Designed by Max Rosenthal

PHILADELPHIA: The American City

AN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE SKETCH BY TALCOTT WILLIAMS

Philadelphia was the first of American cities to reach the permanent charac¬

ter which it was to keep for all time. For cities, like men, have their youth and

their maturity, their temperament and their character, their careers and their

destiny, their triumphs and their failings, those who hate and those who love.

There has been no moment for 3,000 years when Damascus has not been rapt

among its waters and sat in its tender green. The Roman camp about which

the Parisi gathered differed no whit in the letters of Julian a millennium and

a half ago from Paris in the letters of Balzac. There has been no moment for

3,000 years when Singan-fu has not held its solitary state in its narrow, walling

mountain, a city of dignities and ranked palaces, be they empty, as for centuries

past, or full, as in the last twelvemonth.

Our American cities come but late to their historic right. No one confounds

the Boston of Faneuil Hall and the Common with the Boston of the Public

Library and of open squares, thronged streets and brilliant and builded ways.

The New York of Wall Street and the Battery is not the imperial city which

queens it over a harbor full of gathered boroughs. Even in Chicago, they

draw their sharp line between the city "before the fire," frame, low, squalid, and

the growing splendors which have piled the business town of the modern Babel

on the trembling morass. These all change. Philadelphia remains stanch and

American from its start, through all its spreading thousands between the rivers

and beyond.

This city had no frontier youth. It had won its charter twenty years after

the first house had been built on its city site and the gap between the first

Swede settlement and a Mayor and Burgesses dealing with all city evils was

briefer than for any other of our Atlantic municipalities. It grew like a mush¬

room, 2,500 houses in a score of years. No other colonial city saw the like.

The thin line of gabled houses, perched on the steep river bank in 1720, up

which Franklin climbed a few years later, had bloomed into towers and steeples,

the State House and Christ Church, the square residences of South England

and the double-gabled roofs of the Palatinate before he had reached middle life.

Its very colonial days alone of our early cities drew together all the fore¬

runners of national greatness. It had at its western gate the wheat-fields of

Lancaster and first sent out corn to feed other lands. On its very soil the pine

and oak, cypress and chestnut met, and on the Delaware began the larger

American shipbuilding on sites where the greater yards of the future were to

launch the warships of Czar and Mikado with the serried fleets of the Republic.

It had its Germantown when all the other colonies were English and insular,

and all the arts of Central Europe were brought here by the artificers of the

Rhine. Here tanning began, and here shoes were earliest made for more than

local use, the wool trade began here and here the lesser arts of life. Here beer

was first brewed, here the printing-press began in more than one tongue. Iron

was first made about it, and arms and the Conestoga wagon—the wain of Central

Europe—began Western trade and prefigured the Philadelphia locomotive, whose

voice has gone through the earth and the sound thereof, from the Southern to

the Northern seas.

When the Revolution came the city was compact of all the strands of later

national life. Foreign tongues were spoken in its streets and the stream of its

life was enriched by German and Moravian, by Huguenot and by Spanish Jew,

the long-lineaged aristocrat of his race, whose descent makes all other seem

of yesterday. It was the natural center of the colonies, the keystone of their

arch. Here were the great bankers, Morris and the rest. In their banking

parlors the debts of the infant Republic were funded, for European financiers

knew no other American credits. Its State House was the one imposing

secular building of the Thirteen Colonies, and it remains ni^h two centuries

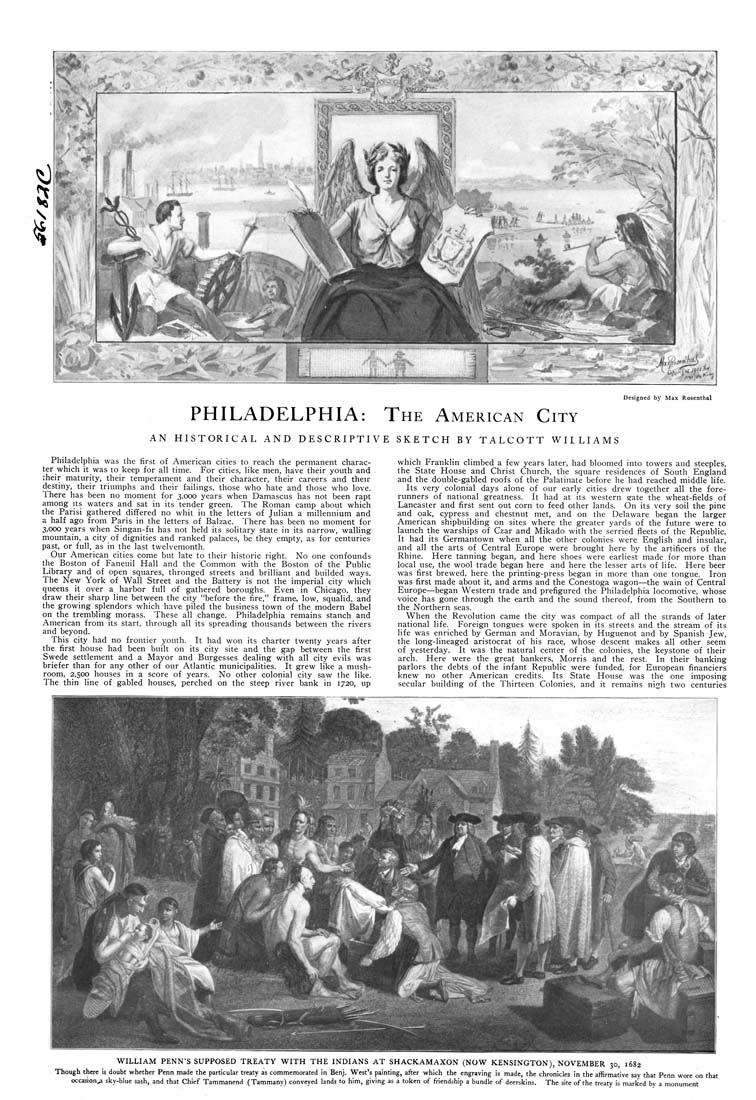

WILLIAM PENN'S SUPPOSED TREATY WITH THE INDIANS AT SHACKAMAXON (NOW KENSINGTON), NOVEMBER 30 1682

Though there is doubt whether Penn made the particular treaty as commemorated in Benj. West's painting, after which the engraving is made, the chronicles in the affirmative say that Penn wore on that

occasion^ sky-blue sash, and that Chief Tammanend (Tammany) conveyed lands to him, giving as a token of friendship a bundle of deerskins. The site of the treaty is marked bv a monument

|