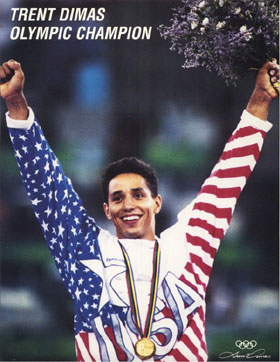

On a hot morning during the 1992 summer Olympic games, Trent Dimas, now 29 and a student at Columbia's School of General Studies (GS), found himself running down a street in Barcelona Spain, late to meet Katie Couric for a live Today Show interview.

Around his neck, Dimas wore an Olympic gold medal he had won the night before, having completed an almost flawless high-bar routine in the men's gymnastics competition. Suddenly, the ribbon that held the medal snapped, and Dimas watched the medal drop to the ground. When he picked it up, it was dented. Now, when he thinks about having it fixed, he always chooses not to, deciding that even the scratches on his most hard-earned possession are reminders of an incredible 16 days in his life.

Until Dimas stuck his final dismount, few had expected him to place, let alone win the men's high bar event. The films of his victorious moment show Dimas' face slowly register shock, then exuberance.

Dimas had trained 21 years for this moment, only squeezing in school when he could. Now, Dimas doesn't want to make school secondary. Last fall, he embarked on the post-athletic phase of his life, committing himself to finishing college and changing careers. With a position at Momentum Inc., a sports marketing firm, Dimas moved to New York from Colorado, and applied to Columbia's School of General Studies.

He was convinced the University was out of his reach, a common feeling among students who have interrupted their education to pursue another passion, said Peter Awn, dean of GS.

Still, even though he was nervous, Dimas said, "I remember getting off the subway at 116th and Broadway, and walking through those gates. And I thought 'there is no other place I want to be.'"

Now that he's here, the rigor of school is familiar. "It's just like gymnastics," he said. "If I have a great instructor, I can expect to learn. So far, coming to Columbia has been like having an Olympic coach training me in academics."

That's high praise coming from someone who until three years ago spent almost every day training with Olympic coaches. Dimas began gymnastics lessons when he was 5. The son of evangelist parents, he and his brother Ted were home schooled, competing on karate, soccer and gymnastics teams in the afternoons. Then, the time came to choose one sport and give up the rest.

So why gymnastics?

"We were huge cartoon fans," said Dimas. "Gymnastics was the closest thing to being a super hero."

Once Trent and his brother started attending public school in middle and high school, they would train from 6 a.m. until 8 a.m., then go to school until 2:30. Then, it was back to the gym. Other than the few hours in school, the rest of the day belonged to gymnastics.

In 1988, both Ted and Trent tried out for the Olympics but neither qualified. Trent was 1989's blue-chip gymnast, having been offered full athletic scholarships to every U.S. university that had a gymnastics team. In his freshman year, with both brothers on scholarship at the University of Nebraska, competing on what was at the time America's strongest men's gymnastics team, they achieved the pinnacle of NCAA sports: the University of Nebraska's team became the National Champions. But then Trent walked away from his scholarship and his studies to give the 1992 Olympic try-outs his all. This time, he made it.

AT THE OLYMPICS

Nobody expected Dimas to do as well as he did. That was the year the Unified Team took the spotlight, with Vitaly Scherbo sweeping six individual events, the all-around and a team gold medal. Scherbo did not, however, qualify for the high-bar finals. Dimas did. The high-bars had always been his strongest event and he had been perfecting his routine for five years.

Watching Dimas' winning routine is spectacular. Even to someone who knows little about gymnastics it is clearly an almost perfect performance. And watching Dimas' face as he lands square and sticks the final dismount, it is clear he can not believe he has done it.

"The difference between making a perfect routine and falling off that bar is a quarter of an inch," he said.

POST-OLYMPICS

After winning the 1992 Olympics, Dimas worked briefly as a gymnastics coach at the University of Arizona, rebuilt a family home, fell in love and took time to bask in the glory of his victory, acting as a spokesperson for his corporate sponsors.

"It's important to balance what you have and be able to give back," he said. He also worked charity events, making public appearances for causes he believes in like the Starlight Children's Foundation.

He attempted to make the 1996 Olympic team, but did not qualify for the Olympic Games. Still, he said, "I learned so much about myself. It taught me a lot about dedication and failure. It's really tough to salute a judge and walk on to the floor when you know your body is not up to the task. Still, I went out there and did the sport for the love of it."

NOW WHAT?

Two years ago, Dimas said to himself: "Here is Trent Dimas. Now he's 27 and he hasn't finished his college education. The Olympic games are like no other event, but when you get out of the athletic arena and people still look at you as an athlete ... sometimes there's a bad stigma that comes along with that. I think that's a shame. A lot of athletes give a better part of their lives to their countries, but in the end we have to make up time lost in the so-called real world."

But in fact, said Awn, the strength of GS is that it recognizes that there is no single "real world." Its students arrive at GS often having had non-traditional, but unparalleled life experiences.

"Our students come from hundreds of different places in life," said Awn. "They're world-renown chefs, ambulance drivers-turned novelists, award-winning production designers and New York Times reporters."

In admitting students, the school looks as much at life experience and in-depth interviews as it does at scores and past transcripts. Once admitted, GS also recognizes that every student wants the education to take him or her to a different place, and thus the school offers schedule flexibility to accommodate working students, and allows students to design interdisciplinary majors if they so desire.

Having worked as a corporate spokesperson, Dimas wanted to experience the other side of the sports marketing table. He is now working to design a specialized communications major, and concentrating on completing his core requirements.

"When I first started working with Trent, I saw a certain ferocity of discipline that your ordinary Joe doesn't have," said Andrea Solomon, assistant dean of students at GS and Dimas' academic advisor. "He's been doing quite well, and he's a pleasure to work with - a real gentleman."

Dimas admits he finds New York a culture shock, having spent most of his life in New Mexico, Utah and Colorado. But he's busy, and at the end of the day he wants to spend all his free time with his wife Lisa, and his golden retriever, Sugar Bear.

He still does some appearances and particularly enjoys working with children. He never likes to take his gold medal to public events - unless the events involve kids.

"For the kids I always try to take it," Dimas said. "They like to hold it or wear it - children can be convinced that it's within each of them to go after the seemingly impossible dream."

|