|

|

|

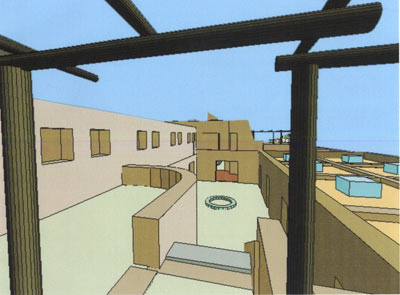

Architect's drawings of the Columbia facility to be built in Egypt

|

Columbia will launch an archaeological fieldwork and research program in January 2002 in a desert region of southern Egypt that has a rich past in the development of early Christian sects, inland agricultural economies and urbanism. The project will include the construction of a small student residence hall and research center, beginning this fall.

Plans for the program in the Dakhleh Oasis were developed by Professors Roger Bagnall and Lynn Meskell, who will serve as co-directors. Bagnall is a leading historian of the Hellenistic and Roman worlds and an expert on Greek papyri who is chairman of Columbia's Classics Department. Meskell is an archaeologist who specializes in Egypt. An assistant professor in the Anthropology Department, her research includes gender and social relations in ancient Egypt.

Bagnall said the Columbia program will be based on the archaeological site of Amheida, part of a region studied by the long-established Dakhleh Oasis Project. Amheida was settled in the third millenium BCE and occupied through the fifth century. A city named Trimithis during the Roman period, the site was the location of a Roman military camp and includes many buildings visible above the surface of the sand, Bagnall said.

"The Dakhleh Oasis Project provides the chance to study Egyptian settlement patterns and urbanism over a period of nearly three thousand years," said Bagnall, noting that the site is likely to yield important finds, ranging from wall paintings to papyrus to food remains. A test trench dug some years ago yielded mythological wall paintings, Bagnall said.

The project highlights a renewed interest in archaeology at Columbia, which has appointed three new faculty members in the field and will open a Center for Archeology.

International scholars at the Dakhleh Oasis Project, currently under the direction of A.J. Mills, an independent Canadian archaeologist, are studying the relationship between human activity and environmental change from the middle Pleistocene to the present. Many of the participants are natural scientists studying landscape, climate, flora and fauna. "The degree to which the DOP has fostered scientific work in collaboration with excavation and the study of texts is unique in Egypt and unusual anywhere in the ancient world," said Bagnall.

Bagnall said Amheida is very rare in Egypt because it provides a long chronological period for a settlement and at the same time has not been "damaged, previously excavated and is of significant size." Unlike Nile Valley settlements, where many archaeological excavations have been carried out, the oasis is a drier environment, and thus preserves organic materials far better.

Because it was not flooded by the Nile every summer, the oasis could produce crops like olives, dates, and grapes far better than the Nile Valley. Wine and olive oil from these "high-value" crops were transported by animals to the valley and sold, said Bagnall. "This region provides an important setting to understand the development of ancient inland economies," said Bagnall.

The site's nearest equivalent is Kellis, also in the same oasis, which has produced exceptional finds during 12 years of excavations, including three of the earliest fourth century Christian churches found anywhere. But Kellis remained a village, unlike Amheida, which grew to become a city. "It [Amheida] is likely to produce a richer variety of architectural types and range of finds, including documents on papyrus, clay and wood. To date there is not a single archaeological project in Egypt which involves the excavation of a site with a comparable depth of material and which has been carried out to the highest standards of modern archaeology," said Bagnall.

Ground will be broken in November on a 16,000-square-foot residential and research facility that will house Columbia undergraduates enrolled in the semester-long field work program, as well as faculty and staff. In addition to living space, the building will include dining facilities, a computer lab, photo darkroom, library, and prayer room for the Egyptian staff. Using the traditional mud brick construction of the region, the cost of the building is estimated at $4 per square foot. The program will be the first Columbia-run excavation in the Old World since Professor Edith Porada's work in Cyprus 30 years ago.

The two-story building will be built outside the regional capital city of Mut about 30 minutes from the excavation site and will accommodate 15 students during the program, which will run each year from January to the end of March. Following six weeks of field work and instruction in Dakhleh, students will travel for two weeks to sites and museums throughout Egypt, ranging from Aswan to Alexandria. Several more weeks will be spent in Cairo or Alexandria preparing major independent projects.

Bagnall and Meskell will provide instruction in archaeological fieldwork and jointly teach a course on Egyptian archaeology and history. A seminar on the ecology of the Dakhleh Oasis and the Sahara Desert will be developed in collaboration with Columbia's Biosphere 2 campus. Pamela Jerome, who teaches in the School of Architecture's Historic Preservation program, will conduct a week-long field school on building conservation. In addition, through graduate studies, Bagnall expects the program will bring together scholars from several other Columbia departments, including art history, classics, history, Middle East and Asian Languages and Cultures as well as the natural sciences, such as geophysics.

The program has received financial support from the Provost's Academic Quality Fund and the Arts and Sciences division. In addition, an initial fundraising goal of $180,000 has been established. Nearly $70,000 has been raised to date.

Bagnall hopes to establish a museum reconstruction of an ancient building on the site, once excavation is underway. "Mud brick is very fragile," he said. "You couldn't have people trampling over it, like stone. My dream would be to recreate a building on the site from new mud bricks and display objects found in their context."

|