|

Buddhist Art in East Asia: Three Introductory Lessons towards Visual Literacy

De-nin D. Lee Department of Art Bowdoin College |

|

A picture paints a thousand words, and for students of things foreign, a picture can make an immediate and lasting impression. Images of Buddhist art can be powerful pedagogical additions to courses that teach about Buddhism or Asian culture. Buddhist art comprises a tremendous range of objects, images, and sites including jewel encrusted reliquaries fashioned from precious metals, simple yet mesmerizing monochromatic ink landscape paintings, and temple complexes housing shrines and votive sculptures for the pilgrim to worship. The vast quantity of Buddhist art can easily overwhelm, and by necessity this unit selects a limited number of works of art to introduce students to the subject of Buddhism.

The most immediate goal of this unit is to familiarize students with a few examples from the vast array of East Asian Buddhist art. A more general goal is to achieve visual literacy, which means being able to analyze and articulate how art conveys meaning to and solicits reactions from its audience. (For more about visual literacy, see Amy Tucker, Visual Literacy: Writing about Art, Boston : McGraw Hill, 2002.)

This unit uses well-known examples of Buddhist art from East Asia , but it does not attempt to organize the material into chronological, geographical, or stylistic order. Rather, the unit features three methods of approaching Buddhist art:

1. iconography , which aims to identify figures and subjects,

2.

formal, or stylistic analysis , which sees the formal qualities of a work of art as meaningful, and

3.

contextual analysis , which locates and understands a work of art within its original historical, political, economic, religious, or other social context.

These methods are not unique to Buddhist art; hence, once the student has grasped the basic tools, he or she may be better able to analyze and understand images from not only other religions but also in the course of daily life.

The unit is aimed primarily at the non-specialist and intended for courses other than art history. Likely courses include:

- Introduction to East Asian Culture

- Introduction to East Asian Religion

- Asian and Comparative Religions

- Introduction to Buddhism

Instructors may choose to teach the three lessons as the primary material for one or two class meetings. Alternatively, it is possible to teach the les lessons separate or incorporate one or more specific images into class meetings that focus on other topics.

The examples have been selected for their variety and instructive value. In some instances, an example that the instructor may present to students is followed by exercises for students to discuss. In other instances, the instructor must present the example(s) or lead students in a discussion of the exercise(s).

The best way to view art is to see it in person, but since this is not always possible, the internet offers an alternative. At a minimum, thousands of Buddhist images may be found on the web. Here is a tip for searching for images on-line: enter the terms of your search into the Google search engine, then select “images.”

Iconography is the method of art history that uses texts in order to identify the subjects of artworks. Iconography, as developed in the study of European art, first used the myths from ancient Greece and the books of the Old Testament and the Gospels to identify the figures and subjects of Greek and Christian art. For Buddhist art, iconographers rely on Buddhist writings, primarily sutras and their commentaries, to identify figures such as the Buddha or bodhisattvas as well as narratives. (For a classic essay on iconography, see Erwin Panofsky, “Iconography and Iconology” in Meaning in the Visual Arts: Papers in and on Art History, Garden City: Doubleday, 1955.)

A. The Buddha: Introduction

According to legend, the Buddha bore the thirty-two marks of a great man, including wheels on the soles of his feet, an urna (resembling a dot between his eyebrows or at center of the forehead), and an ushnisha, a fleshy protuberance atop his head (McArthur*, p. 95). In addition to these superhuman physical marks, the Buddha has elongated ears. Typically, he wears a monk’s robe and shuns jewelry. Frequently, one finds a halo framing his head and a mandorla, or body halo, surrounding his body. He may be shown seated on a lotus throne or standing on a lotus pedestal. The Buddha’s mudra, or hand gesture, communicates meaning. For example, a raised right hand with palm facing outward — the abhaya mudra — tells the viewer to “fear not.” Other hand gestures communicate “gift-giving,” “turning the wheel of the law” or “preaching,” “calling the earth to witness (his enlightenment),” and “meditation” (McArthur, pp. 111-117).

