith in the integrity of Jewish law have formed a bridge over waters made murky by events he has witnessed or suffered. His success in applying modern scholarship to the study of Talmud signifies a rare reconciliation which has brought scores of students to him for help in grappling with the challenge modernity poses to tradition. I approached this interview with similar optimism, expecting Professor Halivni to present a position which allows Torah study and tragedy, modern morality and sacred tradition, to coexist. Instead he argued that there are tolerated contradictions, some of which can be eased with time and others which will permanently clash.

DA: In your memoir, The Book and the Sword, you express the tension

of

learning in the face of destruction. You state that you did not continue

your formal learning until months after liberation, implying that the very

existence of the Nazi evil prevented the endeavor. Yet your stories from

the camps are full of Torah study, describing it as a source of security

and comfort.

DWH: So you have a contradiction, that's exactly what life is. My

memoir

represents a new type of writing memoirs: instead of including the

grizzliness and the details of what happened, I write only how I as an

individual survived. Yet the story of the individual, the story itself,

contains a contradiction! Why does one survive and the others do not? It's

not true that those who survived had to do something immoral or anything

superhuman. There are cases like that, of course. But the overwhelming

majority of those who escaped just survived. They were physically

stronger, or the circumstances were more favorable. So there is basically

a contradiction. But the point here is that in my case, since each

individual is different, it was learning that was essential. In the book I

refer to the Kapo who used to pump me for erotic material in the Talmud.

We were too weak to have sexual desires, but the Kapo had what to eat, and

therefore had sexual desires. The Kapo later saved me from a selection

that would probably have meant death.

DA: And so you studied despite the war, despite the

contradiction?

DWH: Contradiction describes it! The only way to describe it is

through

contradiction. That is why you cannot ask why of the Holocaust. When you

ask why in this particular situation, you mitigate the uniqueness. The

only thing that I can find parallel is revelation, which is a mystery. God

broke into history! For the believer it is there, it is a unique act. It's

the same question. This too is a unique act.

DA: As a student of history, one of the issues that I often think

about is

whether or not there is uniqueness in history.

DWH: I deny its existence, except in this situation.

DA: But couldn't you peel away all the reasons why people survived

and end

up with principles which could explain survival? The study of survival is

beyond scholarship only because it is impossible to study each individual,

not because the survival itself is inexplicable.

DWH: Even if you study each individual, the parts will not add up

to the

whole. It has to be unique! Think of the two million children! If it is

not unique, then you must explain it, implying that we could have expected

it had we known the facts. But such magnitude-- it was a unique moment in

history.

DA: In your book I sense an awareness of God's presence at the same

time

as an awareness of God's hester panim (or, turning his face away). How can

the importance of having t'fillin in the camps, or the decision to risk

death for the sake of obtaining a bletl (small piece of Jewish text)

coexist with this awareness of the absence of God?

DWH: You are trying, and that is natural in young people, and old

people,

to make sense of it. The purpose of the book is to show that it doesn't

make sense. It's riddled with contradiction. If it weren't so, it would

not be unique. It would be a bigger act, a larger act, but to be unique

means that when we explain, it defies. For young people it is difficult,

they are anxious to bring order and simplicity. As you get older, life is

not simple. And very often the order is nothing but a falsification. To

bring an analogy, part of the attraction of Communism and Marxism is that

things fit in...you could almost define a human being through knowledge of

how much money he has in the bank. When I asked him why he rejected

socialism, the late Moshe Meisels, one of the few Jewish intellectuals who

was not a communist or a socialist, responded, "it is because it reduces

man to great simplicity."

DA: Isn't simplicity one of the driving forces behind your

scholarship?

DWH: Scholarship, yes! I can only decide the interpretation of one

text

over another because one is more simple. But life isn't simple.

DA: And that's okay?

DWH: Okay, not okay! That's the way it is. Reason is good, it is

indispensable, you cannot live life without it. But man is not exhausted

by it. And when you have these extraordinary times, irrationality is

catapulted and becomes the dominating force. My memoir tries to explain

how an individual survived in the midst of this madness, not explaining

the madness that it should not be madness. That may be the task of the

historian, of whom I plead to withhold his profession and try not to

explain the holocaust. But at least I am trying not to explain the madness

away that it's not madness. I'm just explaining how I navigated in the

midst of the madness. The madness is there. To understand this event,

reason is impotent.

DA: And what is the function of learning?

DWH: The appeal of learning has nothing to do with what you learn.

Who

cares, basically, whether you learn Talmud or not? What part of life does

it correspond to? But you make it important, you make it crucial. It's the

continuity of generations, it's an intellectual activity in which you

create yourself in an artificial way. Like art, learning is a way of

extending yourself, and of extending reality.

DA: In your book you say that a religious Jew, when faced with a

confrontation between sociology and religion, must choose religion. Yet,

do we not accept that humanity has progressed in its moral capabilities?

And if so, how can we justify regressing towards a more ancient standard

of morality when such a conflict arises?

DWH: On the surface, of course we feel progress. People are

protected,

people have a certain security, there is international law. But just wait

until something goes a little wrong. Serbia is an example. They are

crueler than ever. It's a thin veneer of moral progress. Yet it is true

that morality has progressed somewhat. But you still have to take into

consideration what halakha, what religion, means and how easily religion

could be overthrown. If you put it that starkly, that when modernity

conflicts with halakha, the halakha must recede, then you undermine it. If

young people come to me and tell me that they are in love and want to

intermarry, there is nothing I can do, other than tell them that it is

against the halakha. There is a certain integrity that needs to be kept,

otherwise it caves in. We are an old people, we have a certain allegiance.

We shouldn't take hasty steps that undermine it. As a result, in the issue

of women is the contemporary community, I draw the line. The rabbinate,

no. Learning, yes.

DA: How will women's learning bring change without the potential to

be in

positions of power?

DWH: The power rests in learning.

DA: I would like to discuss your thoughts on the halakhic process

of

change. In your book you say that changes did take place in an older age,

but they were not done consciously. The changes were integrated into

community life long before they sought--and received--legal sanction. Is

this type of change possible today?

DWH: In the small communities of the past, reform could be

isolated,

cordoned off, with little or no impact on the other laws or on the system

as a whole. They had no doubts about the text, about the divine giving, so

the effects of change could be localized. Today, on the other hand, any

change in response to modernity is another nail in the coffin which denies

the very idea of revelation. However, you can bring yourself to a position

where you can change.

DA: But does this unprecedented awareness of the historical process

of

halakhic change make almost any change impossible?

DWH: Modern intellectual living and the accompanying historical

awareness,

on the one hand, is a blessing. On the other hand, it makes every change

larger, more difficult, and slowed down.

DA: Change is possible?

DWH: Yes. We can bring ourselves to change. It is a matter of

degree.

Things are changing all the time, but change cannot be an overt concession

to modernity. Viewing us a century from now, the historian may describe it

as such, but we don't have to make that decision in our minds.

I sat with two people when I sat with Professor David Weiss Halivni.

I

sat with a man of faith in reason and a man of faith in madness. He

embodies the reconciliation of worlds as well as the contradiction between

them. The only element of his world rescued from the haunting echo of

contradiction is his belief in the necessity of Torah study. Learning

escapes the challenge of present contradiction because it makes no attempt

to settle ambiguities, nor does it attempt to make sense of clashing

realities. Study provides the opportunity for intellectual activity, the

security of continuity, and therefore the survival of the individual as he

or she navigates through the madness of human experience.