|

|||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

As so many things in life, my hour-long conversation with the actor happened thanks to a chain of co-incidences that were hardly coincidental. In September 2007 when at the San Sebastian Film Festival, I was told about an Italian film shot on location in Kyiv, Ukraine by Italian director David Grieco. Upon my return to New York, I called Mr. Grieco to discuss the possibility of screening his picture for the Ukrainian Film Club of Columbia University. It was then that I learned that the lead in the film was played by none other than Malcolm McDowell.

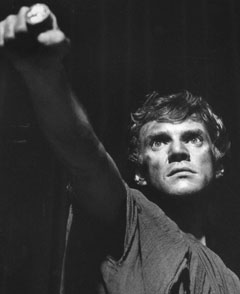

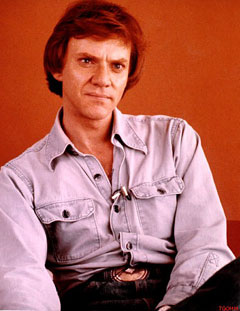

Every cinema buff has his own relationship with his favorite actors. McDowell has always been my favorite, since at least 1975 when I saw him for the first time in O Lucky Man. The film, which criticized British society, was widely distributed in the Soviet Union. It became an instant success with Soviet audiences, particularly youth. While they did not care much for its critical message - they were over-fed with Communist criticisms of capitalism - they relished in all its depictions of Western decadence, depravity, excess, consumerism, and other birthmarks of capitalism that had the irresistible attraction of forbidden fruit. Malcolm McDowell’s starry-eyed protagonist Mick Travis became something of an unintended hero, a symbol of passive resistance to Soviet totalitarianism. The actor briefly resurfaced behind the Iron Curtain playing the role of Nazi officer von Berkow in the 1979 film Passage, which was also distributed in the Soviet Union. His other films, notably Stanley Kubrik’s The Clockwork Orange remained out or reach until the collapse of the Soviet empire. His appearance in Evilenko necessitated his coming to Ukraine with an entire Italian film crew for on location shooting in Kyiv and the environs. Sadly, the release of Evilenko did not mean McDowell’s return to Ukraine and to his many fans who still remember and treasure him as a great actor and a distant echo of their own rebellious Soviet youth. The film was never distributed there, which says a lot about the country’s not so distant Soviet past. The reason is as banal as it is undeniable - Ukrainian distribution is totally dominated by Hollywood and Russia, who promote films of their own making and with their own agendas in mind. With its orientation toward the ignored, the alternative, the experimental, and the marginalized, the Ukrainian Film Club of Columbia University seems to be a natural forum for Evilenko. It was on the occasion of its screening scheduled for March 25, 2010, that the conversation between Malcolm McDowell and the club’s founding director Yuri Shevchuk took place. YS: You once said Lindsay Anderson taught you how to be a good actor. What does it mean to be a good actor? MM: Lindsay Anderson was a remarkable man, and I was very, very fortunate to meet him, to work with him, and to have him as a friend for thirty years. What he taught me, of course, besides life lessons and the philosophy of life.… In terms of acting he re-enforced in me what I already had. He didn’t really teach me to act. I had it already. My style of acting is not really [one] of naturalism. It’s heightened, it’s real, but not realistic. Lindsay’s mantra was to elevate acting into an art form. I don’t want to get too pompous about it. But it is to say that it’s not just to do it naturalistically. To shape a performance in a style that would have poignancy and humor. And that’s what I think he saw in me, and he said he saw in me, when we first met all those years ago. It was something that was already there. He said to me once, “You are a very Brechtian kind of actor.” I was twenty-three years old at the time. I didn’t know what the hell he was talking about. What he meant was: when I am performing I am not afraid to tell the audience that I am acting, but that they will believe me anyway. YS: If I were a young man aspiring to be a good actor, could you tell me what faculty is most important to have? MM: Of course, it would have to be confidence, but, of course, you can’t teach that. Either you’ve got it or you don’t. And confidence, of course, can come over doing something for many, many years, or you could have it as a brash young man. It’s a very important ingredient to acting, I think, or performing of any kind. It’s believing that you can do it. YS: You seem to be very intuitive in your acting, often at the expense of studying the character you play, and if it is real-life figures like H. G. Wells or [Russian serial murderer] Andrei Chikatilo you forgo studying the facts of their biographies. So is it preparation or pure instinct? MM: You can’t do a part until you know the lines. It’s academic. You cannot do anything until the lines are learned. So I spend most of my time learning the lines, going through it like a parrot. And go through it, and go through it, and go through it, and go through it.