PRINTING AND BOOKMAKING.

GER

imagine because he sometimes sees these marks over the

top of a word and sometimes does not see them that the

one or the other is wrong. They may both be right, in

difCerent places. It is also permissible in jobs, inscrip¬

tions, capital lines and other places where there is plenty

of room to spell out these compound letters. Some

proper names, as Goethe, are always written in full, yet

in his lifetime his name was frequently printed as Gotlie.

A general practice is to use letters and figures of the

ordinary size, in Italic, for references to notes, accom¬

panied by one parenthesis, as a). Roman is also used in

tlie same way.

Folio headings of books printed in Fraktur are usually

in type hke the text; headings to sections, or subdivi¬

sions of headings, in iyi^Q slightly larger and blacker than

the text.

Quotations of words or sentences are indicated by two

sharp-pointed commas before the bottom of the letter

where the quotation begins, and the same upside down

where it ends, as „^Ku§fc5^ieJ3en." The same usage is ob¬

served in Roman characters, as ,,Die Knnst zii sterben."

Apostrophes are not used for this purpose.

The Gei-man marks of correction are much like those

in English. Bad and wrong letters are indicated by

writing the riglit letter in the margin. Paragrapiis are

shown by a bracket marked in. The dele or take-out

mark is the same as in English, but resembling the Ger¬

man form of d more than ours. A doublet is known as

a Hochzeit, or wedding. Tiie space mark in English

(fl) is employed in German to indicate a high space, a lead

being up, or a rectification of spacing. As there is no

Italic, and emphasis is indicated by thin spacing em¬

phatic words, a special mark is contrived for this, which

is a straight line with a number of inclined strokes cross¬

ing it. To show that durchschossene Worter, as these

are described, should be altered back, a wave line is used

in the margin. A word which cannot be decipliered, or

for which there nre no sorts, is shown, as in English, with

the feet at the top and the heads down. Crooked lines

have parallel straight lines drawn against them, above

and below. Run-in paragraphs arc marked by a line

drawn from the end of one paragraph to the beginning

of the next.

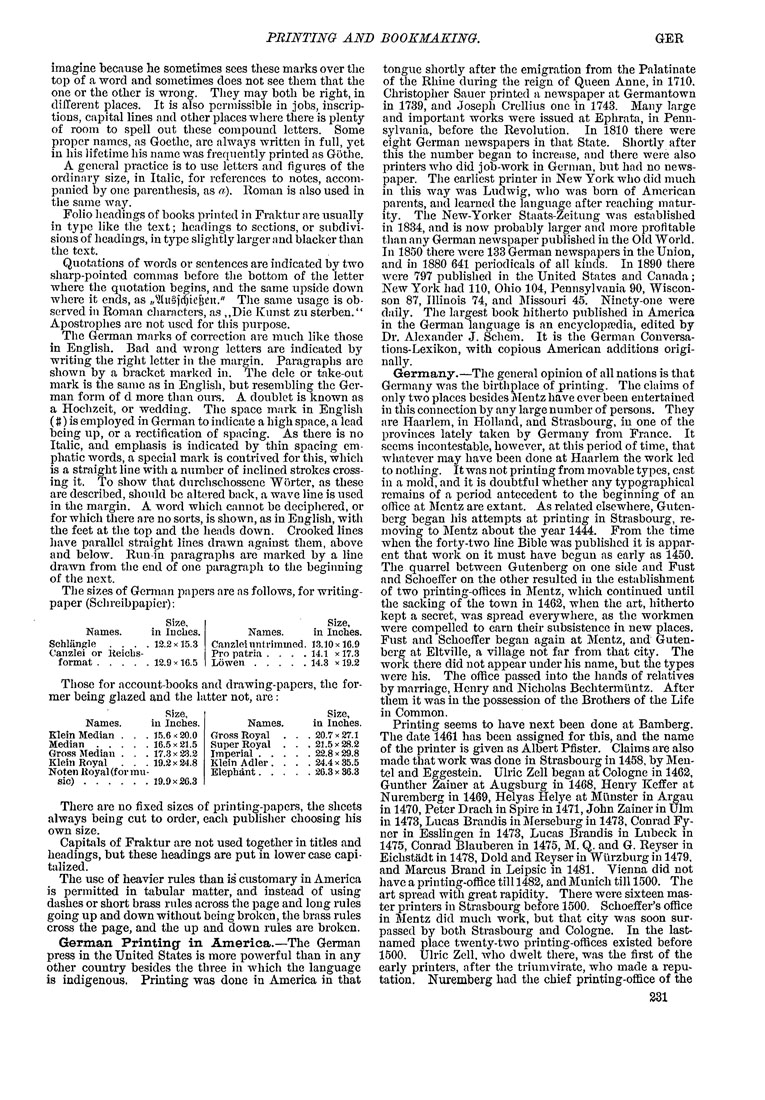

The sizes of German papers are as follows, for writing-

paper (Schreibpapier):

Size,

Names. in Inches.

Names.

Size,

in Inches.

Schlangle .... 12.2x15.3

Canzlei or Reichs-

format.....12.9x10.5

Canzlei untrimmed.

Pro patria . . . .

