EVENTS

Upcoming

Ongoing

Locations

116th and Broadway

New York, NY 10027

212-854-1754

Intercampus Shuttle

125th and Broadway

New York, NY 10027

212-854-1754

Manhattanville Loop Shuttle

61 Rte. 9W

Palisades, NY 10964

845-359-2900

Shuttle Service

Community

Columbia Neighbors is part resource guide, part community news and storytelling hub, part gathering place. It is for everyone in the communities surrounding our campuses in Upper Manhattan.

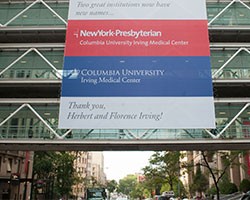

The Office of Government and Community Affairs is the University’s primary liaison with federal, state, and local government, as well as with residents, community leaders, and civic organizations in surrounding neighborhoods. The CUIMC Office of Government & Community Affairs maintains a similar role for communities surrounding the Irving Medical Center.