… Then I can actually begin to perform, because I never, ever want to be thinking in a scene, “Oh, what’s the line?” or “Oh, this is a good line,” or “Now I know what I say.” So the line should come out of your subconscious. I am a very technically prepared actor who relies totally and utterly on instinct. YS: A happy combination of both instinct and technique. MM: I don’t know how to explain that, because I think you do a lot of work when you are just learning the lines, subliminally, [acting] the scene. Even if you’re just trying to get the lines memorized. Do I do a lot of work on the technical stuff? Very rarely. It depends. If I am playing a schizophrenic [for example], what does that mean? It means a man who believes he alone is right and everybody else is wrong. So what’s the big deal there? It’s simple, you know. And that’s the very definition of schizophrenia or psychosis. Playing Evilenko was a little bit different experience in my acting career. Because he was such a monster to play in terms of the emotional content, I really went more for the physicality of the part. Having got the physical aspects—the walk, the way he moves, everything else fell into place. He is a monster, of course, he does monstrous things, but in the end, even though he killed more than fifty children, you realize he is mentally insane. Really, who are we to judge that? We can’t, we can only judge the actions, but if someone is mentally insane, it’s by a quirk of fate. It’s unfortunate. It was a very rewarding role in many ways. I thought it was going to be very depressing. But it wasn’t. YS: When you are approached with an invitation to play a particular character in a film, are you attracted by something you already understand, something you are familiar with in a character, or on the contrary, something you do not know much about, like, say, the serial killer represented by Evilenko. And if the latter is the case, how much reading and preparation do you do? MM: Of course, the character [of Evilenko] is based on a real person and a very famous one in the annals of crime, and it is Andrei Chikatilo. But I am not playing Chikatilo. The only thing is that David [Grieco] gave me a lot of tapes, documentaries that he made of this man, and tapes that he’d done for his book. David met with Chikatilo in Moscow before he was executed. I was watching it and told David I don’t really need to see any other stuff because I am not playing him. Why do you want me to see all this? I had to come up with my own thing. I had all the material in an apartment in Kyiv on DVD or video tape. I was unpacking and glancing at the [television] screen as I walked past. And at the very end of these tapes there’s one shot of Chikatilo in the court room, when he is behind bars in this cage. As the camera comes to him, he looks into it and gives this extraordinary smile. I saw this and I immediately thought, “That’s how I play it!” YS: When one looks at the parts you played, one gets a contradictory impression. When you play Mick Travis in If…. and O Lucky Man, you seem to be indentifying quite a lot with the your protagonist. When you were about to play the serial killer Evilenko, you said in an interview, “I am not going to take even an inch of myself to that part. I’ll go Lawrence Olivier on it. I’ll play it, as it were, from outside. So what is your approach to the characters you play? MM: Except for this rare occasion with Evilenko, basically you are taking care of the emotional needs of the character, not the physical ones so much. That’s very important. There are a lot of really good, great actors and it does not matter how they find the performance as long as they end up with it. That’s the only thing that’s really important. It is pure performance. I basically didn’t know what I was doing. There was no trick, there was nothing. I just was. YS: Is it fair to say that you go with the flow and you don’t really know what’s going to be at the end of the part you play? MM: I never know what’s going to be at the end. You have a general direction that you obviously want to go in. Then you start breaking it down into scenes and then into moments, and then you just concentrate on that. You are not quite sure how it’s going to string together. Also you have to be totally in sync with the director, and he has to be in sync with you. YS: Lindsay Anderson was a singularly towering figure in your career. But you also worked with Stanley Kubrick. MM: He [Kubrick] was absolutely huge, a mammoth talent. An extraordinary man and an extraordinary intellect. Completely different to Lindsay Anderson. They were poles apart. Lindsay Anderson was a man who wore his vulnerabilities on his sleeve. You could see he was a very passionate man who could be wounded easily. Stanley never ever showed any emotion at all. He was much more clinical, much more intellectual in his stuff. He didn’t care how I got my performance as long as I got it. He didn’t understand anything about the performance, [to him] how an actor played a scene was a little bit like [a piece] of chamber music. It flows and then there’s a quiet part, then a loud bit. Then you let it go, then you bring them in. That’s something I have learned from Lindsay. Stanley wasn’t interested. He couldn’t care less. I didn’t discuss it with him because it was pointless. He’d just get on with it. I’d do my own thing and use it. If he liked it, great! YS: Different as they both were, you seemed to get away with murder with both of them somehow. You drove your point and persuaded Lindsay Anderson to do things the way you saw them. The same thing, much to your own surprise, happened with Stanley Kubrick. You said something that an actor was not allowed to suggest. You thought that would be it for you.

