February 9, 2015, New York, N.Y. |

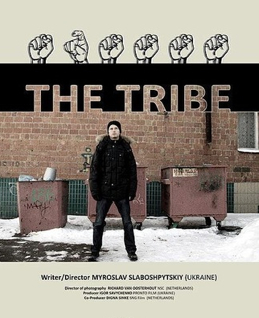

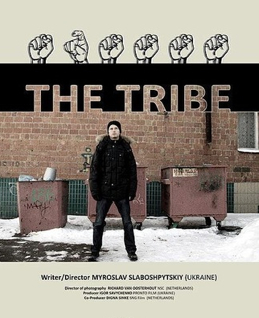

Critics Sound for Slaboshpytskiyi’s The Tribe |

| |

|

| Yana Novikova and Hryhorii Fesenko, lead actors of The Tribe. |

Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy’s The Tribe is perhaps the most-talked about Ukrainian film since independence. More importantly, it has been the most internationally decorated film by a Ukrainian film director ever.

Director’s short bio. Born in Kyiv, Ukraine in 1974, Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy graduated from the filmmaking department of the Ivan Karpenko-Kary State Institute for Theater, Film, and TV as a feature film director. He has worked at the Dovzhenko Film Studio in Kyiv and the Lenfilm Studios in St. Petersburg, Russia. He has also worked as a script writer for numerous made-for- TV movies and published a number of short stories. One of them, “The Chornobyl Robinson,” took first place in the All-Ukrainian Script Contest Coronation of the Word in 2000. His debut short, “The Incident,” competed in about 25 festivals in 17 countries. His second film, “Diagnosis,” was nominated for the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival. His short, “Deafness,” was his second Berlinale submission and also got a Golden Bear nomination. In the autumn of 2010, he received a grant from the Hubert Bals Fund of the Rotterdam Film Festival for the development of his first full-length feature film. In 2012, Slaboshpytskiy won the Silver Leopard at the Locarno Film Festival ’s “ Pardi di domani ” competition for his film “ Nuclear Waste .” This short was also nominated for an EFA Award in 2013. His latest film, The Tribe, won over thirty festival prizes, including an unprecedented four at the Cannes International Film Festival, among them the Nespresso Grand Prize for La Semaine de la Critique in 2014. Collected here are reviews written by students at Columbia University in the City of New York: Katherine Floess, Clemens Guenther, Anna Kaplan, Kelsey Piva, and Ani Poghosyan.

* * *

The Tribe bears much resemblance to other films; in fact, it seems quite similar to chernukha [Also known as “dirty realism” in English, this refers to a genre popular in the former USSR since the 1990s that shows society’s dirty underbelly. Ed.] films: with an interest in realism, to the point of trying to show the characters actions’ in real time, and absolute candor with regards to the scary, dangerous, and violent aspects of life. In this respect, The Tribe is not original, and, even—if you have seen other films with similar stories—not all that shocking. But these aspects—the storyline of the film and the action of the film—are secondary to its main conceit: that it is presented completely in Ukrainian sign language with no subtitles.

Since the director, Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy, made the choice (and a very strong choice) to not present the film with subtitles, I think the viewer is forced to consider why he made this decision. (Indeed, I think this choice, more so than every other shocking moment in the film's story, is omnipresent when thinking about the work—a fact disturbing in and of itself.) Judging from the film’s release and distribution, I think it is safe to say that the film was not meant for the deaf community. This decision lends a voyeuristic aspect to the work: the characters are (literally and figuratively) voiceless. There is also a primitive aspect to the film—as its title might suggest. We are analyzing the characters’ behavior and trying to piece together their perspectives, much as a biologist might try to piece together the interactions of animal subjects. In this respect, I found the ideological choice, while daring, a little bit uncomfortable.

Speaking generally, sign language is very beautiful, and this beauty is well suited for capture on film. By not using captions, the director does seem to be aiming at demonstrating the extreme visual power of film. In this respect, he is exploiting sign language as a very convenient way of challenging the boundaries of cinema’s capability as a visual medium above all; suggesting that a lack of sound or language does not in any way limit a film. This choice of using sign language to make this aesthetic point left me a little uncomfortable about the film. Sign language is, after all, a real language with meaning, not just something beautiful to look at.

