December 1, 2014 |

Reflections on the Ukrainian Film Club’s First Decade:

Interview with Yuri Shevchuk |

| |

In this interview, Yuri Shevchuk, founder and director of the Ukrainian Film Club at Columbia University (UFCCU), reflects on the club’s first decade in New York. Since starting the UFC in 2004, the collection has grown to number hundreds of movies including classics and even some yet to be released. The club itself provides an unparalleled platform for the digestion and discussion of Ukrainian cinema; not even fans of Polish cinema with its undeniably beautiful movie-making tradition have a similar monthly home.

I met with Prof. Shevchuk, who teaches a course on Soviet and post-colonial film in addition to Ukrainian language courses, before one of the club’s off-site screenings at the Ukrainian Museum: Ihor Savchenko’s 1951 Taras Shevchenko. True to the mission of the club, our discussion wandered over into the realm of Ukrainian culture and national identity, where it sat down, made itself comfortable.

You’re celebrating 10 years of the Ukrainian Film Club at Columbia University. How did the idea of a permanent forum for the celebration and criticism of Ukrainian film come up?

|

| Opening night of the “Post-Revolution Blues” Polish-Ukrainian film festival co-organized by the UFCCU in Chicago, August 2007. |

It came up immediately after I started working at Columbia University. I was trying to think of how I might expand the appeal of the Ukrainian Studies Program that was kind of in its incipient stage in 2004. I thought, “Nothing offers itself better as such a popularizing tool as cinema.” That was immediately a kind of self-created challenge because Ukrainian cinema was, as the saying went at that time and still goes today, “in the state of a coma.” Very few films were being produced, and the idea sounded fantastic, very nice, but its realization looked like barely realistic.

My initial concept for the film club was to create something that would depart from what used to be done: namely to show the newest, the freshest, the best films being produced in Ukraine, and only if there is time and no films left, to fill in the gaps with the so-called Ukrainian classics, which everybody who was interested in film could access. So, I went to Ukraine with the express purpose of probing the ground for how many films I could get, and my primary target was new films. I immediately started calling people in Ukraine and pulling strings and simply knocking on doors.

Was the project welcomed enthusiastically or with some skepticism?

