AMERICAN DICTIONARY

OF

Printing and Bookmaking.

THE first letter in almost all lan¬

guages, is one of those most com¬

monly used. In English only two

letters exceed it in frequency. In

the case it is nearest to the right

hand. In job fonts it is taken as

the measure of their magnitude, as

4A, 5A, lOA, meaning that num¬

ber of letters which would require

four, five or ten capital A's to be

in due proportion to the rest of the font. This also

occurs as 3A, 6a, meaning the proportion of lower-case

and capital letters. It is the first signature in a book,

but its mark is nearly always suppressed, as the let¬

ter would come at the foot of the title-page and would

be unsightly. In a daily newspaper office, where the

articles are numbered by letters, the one marked A is

the first to go out when composition begins, the takes

being numbered la, 2a, 3a and so on. There are a great

variety of accents to A. As the mark of the passive

participle in English of the last century and earlier it

takes a hyphen after it, as a-building, a-riding, a-going,

but when it is a preposition, as in afoot, asleep, it unites

with the succeeding word. In form the small a is one

of the most irregular of all letters. Among the Greeks

a stood for 1, but with the Romans for 500. A is the

sixth note of the natural scale, and a denotes the same

interval in the second octave. With a line above a

shows the same in the next octave still, and with two

lines in the second octave. To distinguish them they

are known as the one-lined octave, two-lined octave, and

so on. In music a figure prefixed to a vocal composi¬

tion indicates the number of voices it is intended for, as

A3, where three voices are needed. A enters into many

abbreviations. With a line around it, @, it is known as

commercial a, and signifies to or at, generally the former

in American offices.

Abattre la Garniture (Fr.).

the furniture.

Abbassamento del Timpano (Ital.).

frisket.

Abbildung- (Ger.).—A cut, delineation or picture.

Abbonati (Ital.).—Subscribers to a newspaper.

