Bruce Lee in Hong Kong and Harlem

|

Themes and Goals

Since the 1970s, Hong Kong martial arts cinema has transformed itself from a local Hong Kong product and obscure genre of cult-film into a lucrative transnational commodity. While Jackie CHAN and Jet LI have quickly become universally recognized film stars, the quintessential icon of “Chinese” martial arts and Hong Kong cinema remains Bruce LEE.This unit explores the seemingly universal appeal of this early martial arts film star by looking at the different tensions that exist between his reception and production on local, national, and global levels. What made this star so popular and how is it possible that he was received so enthusiastically in places as diverse as Hong Kong, Bombay, and Harlem? This question will be addressed by watching one particular famous example from Bruce LEE’s oeuvre, Jing Wu Men (Fist of Fury) and reading a variety of articles that approach the Bruce Lee phenomenon from nationalist, transnational, racial, and gendered angles.

The unit can be used to explore the following issues:

- Chinese nationalism, especially in a diasporic context (i.e. Hong Kong).

- Hong Kong cinema as diasporic cinema

- Film as a transnational medium

- The global 1960s and 1970s

- American reception of Hong Kong martial arts film

- The body, masculinity, and ethnicity

- Chinese martial arts

Audience and Uses

This unit could be used in a number of courses, including but not limited to:

- World Cinema: either as an example of Hong Kong cinema, or as a text translated from Hong Kong to other parts of the world

- Modern Chinese history, in particular in a session on Chinese nationalism

- Gender and ethnicity

- Chinese diaspora

Films

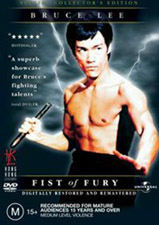

WEI, Lo. Chinese Connection/Fist of Fury/Jing Wu Men 精武門. Hong Kong, Golden Harvest, 1972. 107 mins.

Note: in the United States, this film was and still is distributed as “Chinese Connection.” However, the actual English title of the film should have been “Fist of Fury.” It is only because the canisters with two Bruce LEE films were switched that the film came to be known in the United States as “The Chinese Connection.” The film that should have been “The Chinese Connection” (in the rest of the world usually known as “The Big Boss”) was subsequently known in the United States as “Fists of Fury.” The original Chinese title of this film is “Jing Wu Men,” literally “Immaculate” (Jing 精), “Martial Arts” (Wu 武), “School” (Men 門). To avoid confusion, the film will hereafter be referred to as Jing Wu Men.To read more about the film go to: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0068767/

It is difficult to find the original version of the film (in Mandarin with English subtitles) in the U.S. Versions of the film dubbed in English are widely available for rental or purchase through retail outlets such as Netflix and Amazon.com.

Possible film clips:

While it is ideal to watch the entire film (107 mins.), for a good discussion, the following clips are essential:

- The opening sequence until the end of the titles. (From the beginning of the film to approximately the 6 minute mark.)

- The memorial service for the master, especially the moment of challenge by the interpreter and his two Japanese cronies who offer the sign “Sick Man of Asia.” (Approx. 0:09:20 - 0:17:50)

- The sequence where Bruce LEE visits the Japanese martial arts school, beats up the gathered students, and destroys the sign given to him in the previous scene.(Approx. 0:17:51-0:30:11)

- The scene where Bruce Lee visits the park and destroys the sign “No Dogs or Chinese Allowed.” (Approx. 0:30:52-0:33:57)

After the death of Bruce LEE, many Hong Kong studios sought to cash in on his popularity by making sequels of his movies using a variety of Bruce Lee look-alikes.

A. WEI, Lo. New Fist of Fury/ Xin Jing Wu Men. Hong Kong, Lo Wei Motion Picture Co, 1976. 114mins.

Jackie CHAN worked as a stunt-man in the original Jing wu men,but one of his first leading roles was in a sequel, New Fist of Fury (Xin Jing Wu Men), by the same director Lo Wei as the original Jing Wu Men. The story is set in the 1910s in Taiwan (like Shanghai, a Chinese territory colonized), where Jackie Chan transforms himself from a no-good thief into a true Chinese nationalist warrior battling the Japanese.