*Meher McArthur, Reading Buddhist Art: An Illustrated Guide to Buddhist Signs &Symbols, London : Thames & Hudson, 2002.

In Mahayana Buddhism (see also http://www.exeas.org/resources/foundations-text-4.html), we encounter numerous other Buddhas, such as Amitabha and Maitreya. All Buddhas may share common features as described above, but they may also have distinctive iconographic features. Amitabha is frequently pictured presiding over or with reference to his Western Paradise; Maitreya may be shown seated with left leg pendant, right elbow resting on right knee, right hand raised to cheek, eyes lowered, and wearing a crown. Because Maitreya is the Buddha of the Future, he is thought of and portrayed as a bodhisattva in the present (see, for example, Image 3 under “The Buddha: Exercises for Students” below).

A. The Buddha: Example for the Instructor

The instructor may project this image on a screen, using a pointer to identify the iconographical features that identify the Buddha and the Western Paradise.

Image:

|

Jocho, Amida (Sanskrit: Amitabha) Buddha, 1053 CE (Byôdô-in, Uji, Japan). Included here by permission of Thames & Hudson In Robert E. Fisher, Buddhist Art and Architecture, rev. ed., London: Thames & Hudson, 2002. pl. 140 This Buddha may be identified by his monk’s robe, ushnisha, urna, elongated earlobes, halo, and flaming mandorla. He sits on a lotus throne and is framed by an elaborate canopy above him. His hands rest upon his lap in a mudra of meditation. Small celestial dancers and musicians on the walls surrounding him allude to the pleasures of the Western Paradise, thus we may identify this Buddha as Amida, or Amitabha (see also Lesson Three “Contextual Analysis” below). |

A. The Buddha: Exercises for Students

The instructor may project these images on a screen, asking students what is being depicted and the features that allow them to make that identification. Instructors may also ask students to compare images of the same subject, asking what visual changes can be made while still ensuring the proper identification of the subject.

Images:

1. “Avery Brundage” Seated Buddha, 338 CE ( Asian Art Museum of San Francisco , B60B1034)

http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/exhibit/religion/buddhism/i_and_i/b60b1034.html

(Also in Robert E. Fisher, Buddhist Art and Architecture, rev. ed., London : Thames & Hudson, 2002, pl. 78.)

2. Altarpiece with Amitabha and Attendants, 593 CE ( Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 22.407)

Available from the MFA website by entering the catalog number “22.407” in the “Collection Search” box: http://www.mfa.org/collections/index.asp

3. Seated Maitreya, late 6th c. (National Museum of Korea, National Treasure no. 78)

Or

Contemplative bodhisattva, early 7th c. (National Museum of Korea)

See Robert E. Fisher, Buddhist Art and Architecture, rev. ed., London : Thames & Hudson, 2002, pl. 113.

4. Amitabha’s Western Paradise, north and south murals, Cave 172, mid-8th c. (Dunhuang, Gansu Province, PRC)

See Richard M. Barnhart et al, Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting, New Haven : Yale University, 1997, pls 66a and 66b

B. Bodhisattvas: Introduction

Bodhisattvas are enlightened beings who choose to delay entry into nirvana and remain in the cycle of birth-death-and-rebirth, or samsara, in order to aid all sentient beings in their quest for enlightenment. Bodhisattvas may be distinguished from the Buddha by the presence of a crown and elaborate jewelry. They may share some features with the Buddha such as elongated earlobes, an urna, a halo, etc. Bodhisattvas may be found flanking the Buddha in iconic compositions as in multi-figured altarpieces or in isolation. The most popular bodhisattva in East Asia is Avalokitesvara (Chinese: Guanyin, Korean: Kwanum, Japanese: Kannon). Avalokitesvara has many forms, sometimes appearing with eleven heads or a thousand arms and eyes, sometimes holding a lotus or water container, sometimes with an image of Amitabha in his crown, and sometimes as distinctly feminine.

