Poster Politics: The Art of Revolution

Benita Stambler Empire State College, State University of New York |

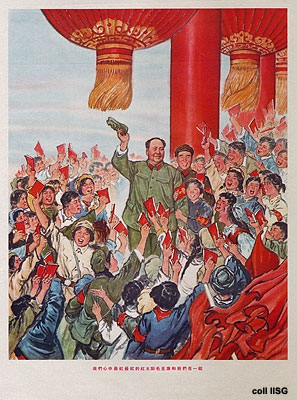

This one-lesson unit examines Mao Zedong as a revolutionary leader through Chinese propaganda posters from the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, 1966-1976. Both beautiful and powerful, these posters offer students a window on the cult of personality surrounding Mao and its place in the broader context of the Cultural Revolution. The lesson contains student readings and activities as well as introductory materials for the instructor and teaching strategies. It can be used either online or in the classroom.

Major themes of the unit:

- Mao’s place in modern Chinese history and society

- The Mao personality cult

- Art and politics during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution

- Political posters as historical sources

This material could be useful in a variety of undergraduate courses including but not limited to:

- Modern world history

- Chinese history and society

- Asian history and culture

- Art history and visual culture

- Comparative politics/political science

- Sociology (especially mass movements)

The unit is designed to be used with the online resources found on the pages for Mao Zedong and Other Leaders.

Suggestions for using the unit:

- Posters from other places, e.g., posters of Roosevelt from the U.S. or European recruitment posters from World War II explain that political posters were a useful tool in many cultures.

- Combine posters with primary and secondary sources on Mao Zedong and the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

- Posters of Mao with adoring crowds can be viewed alongside photographs of Mao’s public appearances.

Mao Zedong and the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution

See also the Mao Zedong timeline. For more background information on the Cultural Revolution, see also the “Instructor’s Introduction" in the ExEAS unit China’s Cultural Revolution.

Mao Zedong is remembered as the father of China ’s communist revolution, and he presided over what amounted to a series of revolutions in modern China. Mao was the leader of the Communist forces when they triumphed over Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists in 1949 to form the People’s Republic of China. As Chairman of the Communist Party in the 1950s, he spurred on the Chinese people in the pursuit of economic revolution under the banner of the Great Leap Forward. And in the 1960s and 1970s he sought to remake Chinese society and culture yet again by ridding the nation of traditional elements and urging the country’s youth to pursue constant revolutionary struggle in the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

The Cultural Revolution had at least two goals for Mao. One was to restore his leadership position, which had faded in the wake of the disastrous Great Leap Forward. Another was to create a society that truly reflected his socialist ideals.

Mao believed that political revolution could only follow cultural revolution — changing people’s patterns of thinking and everyday behavior was the first step towards true liberation. Arguing that China’s cultural-historical heritage was the greatest impediment to revolutionary change, he decreed that the “Four Olds" should be smashed — old thinking, old culture, old customs, and old habits. The Red Guards took on this iconoclastic mission with enthusiasm. Schools closed, and young people were free to travel and attack remnants of the old order wherever they saw them. Teachers were vilified, artwork was destroyed, books were burned, and lives were ruined as idealistic young people sought to realize Mao’s vision of a society freed from the deadweight of tradition.

Image Courtesy of the IISH Stefan R. Landsberger Collection

http://www.iisg.nl/landsberger/

Mao was the guiding light of the Cultural Revolution. His image permeates the political posters of the period, radiating like the sun as he smiles down on China ’s grateful masses. As zealous members of the Red Guard sought to transform all aspects of Chinese life in his name, Mao was elevated to a god-like status. He became a model for the Chinese people, larger than life and said to be capable of tremendous physical feats. This personality cult ensured that his portrait or an image of his “Little Red Book," the accepted text of orthodox revolutionary thought, figured prominently in many of the posters of the period. People worked for Mao when they worked for the revolution and vice versa.

As revolutionary policy changed across the decade between 1966 and 1976, so did the depiction of Mao in the posters. These mass produced images of the great leader signaled appropriate behavior and thought in an easily understood visual idiom at a time when the entire nation was in a state of nearly constant flux and unease.

All forms of media and communication were tightly controlled during this period. Everything, from poetry to posters, had to reflect Mao Zedong Thought. Mao wrote poetry, gave speeches and produced written works that were edited and disseminated to provide guidance for almost any occasion or event.