A signature transforming moment is found in the film when Jackie CHAN gives a heroic speech about how the Chinese should stick together and then writes the name of the martial arts school “Jing Wu Men” on his chest. This brief clip lasts three minutes (approx. 1:15:40- 1:19:25) and would be interesting to show as another example of the relationship between body and writing.B. CHAN, Gordan. Fist of Legend/ Jing Wu Ying Xiong. Hong Kong, Dimension, 1994. 103mins.

This is a remake of the original Bruce LEE film, starring Jet LI. In terms of plot, the film is quite similar to the original, but overall the film feels a little bit more Japanese friendly. For instance, in this film the hero CHEN Zhen (played by Bruce Lee in the original and by Jet Li in this remake) actually has a Japanese girlfriend. Similarly, the uncle of the Japanese love-interest is a good and wise Japanese martial arts teacher. Simply put, the film is careful to point out that not all Japanese are evil.1

Student Readings

The list below is organized by topic. Select one or two readings and gear the discussion towards the particular topic(s) chosen. Other articles can be read for background information.Hong Kong cinema as diasporic cinema

KAM, Tan See. “Chinese Diasporic Imaginations in Hong Kong Films: Sinicist Belligerence and Melancholia,” Screen 42:1 (2001):1-20.

This is a more theoretical introduction that does not address the figure of Bruce LEE specifically. However, it does get very clearly to the point of a particular brand of Hong Kong nationalism that is geared towards a motherland left behind.The body, masculinity, and film

TASKER, Yvonne. “’Fists of Fury: Discourses of Race and Masculinity in the Martial arts Cinema.” In Race and the Study of Masculinities. Edited by Harry Stecopoulos and Michael Uebel. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1997. pp. 315-336.

Adds the theme of physicality and gender to the discussion of the Bruce LEE phenomenon.Hong Kong cinema and nationalism

TEO, Stephen. “Bruce Lee: Narcissus and the Little Dragon,” in Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimension. London: British Film Institute, 1997.pp. 110-121.

Good background for a Chinese nationalist reading of the film.The appeal of Bruce Lee across national borders (especially 1970s America)

DESSER, David, “The Kung Fu Craze: Hong Kong Cinema’s First American Reception.” In The Cinema of Hong Kong: History, Arts, Identity. Cambridge, New York, and Oakleigh, Melbourne: Cambridge University press, 2000. pp. 19-43.

While not as good as Prashad in drawing attention to the political activism of the seventies, this reading is more historically informed about the actual film audiences for martial arts movies in the United States in the seventies.PRASHAD, Vijay. “Bruce Lee and the Anti-Imperialism of Kung Fu: A Polycultural Adventure.” In Positions 11:1 (2003): 51-90.

A post-modern reading which is not particularly informed about Bruce LEE, but does a very good job in providing an actual link with the political activism of the sixties and seventies.Historical background on the Jing Wu Men martial arts school

MORRIS, Andrew D. Marrow of the Nation: A History of Sport and Physical Culture in Republican China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. Especially, Chapter 7: “From Martial Arts to National Skills.” 185-230pp.

This is a historical study that actually discusses the importance of the Jing Wu Men martial arts school in China and Chinese diasporic communities throughout Southeast Asia in the first half of the twentieth century.

Student Activity: The Body and Writing

By focusing on the relationship between writing and the body it is possible to start talking about a very difficult concept, namely the appeal of action in action films. The exercise works well because it forces students to focus on and talk about particular moments in the film. (For more on the body and writing in Jing Wu Men, see Background Information for the Instructor.)Ask students to list moments in the film where acts of writing are featured.

Note: The most important examples include:(For more on these signs, see Background Information for the Instructor.)

- The sign “Sick Man of Asia”

- The sign “No Chinese or Dogs Allowed”

- “Jing Wu Men” written on the gate at the opening of the film

Discussion Questions:

- What is the significance of writing in these examples?

