GER

AMERICAN DICTIONARY OF

schehe auf Erden wie im Himmel. Unser taglich Brot

gib uns heute, und vergib uns unsere Schulden, wie wir

unsern Schuldigern vergeben; und f iihre uns nicht in

Versuchung, sondern erlose uns von dem Uebel. Denn

dein ist das Reich und die Kraft und die Herrlichkeit in

Ewigkeit. Amen.

The study of German is not very difficult. Nine-tenths

of all of our common words are to be found in that lan¬

guage, although disguised ; its accent resembles ours, and

although there are some difficult sounds they are acquired

after a little, and can then always be distinguished by the

ear. The spelling of German is regular and is unattended

with such curious combinations as are found in English

and French. The language of common people is quickly

learned; but that of science, literature and history has

many words which cannot be understood even by know¬

ing the elements. Thus while St. Mark can be under¬

stood in most places after a few weeks of study, the same

time devoted to the Epistle to the Hebrews would pro¬

duce very little results. Acquisition of German is best

made in books on 011endorft''s plan, then followed by

grammars on the old method, continually supplemented

by outside reading and by conversation with Germans.

A good plan is to learn extracts from good authors by

heart. The most common small English and German dic¬

tionary found here is Oehlenschlager's ; larger dictiona¬

ries are Adler's and Grieb's. A valuable large German

work is Grimm's Worterbuch, and there are many others.

The orthography of German has altered considerably

since the invention of printing. One difficulty which the

language has always had is in distinguishing the lighter

from the heavier labials, an uncertainty which still pre¬

vails in speech, although the spelling has been fixed by

usage. Thus the final consonant in und, and, is pro¬

nounced as a t; bleiben, to stay or to remain, might be

pronounced bleipen anywhere in Germany without ex¬

citing remark; and it is well known how difficult it is

for the German in America to say take instead of dake.

Where there was doubt, usage has sanctioned one form.

For instance, in a book published in 1572 Truckerei is

used, instead of Druckerei. The latest change before the

middle of this century was that of y to i in such words as

seyn, but of late the silent h has been dropped by many

printers in words like Tlieil. This usage is not uniform.

German, Printing in.—The chief fact which

strikes those who attempt to read a German book or to

study German typography is that the characters are in

black-letter, or in that style which was used by copyists

in Germany before the invention of printing. These

have been slightly modified, but at no time has the popu¬

lar taste inclined towards the shape of the letters used in

England, Holland, France and the countries in the South

of Europe, The German character is called at home

Fraktur, or broken ; and the Roman letters are known

as Antiqua, or old. In speaking of the alphabets the

latter is called the Latin, and the characters Latin letters.

The German alphabet has the same number of letters as

English, excepting that in the Fraktur I and J have the

same letter as a capital. When type is set in Roman a

distinction between the two is made. The letters are as

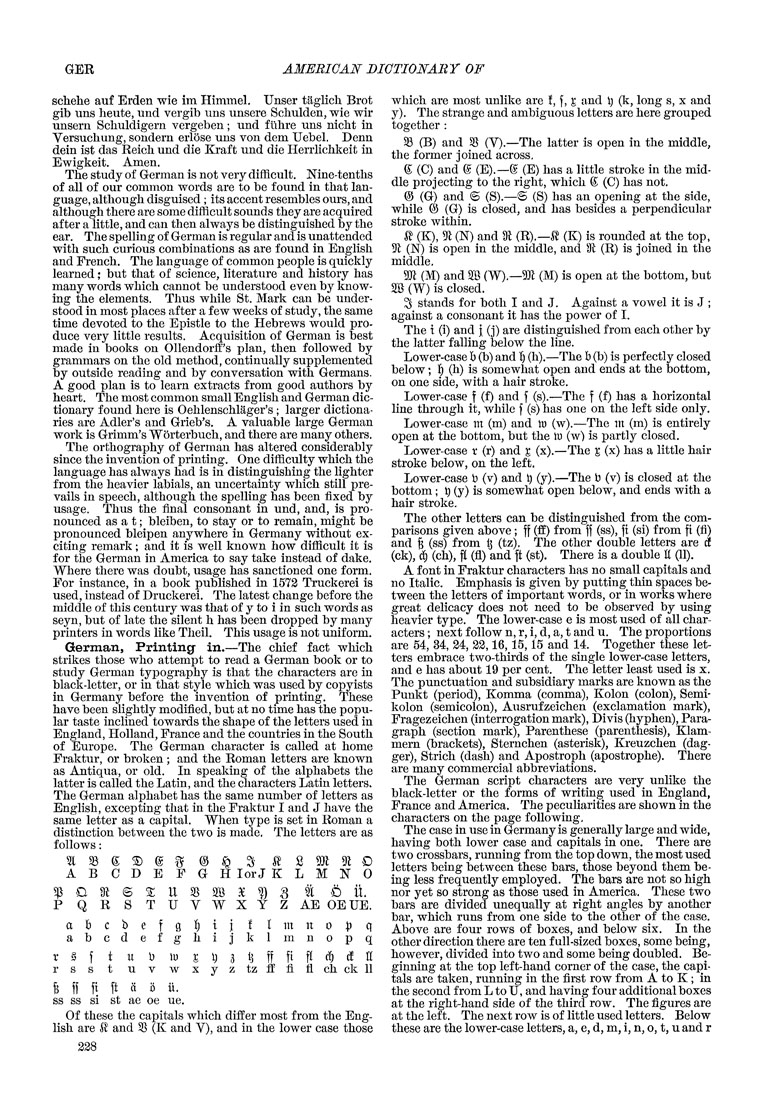

follows:

ABCDEFGH lor J K L M N 0

^C9^©^U353B3e?)3 ft Oil.

P Q R S T U V W X Y Z AE OEUE,

a b c b e f g 1^ i } ! I m n o |) q

abcdefghijklmnopq

r g f t u b lu ^ I) a 13 ff fi ft <^ ^ n

r s s t u V w X y z tz ff fi fl ch ck 11

§ ff ft ft ci 0 ii.

ss ss si st ae oe ue.

Of these the capitals which differ most from the Eng¬

lish are ^ and 35 (K and V), and in the lower case those

which are most unlike are !, f, l and I) (k, long s, x and

y). The strange and ambiguous letters are here grouped

together :

33 (B) and 35 (V).—The latter is open in the middle,

the former joined across,

^ (C) and (g (E),—(^ (E) has a little stroke in the mid¬

dle projecting to the right, which (^ (C) has not.

% (G) and © (S).—© (S) has an opening at the side,

while (^ (G) is closed, and has besides a perpendicular

stroke within.

^ (K), 5^ (N) and 9^ (R).—.^ (K) is rounded at the top,

5fl (N) is open in the middle, and 91 (R) is joined in the

middle.

m (M) and B (W).—9Jl (M) is open at the bottom, but

SB (W) is closed.

^ stands for both I and J. Against a vowel it is J ;

against a consonant it has the power of I.

The t (i) and j (j) are distinguished from each other by

the latter falling below the line.

Lower-case b (b) and !) (h).—The b (b) is perfectly closed

below; 1^ (h) is somewhat open and ends at the bottom,

on one side, with a hair stroke.

Lower-case f (f) and f (s).—The f (f) has a horizontal

line through it, while f (s) has one on the left side only.

Lower-case m (m) and in (w).—The m (m) is entirely

open at the bottom, but the in (w) is partly closed.

Lower-case r (r) and x (x).—The % (x) has a little hair

stroke below, on the left.

Lower-case b (v) and t) (y).—The b (v) is closed at the

bottom; ^ (y) is somewhat open below, and ends with a

hair stroke .

The other letters can be distinguished from the com¬

parisons given above; ff (ff) from ff (ss), ft (si) from ft (fi)

and § (ss) from tj (tz). The other double letters are d

(ck), ^ (ch), ft (fl) and ft (st). There is a double It (11).

A font in Fraktur characters has no small capitals and

no Italic. Emphasis is given by putting thin spaces be¬

tween the letters of important words, or in works where

great delicacy does not need to be observed by using

heavier type. The lower-case e is most used of all char¬

acters ; next follow n, r, i, d, a, t and u. The proportions

are 54, 34, 24, 22,16,15,15 and 14. Together these let¬

ters embrace tv/o-thirds of the single lower-case letters,

and e has about 19 per cent. The letter least used is x.

The punctuation and subsidiary marks are known as the

Punkt (period), Komma (comma), Kolon (colon), Semi-

kolon (semicolon), Ausrufzeichen (exclamation mark),

Fragezeichen (interrogation mark), Divis (hyphen). Para¬

graph (section mark), Parenthese (parenthesis), Klam-

mern (brackets), Sternchen (asterisk), Kreuzchen (dag¬

ger), Strich (dash) and Apostroph (apostrophe). There

are many commercial abbreviations.

The German script characters are very unlike the

black-letter or the forms of writing used in England,

France and America. The peculiarities are shown in the

characters on the page following.

The case in use in Germany is generally large and wide,

having both lower case and capitals in one. There are

two crossbars, running from the top down, the most used

letters being between these bars, those beyond them be¬

ing less frequently employed. The bars are not so high

nor yet so strong as those used in America. These two

bars are divided unequally at right angles by another

bar, which runs from one side to the other of the case.

Above are four rows of boxes, and below six. In the

other direction there are ten full-sized boxes, some being,

however, divided into two and some being doubled. Be¬

ginning at the top left-hand corner of the case, the capi¬

tals are taken, running in the first row from A to K ; in

the second from L to U, and having four additional boxes

at the right-hand side of the third row. The figures are

at the left. The next row is of little used letters. Below

these are the lower-case letters, a, e, d, m, i, n, o, t, u and r

|