However, I do not believe the director was trying to present his subjects as anything other than human. By leaving out the subtitles, I think the director was also trying to locate the shared aspects of human life and growing up (violence, love, death, [aborted] birth), within the very alienating effect of the language gap. The characters are all presented with agency, and the film did not seem to be trying to create “pity” for its subjects. To me, it made a difference knowing that the actors were, in fact, deaf. The film’s conceit doesn't necessarily require the actors’ to actually be signing in a coherent way (since, as I mentioned, it doesn't seem to be aimed to the deaf community)—but I assumed as a viewer that the characters really were having real conversations. Thus, they didn’t lack language; I just lacked the knowledge to understand their language. This distinction, for me, made a huge difference in respecting the film.

But the choice of not including subtitles did, I feel, limit the capabilities of the film. The characters, who can speak among themselves but must also travel in a world that does not understand them, learn to interact with an aural world, and the film demonstrates very well how certain things do not require linguistic communication. The deaf students can get around quite well in the hearing world as prostitutes and thieves; sex and violence can be understood without language—we don't need any words to understand the definitive conclusion of the film. This is fairly straightforward, but I think the film is interesting more for what it cannot express than for what it can. Certain aspects of life for these “students” are dropped fairly quickly. We see them spending more time beating people in a park than learning in the classroom. While this speaks to the world of the characters, it also reflects the limitation of the film’s conceit: it had to be about violence and sex to make any sense (and hold any interest) without language. How would viewing the film be different if you did understand the sign language in it? The Tribe is interesting not for what it does show, but for what it can’t. If we can understand this story without any language, what is language for?

Katherine Floess, USA.

* * *

Without Words

|

| Myroslav Slaboshpystkiy, the enfant terrible of Ukrainian film today. |

When public safety and order break down, the weakest in society suffer most. If the breakdown of public order continues for about 25 years, people start to return to archaic life. This is exactly what has happened in the post-Soviet space. Such a return can find expression in more harmless ways like a barter economy or the reinforcement of family structures, but it also has its dark side: violence, rape, and theft. Since Steven Pinker we know that the archaic times were not the times of the noble savage but followed rather the Hobbesian model of “man as man’s wolf.” Violent tribes robbed, raped, and ravaged.

Russian directors have developed their own genre for filming this development and its heyday was in the Russia of the early 1990s. This genre is called chernukha (from the Russian word cherno, black) and shocked the audience in the East and then West with its brutality and its ruthless candor about social injustices. The Ukrainian director Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy has now contributed another shocking movie to this tradition.

Slaboshpytskiy's brilliant idea was to make a film in a boarding school for deaf and mute youth, using only sign language: no music, no dialogue, only noises. The viewer cannot hear what the characters say, but she can see what they do. Most impressive is probably the scene that portrays a backroom abortion, and a young prostitute uncontrollably cries and screams. People can’t speak, but they can scream. The absence of noises makes everything more horrifying. The scenery of the film calls to mind a Chornobyl-like lunar landscape with its abandoned shacks far from civilization. The state and social institutions have long ago withdrawn from that place. Now, young gangs and ruthless pimps dominate the school. They establish a regime, where every man is to himself. The boys become bullies, the girls, prostitutes.

It is not the plot that is innovative in this film. The story of a clueless boy entering and adapting to a new, inhospitable environment has already been told many times. The best example for the Russian context is probably Aleksei Balabanov's classic Brother (1997) about the gangs in St. Petersburg in the 1990s. Neither is the depiction of life in homes for the disabled in the post-Soviet space new, nor the description of the brutal reality of rape and violence there. (Mikhail Elisarov's novel The Nails tells about that for instance).

The strength of the film lies in its style, its slow camera work, its slow way of telling the story. Although the viewer quickly anticipates what will come next, the film never becomes boring or predictable. This is not least due to the brilliant actors. Hryhorii Fesenko, a young Ukrainian actor, makes his fascinating international debut playing the deaf and mute hero Serhii, the only character the viewer can feel any sympathy for. Serhii develops from a clueless, shy boy entering the boarding school at the beginning of the film, to a violent and determined young man over the course of the film. Although the whole plot is described only in sign language, Serhii’s facial expressions present the full range of human emotions: joy, hope, anger, despair, and lust.