- What role does writing play? How does it function?

- What different kinds of writing appear?

- What do these forms of writing mean and what is Bruce LEE’s relationship with these signs?

- How do these signs set up notions of physical location?

- How do signs mark the beginning of a particular plot?

- How do you think the action of Bruce Lee’s body (and his continuous refusal to speak, but instead using his fists) interacts with the various written signs?

- Is action universally appealing and does this explain the appeal of action films such as Bruce Lee films across borders?

- Writing in contrast seems much more nationally bound. How do signs written in Chinese appeal to Chinese as opposed to those who do not read Chinese?

- What is the appeal of this film for a Hong Kong audience? A Chinese diasporic audience? A non-Chinese audience?

- Important parts of the film are shot within the main hall of the martial arts school where the dead teacher JIA Huoyuan is mourned. This hall is marked by a variety of banners sent by various dignitaries whose written phrases represent signs of respect for the dead martial arts master. If the various banners represent written signs of respect, how does Bruce Lee show his respect? Can we find other “signs” that express respect for the dead and can we interpret physical forms of ritual surrounding a funeral service as a form of body language?

Clip: where Jackie CHAN writes the words “Jing Wu Men” on his own body with blood.

(Approx. 1:15:40- 1:20:20. In the previous scene, the Japanese destroy the sign above the school. The next scene begins with members of the Jing Wu Men school beginning training.)

- What does it mean to write in blood?

- Why on his body?

Background Information for the Instructor

- The Plot

- The National Level: Chinese Nationalism

- The Local Level: Hong Kong

- Transnational Film and the Appeal of Bruce Lee Across National Borders

- The Body and Writing in Jing Wu Men

- The sign “Sick Man of Asia”

- The Sign “No Chinese and Dogs Allowed”

- The Jing Wu Men School

Jing Wu Men is set in early-twentieth-century Shanghai. At that moment in history, China was facing a variety foreign threats and incursions. The Japanese had colonized parts of Shandong and were making ever more threatening gestures in the province of Manchuria. A variety of Western, imperialist nations had negotiated extra-territorial rights in a number of coastal cities, Shanghai being foremost among these treaty-ports. After defeating the Chinese during the Opium War in 1840, the English had moreover colonized a small island off the coast of Guangzhou province, Hong Kong. By the beginning of the twentieth century, China, often referred to as the “sick man of Asia,” seemed incapable of protecting itself against these constant foreign incursions.

It is against this background of “national humiliation” that the tale of Jing Wu Men takes place. The tale begins right after a martial arts master by the name of JIA Huoyuan, founder of the Jing Wu Men martial arts school2, has died under mysterious circumstances. His disciple CHEN Zhen (played by Bruce LEE), returns to the school to avenge his murder. As it turns out, the Japanese have poisoned Jia Huoyuan because they were unable to beat the man in a fair martial arts fight. Bruce Lee takes on an assortment of Japanese martial arts masters (as well as the occasional occidental strongman) to show that the “Sick man of Asia” is indeed capable of defending itself against imperialist aggressors.

The National Level: Chinese Nationalism

As will be clear from the plot above, Jing Wu Men is filled with Chinese nationalist sentiment. A variety of symbols of Chinese nationalism and Chinese shame are brought to play in the movie. Bruce LEE physically breaks a sign reading “Sick man of Asia,” and similarly tears down a famous sign that supposedly hung at a Shanghai park, “No dogs and Chinese allowed.”3 As a concession port, the setting of Shanghai itself represents another symbol of Chinese shame and foreign aggression. Throughout the movie we are reminded that within their own country the Chinese need not expect justice from an international court. Finally, temporally speaking, the film takes place at the beginning of the twentieth century.4 As any Chinese audience would know, before long the Japanese would invade Manchuria, the second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) would begin, culminating the many years of Chinese humiliation in a struggle that would bring China independence from foreign oppression. By the end of WWII, the concessions the Qing dynasty government had granted to foreign powers had been annulled.