Posters and the Revolutionary Message

Posters were an ideal means of communicating the revolutionary message to China’s diverse population. Newspapers and magazines were not of much use when addressing uneducated peasants, film was expensive, radio was geographically difficult, and live theater was available only to limited audiences. Speaking through mass produced images rather than written text, inexpensive posters were an efficient means of addressing both illiterate peasants and busy urbanites, and they were often the propaganda tool of choice. Estimates put the number of posters produced during the Cultural Revolution at well over two billion. Designed as weapons of revolution, these ubiquitous artifacts used compelling symbols to introduce new ideas, create allegiance, and inspire action.

Modern political posters were first widely used in China to mobilize the population against the Japanese in the late 1930s. In Yan’an, the Chinese Communist Party base from 1935 until the late 1940s, Mao brought together artists and presented his ideas on the purpose and methods of artistic expression. Artists were sent to the Soviet Union to learn Soviet methods. Influenced by their Soviet study and local Chinese use of woodblock prints and paper cuts, the Yan’an artists began to develop a genre of design that depicted the revolutionary lifestyle. Where Russian posters were often serious and concerned with modern industry and machinery, Chinese posters were generally sunny and bright, filled with smiling people carrying out Mao’s principles. The posters are warm and vibrant, often saturated with shades of red, an auspicious color in Chinese culture and the color of international communist revolution.

The Revolutionary Nature of the Cultural Revolution

Mao Zedong’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was not a stereotypical revolution. Revolution can be defined as a mass movement or collective action that uses violent means to overthrow a government and other institutions of society. This definition would not include the Cultural Revolution, since the Communist Party remained in power after 1976. If we look at revolution in a broader cultural sense, however, it becomes clear that the Cultural Revolution was indeed revolutionary.

Mao sought to remake Chinese culture and society, and there is little question that China was fundamentally changed during the years between 1966 and 1976. To choose the most obvious example, in a nation that valued filial piety so highly, the elevation of young revolutionaries over their teachers, elders, and parents was clearly an event with revolutionary repercussions.

In contradistinction, however, we can see that the perhaps the most important power relationship in modern societies, state control over individual citizens or subjects, was either unaffected or perhaps even strengthened during this period. We are left, then, in much the same place as Mao, struggling to understand the nature of the relationship between political revolution, on the one hand, and cultural revolution, on the other.

Mao

Cheek, Timothy. Mao Zedong and China’s Revolutions: A Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford Books, 2002.

Features a biography and analysis of Mao, selections from his most important and typical writings, and selections from secondary sources on Mao. It also contains maps, a timeline, a bibliography arranged by category, discussion questions and illustrations (including one poster).

Posters

The resources found on the Mao Zedong page and in the Further Online Resources section below provide useful background for a variety of purposes. Particularly good are Morning Sun (http://morningsun.org/images/index.html) on the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution and its visual images, and Stefan Landsberger's Chinese Propaganda Poster Pages (http://www.iisg.nl/landsberger/)

Instructors may choose to lead the entire class in discussions of the images or to split larger classes up into small groups of 4-6 students. In the case of small group discussions, students may be asked to present their “reading" of a particular image or set of images to the class as a whole during the last 20-30 minutes of class time. Or, if the instructor chooses to forego in-class presentations, each student or group might be asked to submit a short written summary of their discussion.

Viewings, readings, and discussion questions for use in class, small groups, or in online web discussions are provided below. They are divided by topic.

In addition to the specific resources listed below, use the “Chinese Posters" section of the International Institute of Social History website, “The Chairman Smiles," for these discussion activities: http://www.iisg.nl/exhibitions/chairman/chnintro.php

Propaganda

Propaganda is information or ideas that are publicly disseminated to further a particular political cause.

Viewing:

- U.S. Posters:

From: http://www.deanza.edu/faculty/williams/

- Keep These Hands Off http://www.picturehistory.com/find/p/3651/mcms.html

- Chinese Posters:

- The Chairman Smiles http://www.iisg.nl/exhibitions/chairman/chnintro.php

- The Mao Cult, Stefan Landsberger’s Chinese Propaganda Poster Pages http://www.iisg.nl/landsberger/

Readings:

- Selection from Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan , March 1927 http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1927mao.html

- Oppose Stereotyped Party Writing http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-3/mswv3_07.htm

Discussion Questions:

- American Poster Questions:

- Who or what does this poster depict?

- What message does it convey?

- How does it communicate this visually? What role does written text play? What about color and shading?

- What action does the poster want to inspire?

- Are there certain deeper values (eg. freedom or frugality) at work in the image?

- Would you call this propaganda? Why or why not? Do we have propaganda in the United States today?