Another upcoming hopeful actress is Yana Novikova, who plays Anna. Serhii is attracted to Anna and they have an intensive affair. The sex scenes in the movie are pretty explicit and may shock some viewers, but the film benefits from them. Anna, who is presented as a joyful prostitute in the first half of the film, experiences love and tenderness for the first time. But anyone who expects a happy ending is bitterly disappointed. Not only will Serhii force her to have sex with him, she will also learn that she is pregnant. The following scenes of the film are the most impressive and the most shocking ones. Yana Novikova at her best portrays all the despair that comes suddenly to a young girl who has been living as positive in a misanthropic environment.

The Tribe reduces man to his elementary condition, to his will to survive. People try to survive, but there are no goals anymore, nothing is left, for which it could be worth surviving. The Ukrainian post-Soviet condition comes to light in all its desolation and hopelessness. The Tribe contains a warning: If no one cares for the weak and the powerless, if no one cares about civilization anymore, then we will become animals. It is not the first warning of its kind. And it is not the loudest one. But it is so far the most impressive.

Although the film hints at many features specific to the post-Soviet space, its messages reach beyond that context. At first sight, the characters and their problems seem to be far away from the Western world. But haven't we heard of abuse and violence in German or American boarding schools as well? Apart from the social background, the film also touches philosophical questions: What are the origins of violence? What role does the environment play in the emergence of violence? And is there any way out?

It remains unresolved, whether the boarding school is a separate world with its own rules or if the film claims to portray a more pervasive social or human condition. One could imagine breaking news shows on television warning against armed psychopaths walking around the country. But the voyeuristic perspective from outside doesn’t fit the complex conditions of violence and personal development. There is no psychological or physiological precondition for violence; it is all about the environment. And it is the task of the whole society to avoid slipping back to archaic times.

Clemens Guenther, Germany.

* * *

|

| Many draw parallels between the microcosm of The Tribe and Ukrainian society under the Moscow puppet regime of Viktor Yanukovich. |

Even though not a single word is spoken over the 130 minutes of The Tribe, walking out of the movie you feel like you have been yelled at and punched in the stomach. Over and over again.

The movie follows a teenager as he arrives at a boarding school for the deaf. We watch him go from an insecure newbie trying to fit in with the cool kids, to one of the leaders of this gang that is “the Tribe.” Step by step we are led deeper into the dark world of the tribe, learning that the school setting is just a backdrop. Every night, the two adolescent girls are taken to a local truck stop to sell themselves to the truckers. One of the gang leaders is there as their pimp to handle the financials, but also to protect them. The long scene of the girls changing in the van on their way to the truck stop leads us to question: Who are they hiding from? This question stems from the complete lack of adult supervision throughout the film. We quickly learn that the adults are even more corrupt than the teens, facilitating prostitution and violence.

As we watch the gang fight, the young kids being robbed and shaken down for their last penny, we realize that respect for property, privacy, and human lives is absent. Our main character rises to his role as a pimp and his position near the top of the chain of command until he falls in love. It is difficult to distinguish his love from his lust. His first interaction with this girl comes when he walks in on her naked on his first day as a result of a prank. From here, he becomes obsessed with her. He pays her for sex, and their first intimate encounter starts as an alienated and impersonal act, but turns into a passionate love scene. The boy falls even more in love (or lust?) with the girl. He continues looking for ways to pay her; although it is not clear whether she wants his money, she is definitely taking it. His love interest causes him to lose his spot in the gang’s hierarchy as he becomes increasingly obsessed with this girl and isolated from his gang. He ends up stealing and even killing to pay her for sex (or perhaps her abortion, shown in graphic detail). His breaking point is provoked by his broken heart. As the movie comes to an end, we watch him, cold and methodical, take his revenge. The feeling of doom invoked by his victims’ inability to hear him coming is paralyzing.

Yet, this account of the plot is mostly based on guesses. The distress of not understanding for sure what is going on forces the viewer to invent the plot to the point where she feels she, in fact, does understand everything. In this way, we are left to realize how patronizing we are in our assumptions about segments of the society that we simply do not understand.