|

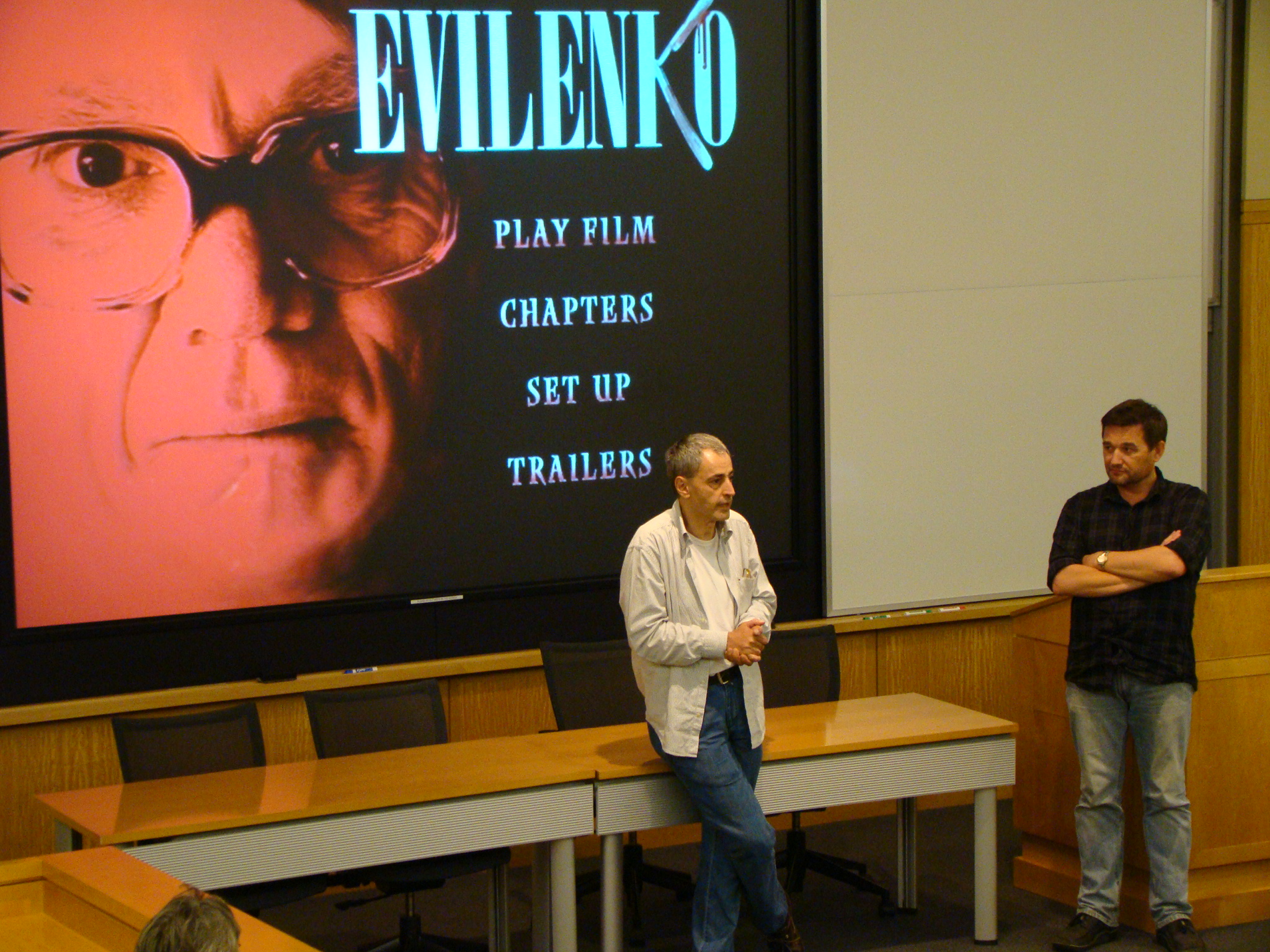

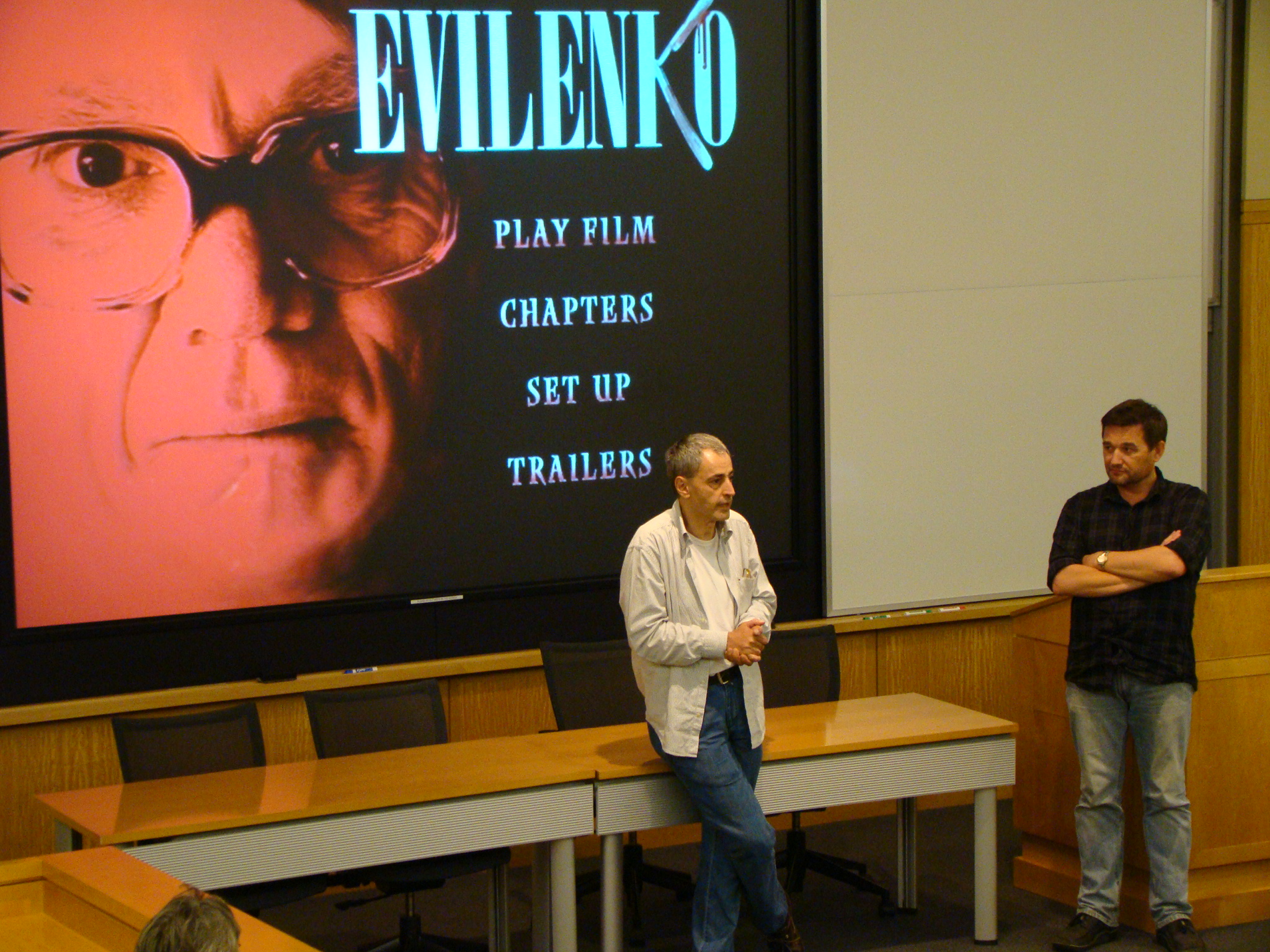

| The UFCCU has been a permanent presence at Harvard University. With the Italian film director Davide Grieco, at Harvard screening of his feature ”Evilenko” in July, 2010. |

One was this prestigious and high-quality industry publication called Kino-Kolo. I simply invited myself to their office and introduced myself to their editor-in-chief, Volodymyr Voitenko – one of the most pre-eminent and respected Ukrainian film critics at the time. He loved my idea and immediately supported me with great enthusiasm. He also introduced me to a number of people – I knew nothing about the Ukrainian filmmaking scene at the time so I was doing everything from scratch. I started frenetically calling everybody and anybody whose phone numbers I could find and there was like a chain reaction because once you meet somebody, they have somebody else’s phone.

I was able to bring with me a little collection of probably five new films; it was a motley crew, really, because they were of all genres. The big breakthrough everybody seemed to be talking about at that time was the feature film “Mamai” by Oles Sanin, Ukraine’s 2003 entry for Oscar consideration in the Best Foreign Language category.

I met Oles Sanin and he was very receptive both to my initiative, my invitation and to the realities of our activity – namely that we were a non-profit, educational initiative that could not pay any money for the rights to screen the film. So there was Sanin’s film, then there was the film by Hanna Yarovenko called “Kinomania,” a feature-length documentary. There were a number of short films, animated films. I was initially helped quite a bit by another Ukrainian film scholar, Larysa Briukhovetska, who runs the film studies program at the National University of Kyiv Mohyla Academy. She basically unloaded everything she could share with us in VHS format. Here the reception was also very enthusiastic. I don’t think people realized how big the challenge there was, because everyone was wondering, “Why hasn’t anybody done this before?”

Our first event was in late October 2004 and we advertised it everywhere as pompously as we could, including in The Ukrainian Weekly. It was in a very modest setting in a room that is absolutely not fit for screening anything, never mind an arthouse film, which is visually very gorgeous and stunning. So many people showed up that they had to open a partition to make the room twice as big, and it still couldn’t seat everyone: between 80 and 90 people.

I myself didn’t have anywhere to sit, and happily I stood with my heart throbbing because I was so very excited and nervous about how it would go. I diligently prepared an intro. I had read everything I could find about Sanin – things that he probably didn’t suspect existed in print about him – about the film; I read the 16th- or 15th-century ballad about the flight of three brothers from Azov that inspired the film.

It was the success of the first event that kind of inspired all of us. From day one, that initiative was very much cooperative. Immediately people who liked film and who liked Ukrainian culture and who liked Ukraine just showed up. The head of the then very vibrant students’ society, Adrian Podpirka, immediately came up with the brilliant idea of designing a website to get the word out. The first website was kind of basic, but it existed and people began writing from all over the world including Australia, Japan, you name it. The reaction both in New York and outside was very welcoming. It gave us an added motivation to keep going and to think of the film club as a permanent investment of intellectual and organizational effort, as something that should be here to stay.