MM: I heavily relied on my instincts. And my instincts had told me what to do. I listened to them and reacted accordingly, so that you know my instincts gave me the sequence of “Singing in the Rain.” [It was] an improvisation that came up. A whole chunk of the film is inprov. [Kubrick] liked it. Lindsay did not like improv at all. In fact I don’t think I ever said hardly a word outside of what was in the script. He improved, refined, refined, refined, and what was in the script was what he wanted. YS: But, on the other hand, you could get away with offering him the idea of making an entirely new film. You told him after If ….hadwon the Palme d’or at Cannes, “We are such a great team. Let’s do another film.” MM: Yes, [but it] took a lot of persuading. He didn’t want to do it at first. I knew he’d do it in the end. He had to go slowly, slowly, slowly. I wrote the treatment, and he derided me and told me how bad it was. I said, “You’d better get used to it, ’cause it’s gonna be your next film.” And he goes, “Is it?” “Yes, it is.” “Then you’d better call David Sherwin,” who had written If …. and who we wrote [O Lucky Man!] together with. We sat down and wrote this, and he’s a dear friend of mine. I am going to do another script of his later this year in England, I am happy to say. YS: What is it about? MM: The title is When the Garden Gnomes Began to Bleed. It’s a magnificent script about a writer who refuses to compromise. He’s a scriptwriter [like] David Sherwin, and [he] has a great idea that Hollywood wants to buy. They want to jazz it up completely, change, and ruin it. He has no money. He is absolutely broke. His house is being repossessed, and he says, “Fuck yourselves!” His wife and daughter just can’t believe that he did it. Then he goes and tries to get what in England is called social security. The interview [in their office] goes something like this: “What do you do?” Of course, they refuse to give him any money. He takes them to court by saying, “They say thinking time does not count,” and he wins the case. Who is to say what is an artist? It took Picasso seventy years to realize [how] to draw a straight line. The film script is about the right of the artist to create. YS: Who will be directing the film? MM: I can’t really talk about it because they are in negotiations. The producer is Paul Cowan. I seriously think it will be a wonderful film and I’m excited to be working with my old friend again, with whom I started my film career [David Sherwin also wrote the film scripts of If … (1968) and Britannia Hospital (1982), both directed by Lindsay Anderson]. YS: Besides Lindsay Anderson and Stanley Kubrick, were there other directors who had a considerable influence on you as an actor? MM: The thing is that I worked with these directors at the beginning of my career when I was the most impressionable. They meant more than any others to me because I was so young and impressionable. I have worked with incredible directors since. Particularly I loved to work with Blake Edwards [Sunset, 1988], John Badam [Blue Thunder, 1983] and Paul Schrader [Cat People, 1982]. YS: What movie did you do with Paul Schrader? MM: A very interesting horror movie called Cat People. Paul is a strange man, but I like him very much. He is a very talented man. I like Cat People. He did a great job on that with Nastassja Kinski. It was a movie made in the 1980s. YS: Do you like working with young directors? MM: I do. It’s fun to see them. They get very enthusiastic. They haven’t been doing it that long, so they are not really jaded. It’s rather invigorating for me to work with young directors. I love it. YS: When one looks at the characters you have played, it is either a downright villain, as in Clockwork Orange, or, even if it’s a positive guy, he all too often has something devilish about him, a diabolic glimmer in his eyes, like Mick Travis in the trilogy of If …., O Lucky Man, and Britannia Hospital. The crowning point in this line of villains played by you is the serial killer Andrei Evilenko. MM: Yes, and nobody saw [the film]. YS: Why is that? MM: It was made by a small Italian company who really didn’t know how to sell it in the foreign market place. It’s a shame, because I think there is a market for this kind of movie. I don’t know what happened. Making a movie is really half the problem these days. The other half is being able to market it. I feel bad