Columbia Library columns (v.2(1952Nov-1953May))

(New York : Friends of the Columbia Libraries. )

|

||

|

|

|

|

| v.2,no.3(1953:May): Page 19 |

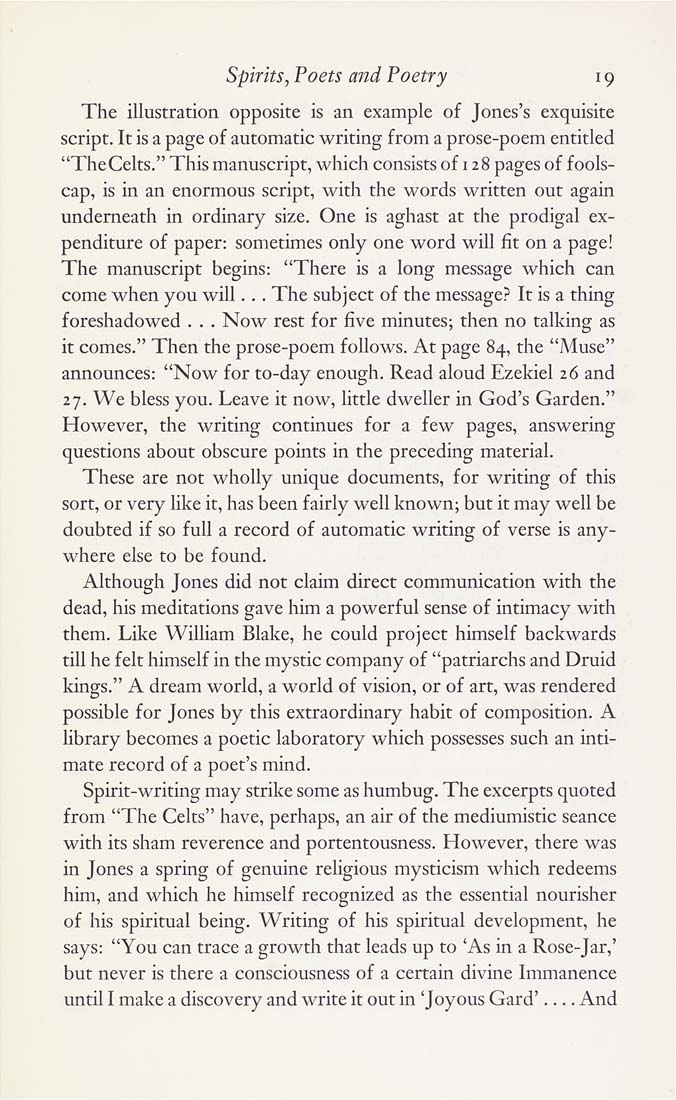

spirits. Poets and Poetry 19 The illustration opposite is an example of Jones's exquisite script. It is a page of automatic writing from a prose-poem entitled "TheCelts." This manuscript, which consists of 128 pages of fools¬ cap, is in an enormous script, with the words written out again underneath in ordinary size. One is aghast at the prodigal ex¬ penditure of paper: sometimes only one word will fit on a page! The manuscript begins: "There is a long message which can come when you will. . . The subject of the message? It is a thing foreshadowed . . . Now rest for five minutes; then no talking as it comes." Then the prose-poem follows. At page 84, the "Muse" announces: "Now for to-day enough. Read aloud Ezekiel 26 and 27. We bless you. Leave it now, little dweller in God's Garden." However, the writing continues for a few pages, answering questions about obscure points in the preceding material. These are not wholly unique documents, for writing of this sort, or very like it, has been fairly well known; but it may well be doubted if so full a record of automatic writing of verse is any¬ where else to be found. Although Jones did not claim direct communication with the dead, his meditations gave him a powerful sense of intimacy with them. Like William Blake, he could project himself backwards till he felt himself in the mystic company of "patriarchs and Druid kings." A dream world, a world of vision, or of art, was rendered possible for Jones by this extraordinary habit of composition. A library becomes a poetic laboratory which possesses such an inti¬ mate record of a poet's mind. Spirit-writing may strike some as humbug. The excerpts quoted from "The Celts" have, perhaps, an air of the mediumistic seance with its sham reverence and portentousness. However, there was in Jones a spring of genuine religious mysticism which redeems him, and which he himself recognized as the essential nourisher of his spiritual being. Writing of his spiritual developmenr, he says: "You can trace a growth that leads up to 'As in a Rose-Jar,' but never is there a consciousness of a certain divine Immanence until I make a discovery and write it out in 'Joyous Gard'___And |

| v.2,no.3(1953:May): Page 19 |