How has the film club changed throughout the decade of its existence and can you tell us about some of the more memorable events?

|

| UFCCU has prepared two Ukrainian film programs (2012 and 2013) for the new international film festival “Hecho en Europa,” San Juan, Puerto Rico. Yuri Shevchuk with Dr. Sonia Fritz, professor of film studies at the Universidad Sagrado Coraçon (from left) and Camille Vandenbunder, Festival Program Director, Alliance Française de Puerto Rico, March 2012. |

Well, it’s a very loose kind of thing, but it has evolved. It doesn’t have any formal membership, though sometimes people write me asking: “How could we please become members of the Ukrainian Film Club? What do we have to do?” No, no publications are required, not even membership fees! We used to put out a donations box, but when donations petered out we stopped.

All the time there are enthusiasts, among students primarily, who like the idea of promoting Ukrainian film and Ukrainian culture with it. Because, really, Ukrainian film is just an excuse; it’s just a vehicle to promote something much bigger and to speak about something much bigger, namely, the entire invisible civilization which is Ukraine, and largely remains unknown despite the fact that it has been in the news. Even today when the media speak about Ukraine, they draw on all kinds of mythologies that have been created outside Ukraine, outside Ukrainian history and culture. What dominates is the inertia, on the one hand, of American ignorance about Ukraine, and on the other hand, as an imposed vision of Ukraine generated in Russian imperial ideology. So the film club thought very strategically that we would generate not only a new discourse on Ukrainian national film, but on Ukraine itself.

And that brings me to the part of your question about the most memorable event we’ve had. Perhaps number one was the American premiere of the feature documentary by Serhii Bukhovsky, “The Living,” which was the crowning event of an international conference conceived and organized by the Ukrainian Film Club with the support of the Harriman Institute in 2008, “Holodomor in Film.” We were trying to get both film specialists and historians involved to analyze how the Holodomor is and is not reflected in film, and why and with what consequences.

So we invited people who work with video and oral history archives of the Holocaust at the University of Southern California, where there are several hundred units of eyewitness accounts of the double victims of both the Holodomor and the Holocaust who survived to tell about their experience. We had a number of historians, and of course we had Serhii Bukhovsky with his entire film crew, with his producer from Paris and his producer from Ukraine, his wife, Viktoria Bondar, and some of the Welsh protagonists who discovered Gareth Jones’s documents pertaining to the history of the Holodomor in their attic.

The following day we had the screening at Harvard University. Eventually the film was invited to another conference modeled on ours at the American John Cabot University in Rome, and they had some of the priests who many, many, many years ago – 50 years ago – unearthed documents in Italian archives pertaining to the reports from the Italian Embassy in Kharkiv about the Holodomor.

We are particularly proud that we’ve provided a platform for a young generation of Ukrainian filmmakers, hosting such filmmakers as Taras Tkachenko, Taras Tomenko, Yelyzaveta Kliuzko. We’ve also hosted a number of foreign filmmakers, like Carlos Rodriquez who made a very interesting feature documentary on Chornobyl. We also had an Italian filmmaker at Harvard University, David Griego with his film “Evilenko” loosely based on the story of the Russian serial killer called Chekatilo. That film was like a metaphor for the dying, agonizing Soviet system if you could reduce it to the story of one cannibal.

The film club is a traveling club, is it not?

|

| Organizers and participants of the KinoFest NYC, April 2013, an outgrowth of UFCCU. |

An important aspect of our activity is branching out, encouraging others to take interest in Ukrainian film. We hit the road because we started getting invitations from all kinds of places: of course, initially, the greatest centers of the Ukrainian diaspora: Philadelphia, Harvard Summer School, Toronto, Detroit.

In Philadelphia we became a known presence because we were getting invited by another enthusiast of film, a devotee really, Andrii Kotliar. He mobilized young people there and we did a couple of very successful Ukrainian mini-film festivals. Eventually, Kotliar branched out, moved to New York, and ended up organizing a very good and very favorably regarded (both locally and in Ukraine) festival called Kinofest. I think they’ve had already four editions of Kinofest and I’m looking forward to the next one this coming spring. By his own admission, Kinofest is a branching-out of our film club.

The University of Toronto started a permanent film series called Contemporary Ukrainian Cinema and I would travel there every semester for at least two screenings. We had a mini Ukrainian film festival in Edmonton; then we had a small, two-day festival at McGill University sponsored by the local Ukrainian student society.