The Local Level: Hong Kong

While Jing Wu Men is rich in nationalist sentiment, what makes the movie interesting is the way in which this nationalist sentiment is engendered on a variety of levels — local, diasporic, and transnational. In terms of production, we need to recognize that even though Jing Wu Men is set in early twentieth-century Shanghai, it was produced in Hong Kong some sixty years later. Indeed, it is not hard to imagine how 1910s Shanghai serves as a metaphor for 1970s Hong Kong. Both places were governed by foreign powers and in both places the local Chinese population may well have felt like second-tier citizens living on occupied Chinese soil.

Hong Kong is a place where the local is directly tied both to national and broader transnational populations. After all, Hong Kong is a place of immigrants, an English colony and a harbor town where people from all over the British Empire converged. Chinese immigrants make up the largest part of its population, but these Chinese immigrants come from different parts of China — Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Beijing, to name but a few. While Cantonese speaking immigrants from Guangzhou province make up the largest part of the population, some very influential members of the cultural elite in Hong Kong are not Cantonese, nor are they able to speak Cantonese, supposedly the local language of Hong Kong.

The film industry of Hong Kong is a good starting point to understand the various strands of Chinese identity found in this former British colony. After all, while throughout the post WWII period films were made in the local Cantonese dialect; many films were shot by studios that specialized in Mandarin films. These Mandarin films were not necessarily produced by studios, directors, and actors from Mandarin speaking regions either. Many had emigrated from Shanghai after the Communists had established the People’s Republic in 1949. Simply put, films in Mandarin were often shot by people whose native tongue was arguably the Shanghainese dialect, not the standard national tongue of China.

As a result of this linguistic diversity, dubbing is standard practice in Hong Kong films. Even before Hong Kong films are dubbed into English or Chinese, the soundtrack one would hear in a local Hong Kong theater is not what people heard on the set while shooting. Simply put, there is no original sound-track to many Hong Kong films because all dialogue (as well as sound-effects) are added later.5 If the language we speak (our mother tongue) is one of the most treasured sources of identity, the linguistic confusion surrounding dubbing practices in Hong Kong points towards a complicated matrix of identities produced.

Jing Wu Men can serve as a good example of the complex linguistic politics of Hong Kong films. Bruce LEE’s native language is Cantonese. The film Jing Wu Mn, however, is a Mandarin language film. After shooting the film, then, Bruce Lee (just like all other actors) went back into the studio and recorded the lines of his character in Mandarin. It is only in his third film, Way of the Dragon, a film Bruce Lee co-produced and directed, that actors actually spoke in Cantonese.

Hong Kong films, while at least in part produced locally, moreover often draw on funding from the broader Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia, most notably Singapore. The target audience of these films, moreover, was not simply the local audience of either Cantonese or Mandarin speaking Hong Kong locals, but also consisted of a broader Chinese diasporic community found throughout Asia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, as well as the United States. Ironic but true, Jing Wu Men may be filled with “nationalist” sentiment and was enjoyed as such by Chinese audiences throughout the world; audiences on the mainland of China itself, however, did not see the film until well into the 1980s.

In short, a film such as Jing Wu Men shows that even when the plot is filled with strong nationalist sentiment, using the notion of national film to describe a Hong Kong product is, if not incorrect, at least very complicated. Hong Kong film (until the hand-over to the People’s Republic in 1997) was produced in a colonial context, by a diasporic community of Chinese, from different regions in China. Hong Kong itself is located outside of the territorial boundaries of China proper. The notion of local cinema does not capture fully the notion of Hong Kong cinema either. After all, so much of Hong Kong cinema is geared towards a diasporic audience and produced with funding from sources outside of Hong Kong. Moreover, in terms of content, films such as Jing Wu Men do not address local Hong Kong concerns either, at least not directly. Indeed, even in terms of production, much of Hong Kong cinema is created by a community that does not associate itself all that strongly with Hong Kong or the local language spoken in Hong Kong, Cantonese.