because David Grieco [who wrote and directed Evilenko] is one of the most talented people I’ve worked with. He is a brilliant writer, a most incredible director. I would do anything to work with him again. YS: That’s a wonderful thing to say about a person for whom Evilenko was his directorial debut. MM: It was like he’d been directing all his life. He was totally and utterly magnificent. It was one of the most fun collaborations I’ve had with a director since my time with Lindsay [Anderson]. MM: It’s subliminal. I didn’t think about that. I didn’t think of doing that. YS: You do not give the viewer the comfort of thinking, “Oh, I am not him, he is such a monster that he has nothing to do with me. I am such a nice person compared to him.” YS: Why was Ukraine, and not Russia, chosen as the shooting location for Evilenko? MM: [First] because the Russian mafia attached themselves and wanted certain things from these Italians that they couldn’t possibly give. The second thing was that Ukraine, in a strange way, has not quite gone as wholeheartedly capitalist as much as it had in Russia. There was still this very heavy atmosphere of the Soviet empire, which was what we needed. I personally loved it. YS: You once said about your going to shoot in Ukraine, “I am going to a country where one can’t find a good sandwich!” Could you find good sandwiches there? MM: I was joking, of course. Actually the food there is very good. They never stop eating, and it goes on for hours and hours and hours, and then they smoke the thing. Oh, we had incredible food there! Very hospitable people. The guys who worked on the film were absolutely fantastic, incredible. You could see how these people had suffered and come through. This extraordinary race of people. I felt that very strongly. YS: Did you feel you were among the people who are different from Russians, or just a variety of them? MM: Yes, completely different. I really don’t know how to put it into words. Just the ones that I met were so friendly and so nice. Now, a lot of Russians were too, but there was a certain suspicion, I think, in Russia. There was always another agenda, always something else. You never quite believed what you were hearing. Whereas in Ukraine people seemed to be more open even though they didn’t have much. I really enjoyed it. It is a very beautiful country. YS: In this globalized and Hollywood-dominated world, do you see a future for national cinemas of smaller countries like Britain or France, or even smaller ones, like Ukraine? Is there a future for them? MM: It’s not a great future, but I think it’s incredibly important to have a national film business in the countries like Ukraine or Britain or wherever. It really does show the identity of that country much more than a Hollywood movie [whose action takes place in a foreign country] that will only skip over the surface of that country. Like doing a James Bond film in London, that’s not London. It has nothing to do with London or anything else. The movies that Lindsay Anderson made were a mirror to the society in which we lived. They were making comments about it, about what was going on, and how we felt about it. Those were very important films. When you think back, there have been none like these ever since. I can’t think of any. There’s been a couple, maybe. Hollywood wants movies for young kids or big spectacles, with lots of green screen. That’s it. I know. I tried with them. We have a beautiful script [based on] Thomas Mann’s novella Mario and the Magician and there were no Hollywood people really interested [in it] at all. It was very difficult to get going. They just said, “It’s not marketable.” And they’re probably right. But it doesn’t mean we can’t try to get it going, because it’s very important to get good pieces done. Mario and the Magician is a warning against fascism, and it’s entertaining. We are trying to get the money for this film. We are almost there but not there yet. It’s very difficult to get anything going that isn’t aimed at fifteen- to twenty-three-year-olds or huge spectacles like Iron Man. These are incredible spectacles, and [in them] there’s room for everything. I loved Avatar and went to see it twice. Those [films] are amazing spectacles. MM: Yes, I saw it in IMAX and I was amazed by the poetry of it. I liked it enormously as a great evening out. I didn’t come back and think of those poor people.