From the first moment of the movie, the viewer feels like an outsider looking into, even peeping on, a very closed community of deaf people. The first impression that the subject is a school for deaf children turns into a thought that this is a boarding school for all ages. When it becomes clear that the teachers are deaf as well, and shown outside of school, you start wondering if this is an imaginary community where everyone is deaf. Only far into the movie, when a couple of policewomen talk, do you realize that this is a community within contemporary society. It makes you wonder where this guy came from. Who is his family? Did they not want him BECAUSE he was different, and is that the case for all the members of the Tribe? This realization forces us to take responsibility and acknowledge that the blindness of our society allows for Tribes such as this to exist and very much be real.

The Tribe can be compared to a movie in a foreign language without subtitles or voiceover. But the truth is, it is nothing like that. The presence of a foreign language at the very least would add an element of sound distraction; by the end we would probably even recognize a name or two. Here, however, the silence is deafening. You are left alone with your thoughts and you have to face yourself and what is happening on the screen. Since your eyes are your only tool for deciphering the story, it is impossible to look away—the noises are circumstantial and insignificant, giving no indication when one scene ends and the next begins. The ear is almost neutralized, turning the tables on hearing people, who are forced to rely on their eyes alone and must feel what it’s like to be deaf.

Immersed in the annoying noises of mundane things like footsteps, plastic bags, and car engines, which are amplified by the ambient silence, the viewer is provoked to concentrate on trying to decode the dialogues, the characters, their motivations and relationships. Yet all one is ultimately left with is the unbearable silence of the violence, exploitation, and indifference of the community that is the Tribe. The juxtaposition of extreme alienation caused by the silence and inability to understand the characters (we don’t even know their names!) with the incredible urge to comprehend what they are saying and relate to them creates a tension that makes this movie a difficult one to shake off.

This film is a punch in the stomach, a bold statement shaking the viewer to wake up and think beyond her narrow world; think about the different. It reminds us of the consequences of neglect, marginalization, and indifference. But it also reminds us that perhaps we are beyond the point of repair. That because everyone is to blame, and everyone is responsible, nobody is.

Anna Kaplan, Israel.

* * *

|

| Many draw parallels between the microcosm of The Tribe and Ukrainian society under the Moscow puppet regime of Viktor Yanukovich. |

Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy’s film is a raw depiction of life at a boarding school for deaf teenagers. The film follows Serhii as he navigates gang initiation, sexual awakening, and psychotic rage. The Tribe is a movie about meaningful absence and masquerade.

The absence of a spoken language challenges viewers’ thematic interpretation. The audience must understand the film as a type of ballet, with sign language acting as a performative mime. Viewers become intensely aware of sign language’s expressivity—how a character’s intention can change the meaning of her gesture. The absence of words forms a more intimate relationship between the viewer and the characters. By choosing not to include subtitles, Slaboshpytskiy gives viewers authorship over the film’s plot. There is freedom for the audience to create a personal synthesis between the characters’ gestures and their associated meanings or ideas.

The absence of verbal cues also brings to question the importance of those sounds that are represented in the film. The hollow sound of punching in a gang fight, and the cries of pain during an abortion become much more horrifying when presented against a silent backdrop. In this sense, the film is hauntingly poetic.

Perhaps even more hauntingly poetic is Slaboshpytskiy’s use of masquerade. He often disguises events and characters within one another, like a nesting doll of identities. For example, the movie begins with the celebration of the first day of school; however, viewers quickly find out that the celebration serves to distract from the school’s underlying corruption and violence. We see this type of distraction throughout Russian history—Catherine the Great staged masquerade balls during the Russian-Turkish wars and even the Sochi Olympics distracted from Putin’s imperial regime. [It should be pointed out that, while the example stands, Ukrainians’ experience of these Russian dictators is marked by significantly different historical events. Ed.] Slaboshpytskiy continues this tradition of distraction by creating characters that vacillate between victims and aggressors, making it difficult for the audience to completely empathize or accuse a single character.

As an allegory for current events in Ukraine, The Tribe seems to suggest that events are not always as they seem and it is important not to abandon a nation left without a voice.

Kelsey Piva, USA.

* * *

A Silent Blow to the Head

Masterfully performed in sign language and void of subtitles or voiceovers, Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy’s The Tribe is, however, bursting with dialogue. It is an intense deluge of uncanny adolescent chaos, teenage delinquency, bare honesty, fervent love, and extreme hate. The “language” of the characters is surprisingly clear and comprehensible.