- Chinese Poster Questions:

- Use the same questions listed above and add the following:

- How did Mao think the state should appeal to the masses?

- What were Mao’s rules for creating propaganda? Do you see these principles at work in the posters?

- Do you think these images would have been more or less effective in rural areas as opposed to urban areas? Why or why not?

- Comparative Questions:

- Compare and contrast the images of Mao with those of President Roosevelt. How are they similar? How do they differ?

- Which images are most appealing to you? Explain your answer using concrete detail about the posters themselves. What “works on you" and what does not?

- Do the posters use color differently? What about written text?

- Do they seek to evoke different emotional responses in viewers? How do they try to accomplish this?

Mao Zedong

This activity demonstrates how the work of others contributed to Mao’s cult of personality.

Viewing:

- Chairman Mao Inspects the Guangdong Countryside

From the Picturing Power exhibition

http://huntingtonarchive.osu.edu/Exhibitions/picturingPower.html

Readings and Audio:

- A Star Reflects on the Sun http://www.morningsun.org/red/barme_starreflects.html

- Foreword to The Quotations of Chairman Mao http://art-bin.com/art/omaotoc.html

- Every Mao from Shades of Mao by Geremie Barmé http://www.morningsun.org/red/barme_everymao.html

- Songs of the Red Guards: Keywords Set to Music by Vivian Wagner http://www.wellesley.edu/Polisci/wj/China/CRSongs/wagner-redguards_songs.html

- Songs of China’s Cultural Revolution http://www.wellesley.edu/Polisci/wj/China/CRSongs/crsongs.htm

Discussion Questions:

- What are the various perspectives on Mao presented in these excerpts? How do you reconcile these views of Mao?

- Compare the verbal portrayals of Mao with his appearance in the poster. Are they consistent?

- Compare the depictions of Mao in the Red Guard songs discussed in “Songs of the Red Guards" and “Songs of China’s Cultural Revolution" with those in the poster.

- Who was Lin Biao, and why did he write so glowingly about Mao?

Revolution

The emphasis here is on Mao’s role in leading the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

Viewing:

- The Revolutionary Committees are good http://www.iisg.nl/exhibitions/chairman/chn24.php

- In Following the Revolutionary Road, Strive for an Even Greater Victory http://home.wmin.ac.uk/china_posters/

- This Time it is Essential….

from the Picturing Power exhibition

http://huntingtonarchive.osu.edu/Exhibitions/picturingPower.html

- New Spring in Yan’an:

Image Courtesy of the IISH Stefan R. Landsberger Collection

http://www.iisg.nl/landsberger/

Reading:

- On New Democracy http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/

volume-2/mswv2_26.htm - The Character of the Chinese Revolution (from The Chinese Revolution and the Chinese Communist Party) http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-2/mswv2_23.htm (see red #5 under Chapter II)

- Some Questions Concerning Methods of Leadership http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-3/mswv3_13.htm

Discussion Questions:

- According to Mao:

• What are the necessary actions in order to mobilize the masses for revolution?

• What should be the relationship between the leaders and the masses?

• What is the role of “propaganda" in these efforts? - How can posters of Mao be viewed as “tools" of the revolution?

- How do the Chinese revolutions fit within the context of world revolutions?

- How are Mao’s ideas of revolution related to Sun Yat-sen’s Three Principles of the People (http://academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu/core9/phalsall/texts/sunyat.html)?

- Do you think that the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was really a revolution? What aspects of the Cultural Revolution were revolutionary? What aspects were not?

Leadership

These materials focus on the question of leadership. Liu Shaoqi argues that supreme leaders should provide models of right behavior, an assertion that resonates with traditional Confucian notions of moral leadership.

Viewing:

- The Reddest, Red Sun http://www.morningsun.org/red/

- Mao’s Rural Investigations in the Jinggang Mountains:

from the Picturing Power exhibition

http://huntingtonarchive.osu.edu/Exhibitions/picturingPower.html

Reading:

- How To Be A Good Communist by Liu Shaoqi http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/china/gov/what_mak.htm#How%20to%20Be%20a%20Good%20Communist

- Some Questions Concerning Methods of Leadership by Mao Zedong http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-3/mswv3_13.htm

Discussion Questions:

- What are the symbols of power and leadership in the posters? What are the principles of leadership found in these texts? Are they comparable?

- How should leaders organize the masses?

- What is the role of heroes?

- What is the role of the masses in leadership?

Poster Art

This section focuses on art’s role in revolution and politics.