I immediately started probing the ground with bigger outlets, namely the Tribeca Film Festival, saying, “We are here representing Ukrainian film and we would be happy to help you connect to Ukrainian filmmakers back in Ukraine and offer you advice and whatnot.” Slowly some American filmmakers interested in Ukraine started contacting us for different reasons: location scouting or looking for professional help on site as they were shooting their footage.

What sets the Ukrainian Film Club apart from forums for national cinema; does it have any peers? Where does the Ukrainian Film Club stand in the field of post-Soviet film clubs?

In a way we exist in a kind of self- imposed isolation not being terribly interested in film clubs that are out there. At Columbia University I’m not aware of a single outfit that presents itself as a film club. For us, showing the film is only an excuse to speak about something the film represents, about Ukraine, about Ukrainian culture in its infinite manifestations. Film is an excuse to have a conversation, to create buzz, to make people think about things that are larger than the film, both that appear in the film, but also that are significantly left out of the film.

So it’s always, always the case that we have a discussion of the film and very often the discussion is long. And I always make a point of introducing the film to create a larger both social-historical and cultural context against which the viewer interprets the film. It’s not just pure entertainment or pure visual experience; it is primarily an intellectual experience. And in that sense, I think we stand apart even from such hallowed film platforms as the Lincoln Center Film Society or the MoMA film series where films are screened and on very few occasions discussed.

Another difference: unlike any other film club, we are acutely aware – we almost function with the awareness – that we are the only ones: if we don’t do it, nobody will. So we are a lonely warrior in the field with a sense of mission: that we represent something infinitely big and that gives us a self-vision that keeps us going even when sometimes we encounter obstacles.

What’s also important is that we are very picky. From day one, we decided that we needed to be a kind of filter that kept the notion of Ukrainian national cinema uncontaminated by colonialist influences, so we favor films that manifest recognizable attributes of national film. That does not mean that we don’t screen films that don’t, but that for us is another pretext to talk about the current state of Ukrainian culture and the ongoing colonialist influences. From that angle, for instance, we showed a patently anti-Ukrainian film, “Taras Bulba,” by Vladimir Bordko which is simply a propaganda and agitation film. Not only did we show the film, we organized conferences around that film. We invited a specialist in history, a specialist in Russian literature and a specialist in film, and we had a very stimulating discussion. So the intellectual dimension of the film club is very pronounced and probably, without fear of exaggeration, is central.

Also we don’t mince words broadcasting the message about our preferences back to Ukraine and telling them, “The films that you are making can all too often hardly be seen or understood or presented as Ukrainian ‘cause there’s nothing Ukrainian in them.” We try to encourage those who make Ukrainian films that give a voice to the people and a culture that have been deprived of a voice for decades.

How are you celebrating 10 years of the Ukrainian Film Club?

|

| UFCCU has cooperated with the Polish Cultural Institute of New York to bring Ukrainian-themed Polish films to the wider international viewer. With the Polish documentary film director Malgozata Potocka (second left), Jerzy Onuch, director of Polish Cultural Institute (first left), Consul General of Poland in NYC Ewa Junczyk-Ziomecka, Mirka Onuch-Werbowy, February 2011 at the screening of feature documentary Guardian of the Past at the Ukrainian Museum, New York, NY. |

We want everybody to know that we have been around for 10 years, and even more so that we have done a lot of things and, most importantly, intend to do many more things, but not without the support and interest of the community we’re serving. And that is not only the Columbia academic community or the Ukrainian American community, but the American community, those Americans who are looking for something other than Hollywood fare. So we are organizing an American tour for the film “The Guide,” the latest work by the director Oles Sanin, and not unimportantly, Ukraine’s official entry for Oscar consideration in the best foreign language film category.

This tour is going to start at Columbia University on December 2 with the screening of “The Guide,” followed by a screening in Philadelphia the following day, and then by a screening at Harvard University under the auspices of the Ukrainian Research Institute there and then followed by Chicago, Detroit, and Ann Arbor in Michigan. Finally, it will end in New York by a screening at The Ukrainian Museum.

With the exception of Columbia University and Philadelphia, all other screenings are going to be attended by the director himself. Additionally, the screening at The Ukrainian Museum will be attended by Anton Sviatoslav Greene, who plays the principal role in the film, that of the boy guide.