Hong Kong cinema, then, is perhaps best understood as diasporic Chinese, produced by and geared towards an audience that imagines itself as belonging to a motherland and national culture of China that is always slightly out of reach. To understand the sense of longing for the motherland of China typical in such films, it is good to read the article by Tan See KAM (see “Student Readings.”)

Transnational Film and the Appeal of Bruce Lee Across National Borders

In terms of international reception, the film Jing Wu Men was a huge hit with audiences abroad who ethnically and nationally were very far removed from a Hong Kong, mainland, or overseas diasporic Chinese audience. In the United States and Europe, but also in places such as India and Africa, martial arts films, especially the films of Bruce LEE, were hugely popular.

One rather unexpected place where Bruce LEE became a hero was in Harlem. There are different ways of understanding this appeal of Bruce Lee by African Americans. In terms of film distribution, the article by David DESSER (see “Student Readings”) is quite helpful in showing how studios realized the appeal of Lee’s films with an African American audience and thus self-consciously started targeting these audiences with Hong Kong martial arts flicks.

Usual tactics included double-billing of blaxploitation with Hong Kong films. Another important source can be found in Vijay PRASHAD’s article (see “Student Readings”), which shows that the local, African-American reception in the United States of Hong Kong martial arts films was closely linked to different forms of militant activism characteristic of the late sixties and late seventies.

The nature of this transnational audience is difficult to grasp. However, we can find evidence of the African American fascination with Hong Kong martial arts film in a variety of ways. Many of the blaxploitation films produced during the early seventies, for instance, show clear influence from Hong Kong martial arts flicks, often including protagonists skilled in one lethal martial art or another. The Shaolin Dolemite series for instance, features an army of deadly Shaolin kung-fu prostitutes. Most famously, Jim KELLY, a black-belt karate champion starred in a series of blaxploitation films centering on the hero “Black Belt Jones.” Jim Kelly of course also starred in the last movie Bruce LEE made while still alive, Enter the Dragon, a film co-produced by the Hong Kong studio Golden Harvest and the American Warner Brothers.

Influence of 1970s kung-fu films on the African American audience can also be traced to the Blade movies of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century and films that co-star Chinese and African-American protagonists such as Romeo Must Die (which starred Jet LI with Aaliyah as his love interest) or even Rush Hour (which starred Jackie CHAN next to Chris TUCKER). Perhaps the most interesting influence of seventies Hong Kong martial arts movies on the African American imagination is found in the music of the Wutang Clan, a rap consortium whose albums include samples from 70s Hong Kong martial arts movies such as Eight Trigram Pole Fighter, 36th Chamber of Shaolin, Return to the 36th Chamber of Shaolin, and Disciples of the 36th Chamber of Shaolin. Most recently a Korean martial arts fantasy tale, entitled Whasanga (2001), was dubbed by a host of stars from the American rap scene, including André 3000, Method Man, Big Boi, and Snoop Dogg. The American remake, entitled Volcano High, might not be considered high-class cinema, but it does speak to the continued African-American fascination with Asian kung-fu cinema and various ways in which Asian martial arts cinema is appropriated across national boundaries.

The Body and Writing in Jing Wu Men

Jing Wu Men is an action film. As such, the attraction of watching this film lies not in terms of plot, psychological realism, but rather simply in the sensation of seeing Bruce LEE take his shirt off, displaying his muscular body, and defeating a seemingly endless series of opponents. Simply put, Bruce Lee offers the audience a physical spectacle and visual pleasure that is difficult to describe in terms more sophisticated than “cool” or “wow.” By looking at the relationship between body and writing, however, it is possible to get students to think about the spectacle of physical action in more depth.