B. Bodhisattvas: Example for the Instructor

The instructor may project this image on a screen, using a pointer to identify the iconographical features that identify the bodhisattva. He or she may also choose to compare the bodhisattva with the Buddha.

Image:

|

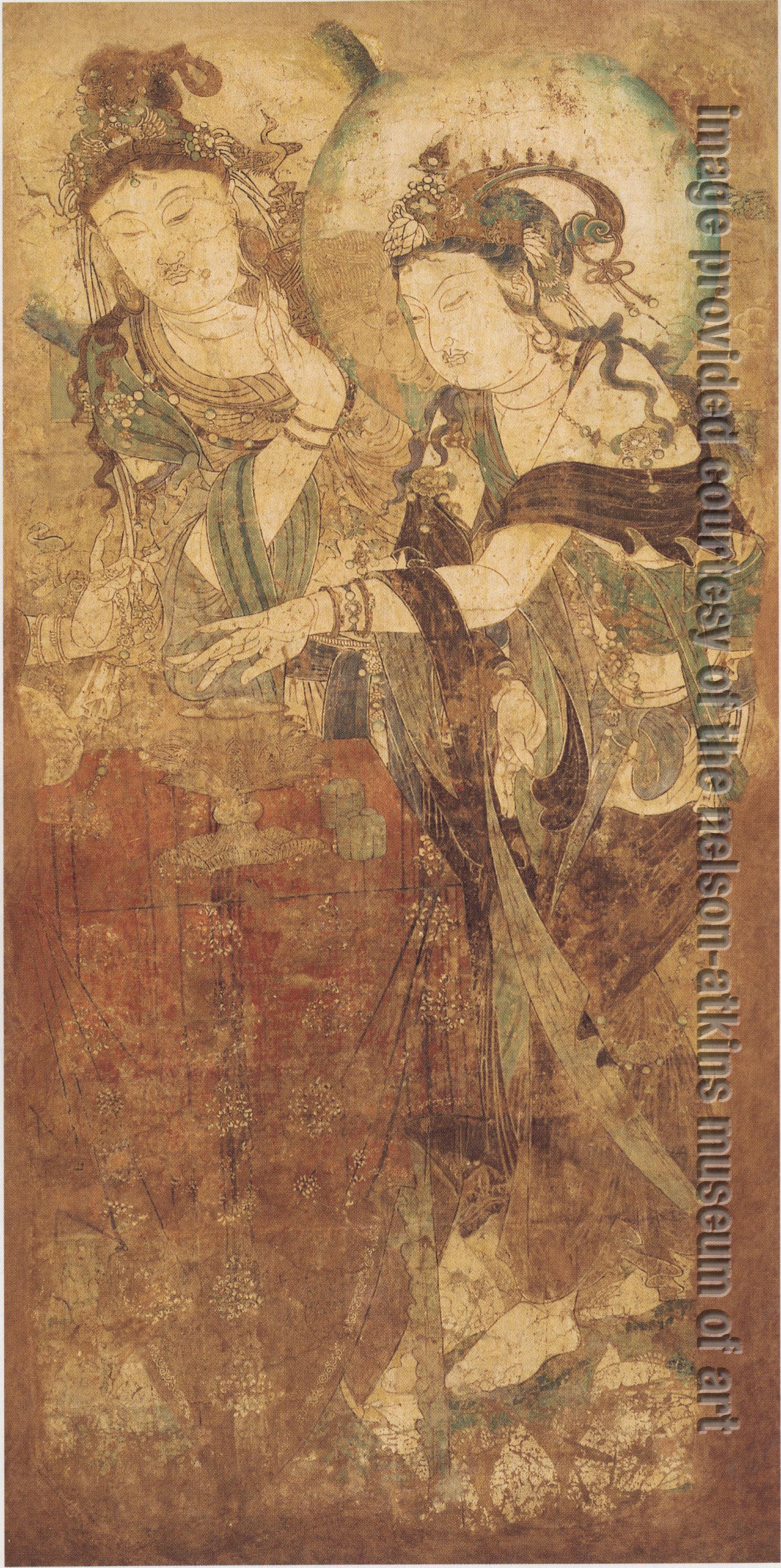

Two Puja Bodhisattvas Burning Incense, Chinese, ca. 951-953. Ink and color on clay, 69 x 35 1/2 x 1 1/2 inches (175.26 x 90.17 x 3.81 cm). The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Gift of Mr. C. T. Loo, 50-64 A. Included here by permission of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Also in Richard M. Barnhart et al, Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting, New Haven : Yale University, 1997, pl. 82. With their intricate headdresses, elaborate jewelry, elongated earlobes, and haloes, these two figures may be identified as bodhisattvas. Their feet appear to be supported by lotuses and scarves swirl about their arms as they prepare incense on an altar table. |

B. Bodhisattvas: Exercises for Students

The instructor may project these images on a screen, asking students what is being depicted and the features that allow them to make that identification. Instructors may also ask students to compare images of the same subject, asking what visual changes can be made while still ensuring the proper identification of the subject.

Images:

1. Kudara Kannon, mid 7th c. (Horyu-ji, Nara , Japan )

See Sherman E. Lee, A History of Far Eastern Art, 5th ed., New York : Harry N. Abrams, 1994, fig. 218.

2. Eleven-headed Guanyin, ca. 1101-27 c. (Cleveland Museum of Art, 1981.53)

http://www.clevelandart.org/Explore/work.asp?searchText=guanyin&x=2&y=11&recNo=0

&tab=2&display=

Or

C. Narratives: Introduction

Buddhist narratives include events from the Buddha’s biography, such as his birth and the preaching of his first sermon. Jataka tales tell the stories of the Buddha’s past lives as noble animals and persons who perform exceptional sacrifices. Other narratives involve famous Buddhist figures, particularly monks.