So that’s one way, but we don’t see this celebration as confined to a specific one project. We’re going to celebrate it every time we screen films. We have an ongoing film series in Philadelphia this year with three screenings planned in addition to “The Guide” and we are in conversation with other potential venues where we are going to be bringing Ukrainian films as well. Basically, it’s an open-ended celebration.

What do you see as the role of this club in the near future and what projections would you make for the next 10 years?

Ideally I would like for some kind of a sponsor to materialize with enough money to make the club into an institution. We are now one of the biggest collections of Ukrainian films outside Ukraine, and we sit on a treasure trove of Ukrainian cinematographic legacy. For a number of reasons, we cannot be a lending library; we cannot even allow people who are interested in Ukrainian film to watch them outside our regular screenings, and I don’t think that’s right.

Ideally I would love for our film club to develop into a research outfit and provide open access to all the films. If there could be a film librarian who could catalogue the films, cater to those who would like to use, describe and study them and what-not, that would be fantastic. That would be in addition to spreading the geography of our screening and engaging more film platforms from other institutions into the sphere of Ukrainian filmmaking. That would be the next step.

Can you explain what you mean by “Ukrainian national film”?

|

| Polish film director Krzysztof Zanussi, a long-time friend of UFCCU, speaking on the Ukrainian Euro-Revolution at Columbia University, February 7, 2014. |

At the time we started, the club was keenly aware of the intellectual and cultural discussions underway in Ukraine in that time: “What is a national film?” One could hear loud voices of people advocating a redefinition of Ukrainian film away from what is logically implied and in sync with the way the French national film is understood, or American or Polish. Those people were actively trying to impose on all the rest of Ukraine a colonial concept of Ukrainian film as something purely geographic.

I was once present at a press conference when one of the leading such proponents, Andrii Khalpakchi, who has for years headed the Ukrainian international film festival, Molodist, said, “Every film that is made in Ukraine is thus Ukrainian.” That was exactly the kind of colonial vision of Ukrainian film, but also “Ukrainian culture” that we wanted to undermine, deconstruct, expose as essentially colonialist, as perpetuating the old patterns of enslavement and cultural control of Ukraine by Russia. We instead propose and promote an understanding of Ukrainian national cinema as made by Ukrainian film talent (directors, writers, actors), in Ukrainian, based on Ukrainian story and with primarily a Ukrainian viewer in mind. A film that would be a reflection of our culture, historical experience, language. A film that would give the voice to the people and help them express themselves. This understanding is very much is on par with how national films are viewed in the USA, France, Russia, Poland, Israel and many other countries.

We started broadcasting that message both in the United States where we had, of course, a very limited audience, but also in Ukraine, where we also became known almost from day one, thanks to the enthusiasts in the Ukrainian filmmaking community who thought we were doing a very good job. As the Club’s director, I was featured on several television programs and I voiced those ideas consistently. Every time I went to Ukraine, I sought forums to voice these ideas, which were then walled off by entrenched Ukrainian film-making establishment that was supported by the oligarchic money. They had all the support of the richly financed television production studios and companies like 1+1, Inter, ICTV and whatnot.

I remember the great enthusiasm with which the filmmaking students at the Karpenko-Karyi University reacted to my lecture on what national film is, because that gave them a new understanding, not only of film, but of their own purpose and vision of themselves as future professionals. The lecture was supposed to be an hour and a half – it lasted for three hours because they kept asking me questions, and we kept talking.

How else does the club contribute to the field?

|

| On the road with “The Guide,” Ukraine’s official entry for the Oscars. After screening at Wayne State University, Detroit, MI; director Oles Sanin (holding the poster) and lead actor Anton Greene, December 10, 2014. The last stop on a six-city tour conceived and co-organized by the UFCCU. |

Our Internet website has been the only English-language Internet resource on the Ukrainian film. I don’t know of any other. There are Russian-language resources on Ukrainian film, Ukrainian-language, Surzhyk-language on Ukrainian film, but no English-language websites even remotely similar to ours, however modest ours might still look. This remains a very important presence on Ukrainian film on the World Wide Web.

Secondly, I also thought and felt the interest of our audiences not only in the films that are produced in Ukraine, but also how filmmakers of other countries viewed Ukraine in their films. So we very early in the day introduced a special series, “Ukraine through the eyes of the world,” within which we started screening films that showed Ukraine, and not necessarily in a positive way. Very many films show Ukraine in defaming, racist sometimes, sometimes very stereotypical or colonial manner. Most of the films, that we have, offer a positive and very often unexpected view of Ukraine and that is thought-provoking for our viewers because it’s always interesting to take a new perspective on something that you think you know.