In terms purely of physical display, Bruce LEE’s body performs at least three clear functions. First, as Stephen TEO shows, Bruce Lee’s body in Jing Wu Men is directly tied to Chinese national pride. Bruce Lee uses his physical skills and Chinese martial arts to defeat imperialist opponents on a most basic, bodily level. Second, as Yvonne TASKER argues, by constantly taking off his clothes and showing his hard muscular body, Bruce Lee creates a Chinese masculine hero that an audience can identify with.6 Like any hero on the white screen, Bruce Lee creates a presence that an audience can desire and emulate. The main difference is that Bruce Lee is one of those rare heroes on the white screen who clearly is not white, yet still appeals to white audiences. Moreover, as Tasker argues, is it not women, rather than men who are supposed to take off their clothes on screen? Third, as Prashad has argued, by taking off his clothes, Bruce Lee highlights the fact that he fights unarmed. If James BOND represents the ultimate imperialist force of high-tech sophistication, Bruce Lee’s bare hands and feet represent a powerful ideal of struggle against injustice by those who have nothing but their hands and feet.

In Jing Wu Men, Bruce LEE’s pure physicality seems highlighted even more because his displays of physical action are constantly being set up against the power of writing. Next to the display of the half-naked body of Bruce Lee, the principle other object as lovingly portrayed by the camera consists of a variety of written signs.

The sign “Sick Man of Asia”

Amidst the memorial service in the main hall, in the middle of a speech commemorating the spirit of the martial arts teacher, two Japanese martial artists and a Chinese interpreter arrive with a big sign, “Sick Man of Asia.” Whereas the various banners in the memorial hall represent respect, this particular sign is a calculated inversion of the usual commemorative banner: while similar in form, it represents a huge insult.

It is crucial to understand the written form of this particular insult. Writing, like any form of linguistic expression, can be understood in a variety of ways: lyrical (an expression of self), realistic (description of reality), etc. In this particular case, the phrase “Sick Man of Asia” represents a challenge, an insult, but most importantly it represents a label, a form of writing that seeks to bestow identity. If this particular phrase, “Sick Man of Asia”, can be left in tact, if the gathered Chinese martial artists refuse to answer the challenge, then this label will effectively describe the nature of the Chinese nation and its people. Of course, it does not take long before Bruce LEE accepts the challenge, visits the Japanese martial arts school, beats the gathered Japanese martial artists, rips the sign “Sick Man of Asia” into pieces, and forces the two Japanese martial artists to eat their words, literally, by stuffing the sign into their mouths.

As this example shows, a written sign such as this can represent a challenge to the identity of the Chinese people by representing the Chinese nation as a physical, albeit diseased body. Bruce LEE obviously comes to represent the super-healthy Chinese body. By physically beating up China’s opponents and then physically destroying the written sign, he proves that the label is inaccurate.

One final note should be made. This sign, “Sick Man of Asia” also represents the beginning of plot amidst all of the action. The label “Sick Man of Asia” is not only an insult to the Chinese people; it is directly tied in terms of plot to the death of Bruce LEE’s master JIA Huoyuan. The Japanese assert that Jia Huoyuan died of pneumonia and the label “Sick Man of Asia” serves as a reminder of the weakened state of China as a nation, by claiming that the man indeed died of a disease. As a challenge, the sign presents the beginning of many action sequences where Bruce Lee will physically prove that Chinese men are not weak. Linked to the death of Jia Huoyuan, however, the sign is also a clue in a plot where the eventual goal is to uncover the original cause of death. As Bruce Lee discovers, Jia Huoyuan was poisoned by the Japanese and did not die of pneumonia.

The Sign “No Chinese and Dogs Allowed”

In a seemingly random segment (the moment has clearly been inserted into the film for its strong symbolic significance, but has absolutely nothing to do with the plot of the film), we see Bruce LEE come to a park in Shanghai where he destroys the sign “No Dogs or Chinese Allowed.” Whereas the sign “Sick Man of Asia” represented a label that sought to bestow an inferior identity on the Chinese people, this particular sign represents a prohibition or law.7

As a legal prohibition, the sign is reminiscent of the various unequal treaties that bound the Chinese nation by international law into a variety of painful concessions. The various unequal treaties are too numerous to enumerate here, but one particular element of the unequal treaties needs to be highlighted — the extra-territorial rights awarded to foreigners. Under the unequal treaties, foreigners were no longer tried under the Chinese legal system. While various foreign nations imposed this rule because they saw Chinese law as inhuman and unjust, for the Chinese it meant that foreigners who broke the law on Chinese soil (any of the treaty ports) were not likely to be actually persecuted and punished.