YS: Do you think Avatar marks the end of the type of film that has a deeper, staying message, that’s not quickly forgotten? MM: There have been serious meaningful films that have won Oscars many, many times recently up against big studio movies. It’s always independent movies that seem to be winning. They don’t make them any more. It’s so hard to get one made. James Cameron is a kind of genius. I just worry that in the hands of other people two- or three-hundred [million-]dollar movie that’s not in James Cameron’s hands could be a total fiasco. It sets the bar so high in terms of the visual [aspect of the film]. They are not cheap. Their budgets are often bigger than the gross national product of many African nations. It’s crazy. YS: Has there been a part that you have always wanted to play and haven’t played so far? MM: No. I’d say if I die tomorrow, I’d be happy. I can’t complain about the parts I played. There are parts I’d like to do if possible, but I don’t go around [thinking] I’m dying to play them. I know, pragmatically it’s probably not gonna happen. So I just really let it go. Otherwise I’d be full of angst. There’s no point. There’s a couple of wonderful parts right now that if they come off it would be great. One of them is the magician in the [film based on the] Thomas Mann [novella] and another is a wonderful script written by Bo Goldman, who’s a double Academy Award winner. He wrote the screenplay for [One Flew Over the] Cuckoo’s Nest [1975], and also Melvin and Howard won the Academy Award for [his] screenplay [1980]. He is a great Hollywood screenwriter, a real master, and his is a great art form at its best. I’m hoping we’ll get the money at some point. YS: In O Lucky Man, which I absolutely love, one of my favorite scenes is when Rachel Roberts’s character says, “Smile, Mr. Travis,” and he readily obliges. Towards the end of the film when he is again asked to smile by the film director played by Lindsay Anderson, he refuses, he sees no reason to smile. He is jaded, burnt out, and disappointed. Some thirty-seven years later, Malcolm McDowell, who strongly identified then with Mick Travis, seems to have no problem smiling. MM: I think, simplistically yes, I have a lot to smile about. I’ve led a blessed life, I’ve got a fantastic family and children. Really, I am very lucky. I have an awful lot to smile about. Mick Travis in those days set out as an innocent, just a total innocent who was beaten from pillar to post, beaten down, beaten down by the system. Of course, at the end of it, when he is asked to smile he has nothing left. Shooting this, I remember, Lindsay was the one who asked me to smile and then he hit me with this [screenplay]. YS: It was wonderful! MM: It was an incredible moment. We shot this twenty times, and, of course, he ended up using the third take. By the way, there is a very interesting documentary I’ve made about my relationship with Lindsay Anderson. It’s called Never Apologize. You can find it [at] neverapologize.com. I did it as a one-man show on stage, as a tribute to my mentor, Lindsay. It will tell you more about him, my relationship with him, and my love for him. He was brilliant, he was a genius in his writing. He wrote a piece about his last meeting in the desert that he had with his hero, the director John Ford. It’s a really beautiful, moving, and entertaining piece. I used his diaries, letters, everything. YS: What year was it made? MM: It just came out. I don’t know whether you can get it on DVD. YS: We’d like to invite you to be an honorary member of the Ukrainian Film Club of Columbia University. It would mean that you support our efforts to popularize Ukrainian film here in America. MM: I am happy to lend my name to it. YS: Is there anything you would like to say to the viewers of Evilenko? We are going to screen the film on the 25th of March. MM: I’d like to say, “Enjoy it.” YS: That’s a devilish thing to say. MM: I would just say I am extremely proud of it. It is one of my best performances really, I think. Everything that happened in Kyiv in Ukraine helped me very much to arrive at this performance. I will be forever grateful to the people who supported me there, and if you could tell the people that, I would be very happy. I’ll send you a copy [of Never Apologize], and I think you will want to show it because Lindsay really loved the countries that were then behind the Wall. He loved going to Poland. He made a short film called The Singing Lesson in Poland when it was still Communist. He loved Poland and, of course, Czechoslovakia. He used as his director of photography [the Czech cinematographer] Miroslav Ondříček. He was very taken with that. He knew that the people of the East [Eastern Europe] saw his films underground and really appreciated and loved them. If that was also true in Ukraine, then I am very happy and I know he would be.

|

|||||||||||||||