Also I tried to encourage my students to think of Ukrainian film outside their immediate academic program and get them interested in reviewing the films and, in that way, providing something that the Ukrainian filmmakers dramatically lack: feedback from the international community on what they’re doing. Because Ukrainian film criticism in Ukraine is still very underdeveloped and Ukrainian criticism outside of Ukraine simply doesn’t exist. Everything that these self-appointed, or enthusiastic film reviewers do – which they often don’t realize – is number one, a huge source of inspiration for Ukrainian filmmakers. To know that somebody in New York or in the United States, not only watches your film, but thinks about it, and produces a coherent criticism, is hugely inspiring. It also creates almost automatically, the kind of perception that you are functioning not in the stifling world of Ukrainian filmmaking, where you depend on the mood of a deputy minister or a director or an oligarch, but suddenly you feel like you’re part of the larger international film-making community.

To make Ukrainian film more easily accessible to the rest of the world we initiated a subtitle-translation workshop. When I announced there was an incredible reaction from people from all around the world. I had responses from the Czech Republic, Poland, Ukraine of course, England, the United States, Canada. Everybody just wanted to participate in translating Ukrainian- language films into English for free. We generated subtitles and supplied with subtitles quite a number of important films. Then we started also cooperating with a very important, the biggest Ukrainian film archive actually, the Oleksander Dovzhenko Center in Kyiv.

I understand the club still collaborates with the Dovzhenko National Film Center.

This cooperation became particularly fruitful with the arrival of the enthusiast of film preservation and Ukrainian film, Ivan Kozlenko, a young Ukrainian-speaking gentleman from Odesa. Before even becoming the director of that center, he organized the unprecedented Ukrainian silent film festi-val in Odesa called the Mute Night (Німа ніч). It was supposed to be a pun: the mute culture, which is Ukrainian, and the silent film. And he openly declared that one of the purposes of that festival was to re-appropriate the gems of Ukrainian silent film that were made in Ukraine with Ukrainian talent, but have been appropriated by Russian imperial culture and presented to the rest of the world as Russian.

Needless to say, that kind of declaration of purpose appealed to me. He invited me to participate in the festival, to be one of the guests, and then we started very closely cooperating, becoming a conduit here in the West for these films, to re-inject them into international circulation. Every now and then I get letters from different libraries asking me where to find this film collection, and I’m only too glad to channel their enquiries to the Dovzhenko Center.

Wait, you disagree with Khalpakhchi when he says all films are Ukrainian, yet you agree with Ivan Kozlenko who’s trying to reclaim films made in Ukraine. How do you explain this?

Two different realities: Kozlenko meant films made in Ukraine with Ukrainian talent, like Vira Kholodna, a woman who was born in Poltava and moved in her childhood to Moscow but then again came back to Ukraine and had a husband who was Ukrainian and could plausibly be also thought of as a Ukrainian in the traditional sense of the word. Films made in Ukraine by Dzyga Vertov with Ukrainian sensibilities, featuring Ukraine, using Ukrainian material. That’s something that I agree with; that’s not the geographic understanding of identity, it’s the essential understanding of identity, identity built on features that are essential to any identity.

Whereas for Khalpakhchi, the reality today is geographical identity, encompassing films that are made for Russian television, the Russian film market, with the Russian consumer in mind, with Russian spectator in mind, not only that, the films that would deliberately be cleansed of any visual or audio cues that might place them in Ukraine because, “Russian viewers are irritated by such cues.” So those films are not only not Ukrainian, but they are in a sense anti-Ukrainian and to instill the notion of such films as being Ukrainian national cinema, to me, is deeply colonialist by its logic.

Now there is a necessity, a kind of imperative to clear the water and outline, articulate an understanding of what it means for a film to be a national film.

Does this stance not come from a position of defense? Is Khalpakhchi perhaps not afraid that there is no Ukrainian cinema, so he wants to grab whatever he can?

No, that’s not quite the situation. The situation is that such a view is used to siphon what little money there was for Ukrainian filmmaking into Russian projects. And that’s unacceptable, given the dearth, the chronic dearth of Ukrainian film that compels many film commentators to say that Ukrainian film has been in a state of coma for decades. It even serves to justify that situation and to give the money that is at a premium to the films that have nothing to do with Ukrainian national film or to giving voice to Ukrainians and their stories.