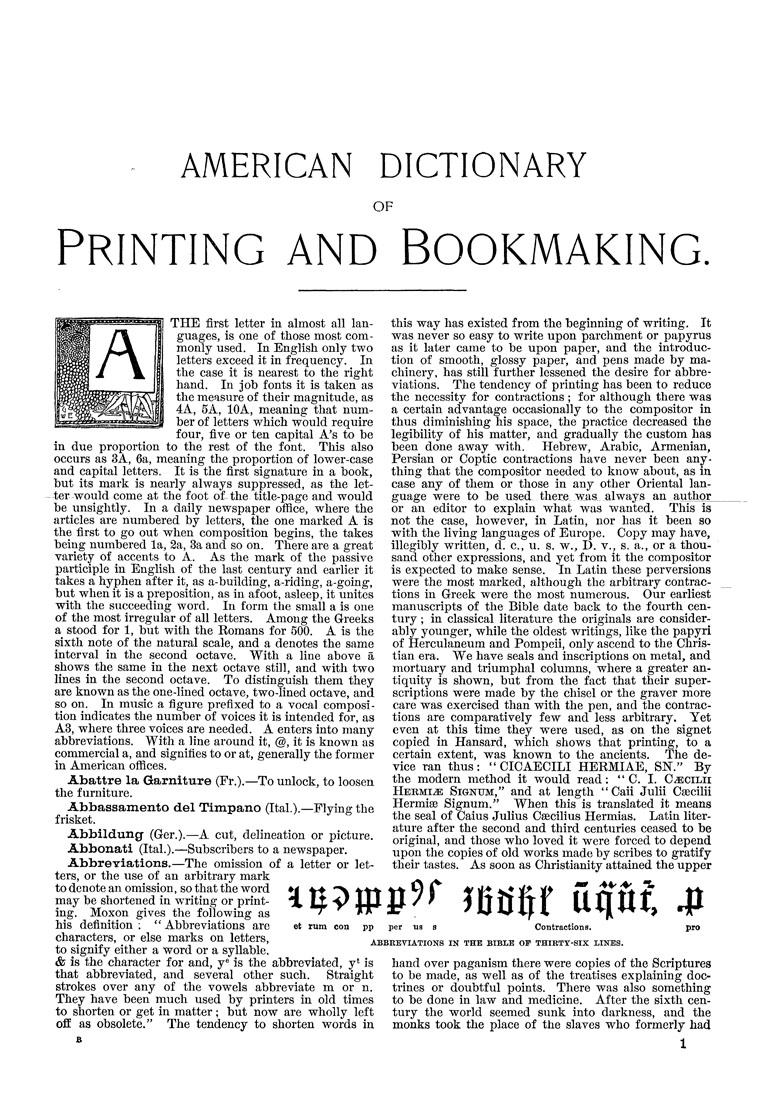

AbbreYiations.—The omission of a letter or let¬

ters, or the use of an arbitrary mark

to denote an omission, so that the word

may be shortened in waiting or print¬

ing. Moxon gives the following as

his definition ; '' Abbreviations are

characters, or else marks on letters,

to signify either a word or a syllable.

& is the character for and, y^ is the abbreviated, y* is

that abbreviated, and several other such. Straight

strokes over any of the vowels abbreviate m or n.

They have been much used by printers in old times

to shorten or get in matter; but now are wholly left

off as obsolete." The tendency to shorten words in

this way has existed from the beginning of writing. It

was never so easy to write upon parchment or papyrus

as it later came to be upon paper, and the introduc¬

tion of smooth, glossy paper, and pens made by ma¬

chinery, has still further lessened the desire for abbre¬

viations. The tendency of printing has been to reduce

the necessity for contractions ; for although there was

a certain advantage occasionally to the compositor in

thus diminishing his space, the practice decreased the

legibility of his matter, and gradually the custom has

been done away with. Hebrew, Arabic, Armenian,

Persian or Coptic contractions have never been any¬

thing that the compositor needed to know about, as in

case any of them or those in any other Oriental lan¬

guage were to be used there was always an author

or an editor to explain what was wanted. This is

not the case, however, in Latin, nor has it been so

with the living languages of Europe. Copy may have,

illegibly written, d. c, u. s. w., D. v., s. a., or a thou¬

sand other expressions, and yet from it the compositor

is expected to make sense. In Latin these perversions

were the most marked, although the arbitrary contrac¬

tions in Greek were the most numerous. Our earliest

manuscripts of the Bible date back to the fourth cen¬

tury ; in classical literature the originals are consider¬

ably younger, while the oldest writings, like the papyri

of Herculaneum and Pompeii, only ascend to the Chris¬

tian era. We have seals and inscriptions on metal, and

mortuary and triumphal columns, where a greater an¬

tiquity is shown, but from the fact that their super¬

scriptions were made by the chisel or the graver more

care was exercised than with the pen, and the contrac¬

tions are comparatively few and less arbitrary. Yet

even at this time they were used, as on the signet

copied in Hansard, which shows that printing, to a

certain extent, was known to the ancients. The de¬

vice ran thus: " CICAECILI HERMIAE, SN." By

the modern method it would read: *'C. I. Cecilii

Hermit Signum," and at length "Caii Julii Csecilii

Hermise Signum." When this is translated it means

the seal of Caius Julius Csecilius Hermias. Latin liter¬

ature after the second and third centuries ceased to be

original, and those who loved it were forced to depend

upon the copies of old works made by scribes to gratify

their tastes. As soon as Christianity attained the upper

-To unlock, to loosen

-Flying the

et rum con pp per us s

Contractions.

ABBKEVIATIONS IN THE BIBLE OF THIRTY-SIX LINES.

hand over paganism there were copies of the Scriptures

to be made, as well as of the treatises explaining doc¬

trines or doubtful points. There was also something

to be done in law and medicine. After the sixth cen¬

tury the world seemed sunk into darkness, and the

monks took the place of the slaves who formerly had

1

|