|

|

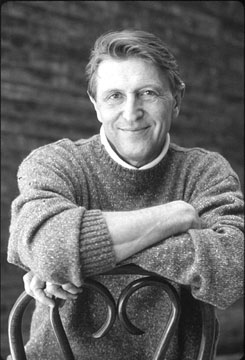

Andrei Serban

|

Hamlet as a man of action. House lights that come up to include the audience in the speech "To be or not to be." A parade of publicity posters displaying Hamlets from Sarah Bernhardt to the present. These and other startling elements in the production of Shakespeare's "Hamlet" that was presented at the Public Theater earlier this month are the hallmark of Romanian-born director Andrei Serban, who is Professor of Theater Arts in Columbia's School of the Arts. His innovative staging of the "Hamlet" blended ideas and methods from eclectic theater traditions, from Kabuki to Brooks.

This intellectually challenging and unexpected approach to his material has made Serban one of the most respected and sought-after directors of the contemporary theater. He is the recipient of both the Tony and Obie awards, as well as a Life Achievement award from Romania. He recently received the Society of Stage Directors & Choreographers' prestigious "George Abbott Award," honoring 21 artists who have made a major impact on the theater during the twentieth century.

"My idea of Hamlet is not as a romantic character, a kind of Romeo with a problem, which is how he is usually done," Serban explains. "Romeo with an existential complex: that's completely banal to me and of no interest."

Serban's Hamlet was played by Liev Schreiber, a 32-year-old New York actor on the verge of becoming an international star. Schreiber first gained attention for his performances in independent films, including "Walking and Talking" and "Daytrippers" (directed by Columbia Film Division alumni Nicole Holofcener and Greg Mottola, respectively), and he recently starred as a cuckolded husband in the feature "A Walk on the Moon" and as Orson Welles in the HBO movie "RKO 281" (directed by another Columbia Film graduate, Ben Ross). Schreiber also earned rave reviews as Iago in "Cymbeline" directed by Serban for the New York Shakespeare Festival in Central Park last year.

"Liev was extraordinary in 'Cymbeline'--we worked very well together," comments Serban, adding that in a reversal of standard procedure, he was "cast" as director of "Hamlet" by Schreiber and George Wolfe, producer of the Public Theater/New York Shakespeare Festival.

Serban's approach to Hamlet was collaborative, drawing on qualities Schreiber brought to the role as an actor. "To me," says the director, "Hamlet is a hero like Prometheus. Like Prometheus he is unhappy with the status quo; he wants the total truth, and sacrifices himself for the truth, for the fire. I want to see this big man with a volcanic temperament, who is not at all a weakling, who is not at all a confused intellectual impotent, the way he is done usually. He is a man of action who is so deeply honest or concerned that he doesn't know what the right action is."

From Serban's perspective, the play is about the awakening of conscience. "To be asleep in the conscience means to be sinful. Everybody's asleep in the court of Claudius; they are all happy, as if they're under a big hypnotist. It's comfortable, it's a hypnosis. The economy's doing well, the country's prosperous, the wars are under control, we can all just have nice times." Serban sees Hamlet as a kind of Everyman who searches for the path to truth, stumbles along the way (by killing the wrong man, Polonius), but who vindicates himself. Serban's reading of the play approaches a Biblical interpretation. "Hamlet sets things right in his world by sacrificing himself for the truth, which in a way is what the great messengers did," he says. "Horatio stays on the planet to give the message of Hamlet: that if you look for the truth and don't let the lie seduce you, maybe this planet can be purged of sin, of evil."

When Serban is asked about the eclectic techniques evident in his work, he explains that he uses "whatever works, whatever makes sense for the scene." Discussing his unconventional lighting in "Hamlet," he references his mentor Peter Brooks' philosophy, "In the theater, the actors and the audience are in the same bed. 'To be or not to be, that is the question,' is everyone's question, not only the actor's. That is why the light comes up. It opens up the question to the audience. It makes members of the audience feel that they are part of the question. It involves them in the best way possible, in the conscience."

Serban has been teaching at Columbia since 1992, where he is director of the Oscar Hammerstein II Center for Theater Studies and heads the M.F.A. acting program. He has also taught at the Yale School of Drama, Harvard University, and the Conservatoire de Paris, among other programs. He began his directing career in the U.S. in 1970 following studies at the Theater Institute in Romania; his extensive credits include "The Cherry Orchard" at Lincoln Center's Vivian Beaumont Theatre, "Agamemnon" and "The Seagull" at the Public Theater, "The Merchant of Venice" at the American Repertory Theatre, and "The End of the World" by David Lan at the Royal National Theatre in London. Since 1980, Serban has directed operas worldwide; his most recent production was "The Ring" at San Francisco Opera. He served as General Director of the Romanian National Theatre from 1990 to 1993.

Serban is in Paris this month to direct Molière's "The Miser" for the Comédie Française.

|