What is going on in Ukrainian cinema today? How has the Maidan and the sub-sequent war affected the arts, the cinematic arts in particular?

What’s going on in Ukrainian film is exactly what was going on up until today: nothing’s changed, really. What has happened is nothing short of absurd. Under the repressive regime of Yanukovych, the Ukrainian film industry was much better funded. There was something to the tune of 250 million hryvnias allocated for filmmaking, an unheard of sum of money. Even though the Ukrainian agency for film was adhering more to the Khalpakhchi conception of national film than to my conception of film, in between some films with Ukrainian attributes were made.

Now that same agency is headed by Mr. Pylyp Illienko, the son of the Ukrainian film classic, Yuri Illienko. He has a vision, the energy, dedication, and a sense of mission, but what he doesn’t have is money. He has zero budget and the new Ukrainian government is very similar to all the previous governments in one essential sense: culturally it’s not Ukrainian. It looks at the culture, at best, as something of a bother, something that has no consequence, something that has to be marginalized lest it be allowed to distract you from things more important.

Of course, they’re fighting a war, but the war is also waged in information and culture. There has always been war in Ukrainian filmmaking between the Moscow agents of the influence and those who believe that Ukraine is entitled to have its own film and its own expression in film. Paradoxically enough, the proponents of the colonialist film oriented toward Russia, culturally Russian, have been particularly vocal since the Maidan. The other obvious tendency is for them to pretend that nothing happened, that no revolution happened, that dignity was not the center of that revolution. They continue to churn the films that are indistinguishable from Russian products – language-wise, message-wise, by their consistent ignoring the sensibilities of Ukrainian public.

They are using the Ukrainian willingness to accommodate the Russian-speaking part of the country as license to stay the same, as license to justify the unjustifiable state of things where the entire information space, media, distribution of language programs and everything else, are formatted in a way so as to facilitate a very rapid Russification of society. By Russification I don’t only mean linguistic Russification. Linguistic Russification always brings in mental Russification, the appropriation of suprematistm, messianic program and moral values, that are not Ukrainian, but Russian, and are very often antagonistic and inimical to Ukrainian values.

There’s this mantra, though – you see it a lot in feminism – that the nation must come first, and then we can talk about feminism, or women’s rights, or equality. So first we have to save Ukraine as a sovereign nation, and then we can talk about making movies, right. If Ukraine loses the war that Russia has waged against it, there will be no Ukrainian cinema, so how do we reconcile these two issues?

There’s nothing to reconcile. Making Ukrainian films is a powerful way of mobilizing the Ukrainian nation all across the board. Appealing to things Ukrainian as infinitely superior as values over the values of the aggressor is a powerful mobilizing force. Even Stalin in his day of war against the Nazis, knowing the incredible power of nationalism, allowed for nationalist expression in film, encouraging such of his court filmmakers as Ihor Savchenko to make “Bohdan Khmelnytskyi,” Mikheil Chiaureli to make a film that appealed to Georgian nationalism called “Georgi Saakadze.” Now, to deny Ukrainians – is not simply stupid, but suicidal. There is no conflict between making films and surviving as a nation. In fact one thing helps the other.

In your opinion, what is the most exciting thing happening in Ukraine today? In any sphere, cinematic or otherwise?

Well, I belong to the definite majority of people who treat what’s going on in Ukraine as singularly a war of aggression; therefore, it’s difficult to find anything exciting about war. Ignoring that, what is exciting is the long overdue process of crystallization and consolidation of the national identity in Ukraine. There is a kind of emerging national unity that we haven’t had, at least we hadn’t had the feeling of it before. Maybe it was there, but it took this war and this atrocious behavior of the formal imperial power who refuses to become former but wants to be future and present imperial power to give Ukraine a sense of purpose as a nation, a sense of solidarity as a nation, a sense of shared values as a nation. For me – though I would object to the word “exciting” given the war – had there been no war, that would be very exciting.

Ali Kinsella is a recent graduate of the interdisciplinary Slavic studies program at Columbia University’s Harriman Institute. The original version of the interview appeared in two parts in The Ukrainian Weekly, November 30 and December 7, 2014 issues No. 47 and 48).

|