A tongue-tied shot of a bus stop—the film’s opening scene—introduces a teenage boy who is looking for directions to the school for the deaf (let us call him Serhii). One should be careful in presenting Serhii as the complete protagonist. Rather, he is more like the “white rabbit” that will lead us into the “hole” of the deaf adolescence of the school, our silent guide. In fact, the viewer’s point of focus shifts from one character to another as the camera steadily treads behind the characters. The line between protagonist and antagonist is blurred.

The bus stop scene, in fact, combines many of the film’s common elements. From across the street, one notices the languid movements of those waiting. This delineation of distance and detachment is continued throughout the film: there are no close-ups, almost as if the camera knowingly denies us a private, sympathetic perspective, forcing us instead to act as silent, unhelpful observers. This can be frustrating and one might want to break this distance and assume the perspective of the soundless, impassioned characters, but the camerawork maintains the careful distance and imposes the impossibility of association. Furthermore, the characters’ posture and mannerisms suggest that they don’t want us to be involved or to sympathize with them. With his camera, cinematographer Valentyn Vasianovych imbues the characters with vehement independence, and an attitude of self-sufficiency. They let down their guard on occasion, but usually unexpectedly, unintentionally: the graphic scene of a teenager’s back-alley abortion cuts through the screen and makes the viewer wince; the physical pain and brutal openness come through as the young woman is laid before us in an extremely vulnerable state.

This vulnerability of the characters, furthermore, is the underlying reality. Through their gesticulation and poise, the characters, in fact, depict the opposite, completely denying their vulnerability. We see them seemingly easily maneuvering through life; they are fast, capable, extremely adaptive, and far from naïve. They are our all-knowing guides into their cruel world, and watching them one feels incapable and clumsy. But there is a hidden realm of unforeseen dangers that exclusively await the deaf youth, such as not noticing a truck approaching, not hearing someone creeping from behind, staying soundly asleep when your friend is being brutally murdered next to you. Slaboshpytskiy unsparingly shows the unanticipated vulnerability of their reality.

The film offers us a gradual access into the school and the world these teenagers inhabit. The initial scenes show the first day of school ceremony, depicting a friendly, peaceful atmosphere within the background of tinkling bells as the headmaster and the parents along with the students march through the doors of the school. Here, again, the camera is positioned behind a glass door, observing from a safe distance.

Serhii is freshly enrolled and we see him first timidly enter a classroom. Initially he is bullied, the torment growing until Serhii is “initiated” into the group. This entails a gradual progression of delinquency and crime, from prostitution and robbery all the way to brutal beating and murder. The lens of naivety and innocence with which Serhii is initially depicted gradually evaporates as he enters this silent hostile world of deaf teens. We also see Serhii falling in love, as unlikely as it might have seemed. His teenage impulsiveness clashes with his relationships and the rules of the “tribe.”

The film emits a sense of eerie terror and heaviness, which consequently escalates toward the final scene of midnight horror. There are no screams or struggles as a horrendous crime is committed with a certain indifference. The camera steadily follows the perpetrator, as if in a daze. This time the viewer is somewhat grateful for the distance placed between the camera and the characters and the superficial perspective and remoteness of the protagonist.

Overall, the film is eerie, both in sound and color. There is an overcast, cold September atmosphere, that is only broken from time to time with a pop of background color that could be understood metaphorically: the graffiti-covered wall behind the young men marching towards a fight might suggest their youth in contrast with the maturity that they so feverishly try to depict; the love-making scene against the backdrop of a strikingly blue wall can be deemed a sudden “awakening” of emotion. Furthermore, the color depicts poetry, like a sort of renaissance painting. Vasianovych shows complete mastery of perspective, uniquely adapting artistry to the storyline.

Another noteworthy aspect of the film is the remarkable sound design. The ordinary sounds of the atmosphere go deeper than any dialogue could and are uncomfortably emphasized because of the lack of spoken sentences. This film leaves a stain on the consciousness. Once it is over, one subconsciously becomes more aware of mundane sounds: the screech of a door when exiting a room, the sound of footsteps on the floor, breathing, the ruffling of clothes on the body.

The Tribe is a masterpiece akin to an unsparing, unexpected, inaudible blow to the head.

Ani Poghosyan, Armenia.

For more information on The Tribe.

Tribe will be screened at the MoMA in its festival New Directors. New Films in March, 2015.

Clip of The Tribe. |