Lowen.....

13.10x16.9

14.1 xl7.3

14.3 xl9.2

Those for account-books i

mer being glazed and the lu

md drawing-papei

Ltter not, are:

s, the for-

Size,

Names. in Inches.

Names.

Size,

in Inches.

Klein Median . . . 15.6 ^ 20.0

Median.....16.5x21.5

Gross Median . . . 17.3x23.3

Klein Royal . . . 19.2x34.8

No ten Royal (for mu -

sic)......19.9x26.3

Gross Royal . .

Super Royal . .

Imperial ....

Klein Adler. . .

Elephant....

. 20.7x27.1

. 23.5x28.2

. 22.8x29.8

. 24.4x35.5

. 20.3x36,3

There are no fixed sizes of printing-papers, the sheets

always being cut to order, each publisher choosing his

own size.

Capitals of Fraktur are not used together in titles and

headings, but these headings are put in lowercase capi¬

talized.

The use of heavier rules than is customary in America

is permitted in tabular matter, and instead of using

dashes or short brass rules across the page and long rules

going up and down without being broken, the brass rules

cross the page, and the up and down rules are broken.

German Printing in America.—The German

press in the United States is more powerful than in any

other country besides the three in which the language

is indigenous. Printing was done in America in that

tongue shortly after the emigration from the Palatinate

of the Rhine during the reign of Queen Anne, in 1710.

Christopher Sauer printed a newspaper at Germantown

in 1739, and Joseph Crellius one in 1743. Many large

and important works were issued at Ephrata, in Penn¬

sylvania, before the Revolution. In 1810 there were

eight German newspapers in that State. Shortly after

this the number began to increase, and there were also

printers who did job-work in German, but had no news¬

paper. The earliest printer in New York who did much

in this way was Ludwig, who was born of American

parents, and learned the language after reaching matur¬

ity. The New-Yorker Staats-Zeitung was established

in 1834, and is now probably larger and more profitable

than any German newspaper published in the Old World.

In 1850 there were 133 German newspapers in the Union,

and in 1880 641 periodicals of all kinds. In 1890 there

were 797 published in the United States and Canada;

New York had 110, Ohio 104, Pennsylvania 90, Wiscon-

son 87, Illinois 74, and Missouri 45. Ninety-one were

daily. The largest book hitherto published in America

in the Gei-man language is an encyclopaedia, edited by

Dr. Alexander J. Scliem. It is the German Conversa¬

tions-Lexikon, with copious American additions origi¬

nally.

Germany.—The general opinion of all nations is that

Germany was the birthplace of printing. The claims of

only two places besides Mentz have ever been entertained

in this connection by any large number of persons. They

are Haarlem, in Holland, and Strasbourg, in one of the

provinces lately taken by Germany from France. It

seems incontestable, however, at this period of time, that

whatever may have been done at Haarlem the work led

to nothing. It was not printing from movable types, cast

in a mold, and it is doubtful whether any typographical

remains of a period antecedent to the beginning of an

office at Mentz are extant. As related elsewhere, Guten¬

berg began his attempts at printing in Strasbourg, re¬

moving to Mentz about the year 1444. From the time

when the forty-two line Bible was published it is appar¬

ent that work on it must have begun as early as 1450.

The quarrel between Gutenberg on one side and Fust

and Schoeffer on the other resulted in the establishment

of two printing-offices in Mentz, which continued until

the sacking of the town in 1462, when the art, hitherto

kept a secret, was spread everywhere, as the workmen

were compelled to earn their subsistence in new places.

Fust and Schoeffer began again at Mentz, and Guten¬

berg at Eltville, a village not far from that city. The

work there did not appear under his name, but the types

were his. The office passed into the hands of relatives

by marriage, Henry and Nicholas Bechtermlintz. After

them it was in the possession of the Brothers of the Life

in Common.

Printing seems to have next been done at Bamberg.

The date 1461 has been assigned for this, and the name

of the printer is given as Albert Pfister. Claims are also

made that work was done in Strasbourg in 1458, by Men-

tel and Eggestein. Ulric Zell began at Cologne in 1462,

Gunther Zainer at Augsburg in 1468, Henry Keffer at

Nuremberg in 1469, Helyas Helye at Mlinster in Argau

in 1470, Peter Drach in Spire in 1471, John Zainer in Ulm

in 1473, Lucas Brandis in Merseburg in 1473, Conrad Fy-

ner in Esshngen in 1473, Lucas Brandis in Lubeck in

1475, Conrad Blauberen in 1475, M. Q. and G. Reyser in

Eichstadt in 1478, Dold and Reyser in Wurzburg in 1479,

and Marcus Brand in Leipsic in 1481. Vienna did not

have a printing-office till 1482, and Munich till 1500. The

art spread with great rapidity. There were sixteen mas¬

ter printers in Strasbourg before 1500. Schoeffer's office

in Mentz did much work, but that city was soon sur¬

passed by both Strasbourg and Cologne. In the last-

named place twenty-two printing-offices existed before

1500. Ulric Zell, who dwelt there, was the first of the

early printers, after the triumvirate, who made a repu¬

tation. Nuremberg had the chief printing-office of the

231

|