The film, which tells of a Chinese martial arts master poisoned by the Japanese, serves as an excellent example of such an injustice written into international treaties. Throughout the movie we see courtrooms as well as various representatives of the law, yet none can provide justice. The point of the film is simple: in pre-WWII Shanghai, a colonial treaty-port, the Chinese could not expect any justice from a system that had inequality written into its very legal statutes. By breaking the written sign hanging above the park in a spectacular flying kick, Bruce LEE once again proves that his physical body is stronger than any written prohibition forced upon the Chinese. The film itself, of course, is an extension of this single dramatic moment. Through a series of battles, Bruce Lee physically provides justice in a corrupted legal system.

The Jing Wu Men School

In the opening shots of the movie, just after a brief voice-over explaining the history of the Jing Wu Men martial arts school, we see a rickshaw pull up in front of the front-gate of the martial arts school. Above the gate, we see three characters, Jing Wu Men 精武門. How are we to interpret this particular sign and how does this particular sign allow us to understand how different audiences will respond differently to this film?

First, it should be understood that Jing Wu Men is the Chinese title of the film. For a western audience, unfamiliar with the longer history of the Jing Wu Men martial arts school and unable to read Chinese characters, such a title would of course be quite meaningless. Indeed, a western audience (including most students) is likely to miss the sign of the school during these opening scenes. For a Chinese audience, however, this sign immediately establishes a variety of crucial meanings.

On a most basic level, the sign above the gate establishes a physical location. In cinematic terms, the shot of the “Jing Wu Men” school is an establishing shot, a shot that tells the audience where we are in geographical terms.8 Indeed, throughout the film we see such establishing shots where the first image the audience sees is a sign in calligraphy that establish the particular place.

More importantly, however, “Jing Wu Men” is the place where through physical training students can master martial arts, arm their body against imperialist aggression, and disprove that China need not be the Sick Man of Asia. In terms of space, Jing Wu Men is merely a martial arts school, but as a concept Jing Wu Men represents a physical regimen of physical discipline, a recipe and a promise for a strong, independent Chinese nation.

The sense of empowerment that is felt from recognizing these three characters (“Jing,” “Wu,” and “Men”) is most beautifully illustrated in the opening credits. When the credits begin to roll, there is of course the title of the film, which in the international version will read either “Chinese Connection” or “Fist of Fury,” but which in Chinese would of course spell “Jing Wu Men.” We should moreover note that during the credits these three characters “Jing” meaning “excellent,” “Wu” meaning “martial,” and “Men” meaning “School” are constantly flashing in animated fashion in front of the eyes of the audience. Meanwhile, the film shows us the picture of muscular Bruce LEE frozen in a striking pose. Simply put, from the beginning of the film, Jing Wu Men employs the sign “Jing Wu Men,” combined with the body of Bruce Lee, to promise an imaginary space an audience can enter. In this space, the audience can identify with the muscular hero Bruce Lee who destroys one set of unjust writings to physically “write” a new spirit of a strong Chinese nation, “Jing Wu Men.”

It is interesting to note that in real life, Bruce LEE represented a form of martial arts philosophy that sought to abandon any kind of particular form. Bruce Lee’s much celebrated martial arts style, “Jeet Kun Doo” (Way of the Intercepting Fist), did not associate itself with any particular style of martial arts, nor with any particular national form of martial arts. In the film, however, it is clear that Jing Wu Men represents a Chinese style of martial arts. Moreover, within the world of Chinese martial arts, Jing Wu Men represents a particular style, with its own movements, its own lineage of masters, etc. As such, the practice of martial arts within a system such as the Jing Wu Men school represents a heavily prescribed set of physical movement that itself can be seen as a disciplining of the body.