Viewing:

Reading:

- Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Art by Mao Zedong http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-3/mswv3_08.htm

Discussion Questions:

- What did Mao think was the relationship between art and politics?

- What were the artistic principles espoused by Mao?

- According to Mao, how does art support social and revolutionary needs? Do you think art works this way in the United States today?

- According to Mao, how do artists get the people to understand art and literature?

- What was the role of the artist for Mao?

- Do these posters reflect Mao’s ideas or not? Explain your answer.

- Do you think these posters are successful both as art and as revolutionary tools?

Comparative Opportunities

Chinese political posters featuring Mao Zedong can be compared to posters found in other countries. Often, revolutionary leaders are used as cultural symbols. Chinese posters from the 1960s and 1970s are generally distinguished by their portrayal of Mao Zedong himself, or such symbols of the Cultural Revolution as his “Little Red Book." Using the information on “The Chairman Smiles" site, comparisons can be made to posters of revolutionary leaders of the Soviet Union and Cuba, as well as other selected national and revolutionary leaders from other parts of the world.

Viewing:

- The Chairman Smiles http://www.iisg.nl/exhibitions/chairman/index.php

- Hoover Institution Library and Archives http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives/

The Hoover Institution has an extensive collection of twentieth century political posters from around the world that is available on slides. While many posters in their collection remain uncatalogued, many others are available for educational purposes. As slides, more than 2,500 posters from the Soviet Union, more than 250 from China and more than 100 from Cuba are available, as well as posters from almost eighty other countries. Posters from the U.S., the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and East Germany are available online. - For other comparative opportunities, see the Further Online Resources section below.

Sample Comparative Activity Using Cuban Posters

This activity shows how instructors might address the question of comparative revolution through political posters. The focus here in on Cuba, but a similar activity could be engineered around Soviet posters.

Image courtesy of the Collection IISG, Amsterdam

http://www.iisg.nl/exhibitions/chairman/cub05.php

Viewing:

- The Chairman Smiles: Cuban Posters http://www.iisg.nl/exhibitions/chairman/cubintro.php

- Vietnam http://cuban-exile.com/photo/OSPAAAL/vietnam1979.jpg

- Viet Nam Shall Win:

from The Sixties Project website

http://lists.village.virginia.edu/sixties/HTML_docs/Exhibits/Track16.html

- Nixon http://cuban-exile.com/photo/OSPAAAL/nixon1972.jpg

- Lucia http://www.iisg.nl/exhibitions/chairman/cub30.php

Readings:

- The Problem of Cuba and its Revolutionary Policy by Fidel Castro

http://www.marxists.org/history/cuba/archive/castro/1960/09/26.htm - Establishing Revolutionary Vigilance in Cuba by Fidel Castro

http://www.marxists.org/history/cuba/archive/castro/1960/09/29.htm

Discussion Questions:

- Do the posters from China and Cuba depict similar kinds of revolution?

- How do depictions of Castro differ from those of Mao? How is each leader portrayed? Is there a single dominant image for each leader, or do they take on multiple roles or personalities in the posters?

- How did the Cuban artists portray revolutionary struggles in other parts of the world?

- How was the United States portrayed in the Cuban posters? Why do you think Cuban artists chose to portray the US in this way?

- How did Fidel Castro define Cuba's revolution?

- Can you see enemies of the Cuban revolution in these posters?

China

These resources are in addition to those found on the Mao Zedong Online Resources page:

The Chairman Smiles: Chinese Posters, International Institute of Social History

http://www.iisg.nl/exhibitions/chairman/chnintro.php

“The Cultural Revolution: A Terrible Beauty is Born," by Ban Wang (Chapter 6 from The Sublime Figure of History: Aesthetics and Politics in Twentieth-Century China. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997.)

http://www.morningsun.org/library/ban_wang_cr.html

Leaders and Role Models, Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington

http://depts.washington.edu/chinaciv/graph/9prclead.htm

Picturing Power: Posters from the Chinese Cultural Revolution, Indiana University

http://huntingtonarchive.osu.edu/Exhibitions/picturingPower.html

Posters from the Cultural Revolution (under Galleries) and Mao Quotes Factoid Generator (last entry under Feature Articles), Visions of China, CNN

http://www.cnn.com/SPECIALS/1999/china.50/site.map/

Visual Culture and Memory in Modern China: Images, Modern Chinese Literature and Culture

http://mclc.osu.edu/jou/visualculture/color.htm (Click on Shen, Denton and Ferry at top)

Michael Wolf Collection of Propaganda Posters

http://www.photomichaelwolf.com/propaganda/index.html

Cuba

These resources are in addition to those found in the Castro section of the Other Leaders Online Resources page.

The Chairman Smiles: Cuban Posters, International Institute of Social History

http://www.iisg.nl/exhibitions/chairman/cubintro.php

Cuban Poster Art Archive, Lincoln Cushing

http://www.docspopuli.org/articles/Cuba/CPA.html

Political Posters from the United States, Cuba and Viet Nam, The Sixties Project

http://lists.village.virginia.edu/sixties/HTML_docs/Exhibits/Track16.html

Soviet Union

These resources are in addition to those found in the Lenin section of the Other Leaders Online Resources page.

The Chairman Smiles: Soviet Posters, International Institute of Social History

http://www.iisg.nl/exhibitions/chairman/sovintro.php

Political Posters, Imants Kluss Home Page

http://www.oocities.org/imants_silent/katalogs/z_katmain.htm

Political Propaganda Posters from the Soviet Union, from the private collection of Gareth Jones

http://colley.co.uk/garethjones/soviet_articles/soviet_posters.htm

Revolution by Design: The Soviet Poster, International Poster Gallery

http://www.internationalposter.com/gallery-exhibitions/revolution-by-design.aspx

Russian Revolutionary Posters, Evergreen Review

http://www.evergreenreview.com/100/russia.html

Soviet Posters – Come the Revolution, University of Birmingham

http://www.crees.bham.ac.uk/postergallery/galleryold.htm

Other Countries (including U.S., North Korea, Germany) and General Resources

The Art of Propaganda: Nationalistic Themes in the Art of North Korea

http://www.dprkstudies.org/documents/dprk003.html

Nazi Posters: 1933-1945, German Propaganda Archive, Calvin College

http://www.calvin.edu/academic/cas/gpa/posters2.htm

Paper Trails: Exploring World History through Documents and Images:

Poster Art and World History by Marc Jason Gilbert, World History Connected

http://worldhistoryconnected.press.uiuc.edu/1.2/gilbert.html

Propaganda

http://www.propagandacritic.com/

Recruitment and War Bond Posters

http://www.haverford.edu/engl/english354/GreatWar/Mainpages/recruit.html

Trenches on the Web: Posters from the Great War

http://www.worldwar1.com/posters.htm

World War II Poster Collection, Northwestern University Library

http://www.library.northwestern.edu/govpub/collections/wwii-posters/

Andrews, Julia F. Painters and Politics in the People's Republic of China, 1949-1979. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1994.

Apter, David and Saich, Tony. Revolutionary Discourse in Mao's Republic. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994.

Barmé, Geremie. Shades of Mao: The Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader. Armonk, N.Y: M. E. Sharpe, 1996.

Chu, Godwin C. Radical Change Through Communication in Mao's China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1977.

Denton, Kirk A. “Visual Memory and the Construction of a Revolutionary Past: Paintings from the Museum of the Chinese Revolution," Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, vol. 12, no. 2 (Fall 2000), pp. 203-235.

Fraser, Stewart E., ed. One Hundred Great Chinese Posters: Recent Examples of “the People's Art" from the People's Republic of China. Images Graphiques, 1977.

Galikowski, Maria. Arts and Politics in China, 1949-1984. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1998.

Holm, David. Art and Ideology in Revolutionary China. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991.

Landsberger, Stefan. “The Deification of Mao: Religious Imagery and Practices during the Cultural Revolution and Beyond," pp. 139-184 in Woei Lien Chong, ed. China's Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution - Master Narratives and Post-Mao Counternarratives. Boulder, CO: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002.

Landsberger, Stefan. Chinese Propaganda Posters: From Revolution to Modernization. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2001.

Meisner, Maurice “Iconoclasm and Cultural Revolution in China and Russia" in Gleason, Abbott, Peter Kenetz and Richard Stiles, eds., Bolshevik Culture. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1985.

Powell, Patricia and Wong, Joseph. “Propaganda Posters from the Chinese Revolution," in Historian, Summer 1997, vol. 59, issue 4, available through EBSCO online database.

Stambler, Benita. “The Electronic Helmsman: Mao Posters on the Web." Education About Asia, Spring, 2004.

Sullivan, Michael. Art and Artists of Twentieth-Century China. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996.

Wolf, Michael; Duo, Duo; Min, Anchee. Chinese Propaganda Posters: From the Collection of Michael Wolf. Koln; London: Taschen, 2003.