C. Narratives: Examples for the Instructor

The instructor may project these images on a screen, using a pointer to identify the main figures and events of these narratives.

Images:

1. Prince Mahasattva’s sacrifice, from the Tamamushi shrine, 7th c. (Horyu-ji, Nara , Japan )

See Sherman E. Lee, A History of Far Eastern Art, 5th ed., New York : Harry N. Abrams, 1994, fig. 215

While out riding, a prince and his brothers come upon a starving tigress and her cubs. The brothers return home to bring food, but the prince remains behind. Fearing his brothers will not return in time, he decides to sacrifice his own body to feed the animals. The tigress and her cubs are weakened from starvation, so the prince must jump off a cliff, breaking his body into smaller pieces. When the brothers return, they find only the prince’s bones. They collect bones and build a pagoda for the relics.

In this single panel, the Buddha is represented three times representing three moments in the narrative: the Buddha undressing, the Buddha falling through the air, and finally the tigress and cubs consuming his broken body. This type of representation, multiple episodes in a single scene, is known as continuous narration.

2. Liang Kai, Huineng, the Sixth Chan Patriarch, Chopping Bamboo at the Moment of Enlightenment, ca. 1150-1175 ( Tokyo National Museum )

Also in Sherman E. Lee, A History of Far Eastern Art, 5th ed., New York : Harry N. Abrams, 1994, fig. 487.

A native of Xinzhou in south China , Huineng was the sixth Chan (Japanese: Zen) patriarch in a lineage that stretched back to Bodhidharma, the purported first patriarch, or founder of Chan Buddhism. According to Chan history, Huineng was selling firewood when he heard the dharma, marking his moment of enlightenment. He then sought out a teacher, Hongren, who later made Huineng his successor. This painting uses only black ink to depict Huineng about to cut bamboo at the moment he hears the dharma. The asymmetrical composition — a towering tree trunk rises to the left of a crouching Huineng — focuses our attention on Huineng’s figure, suggesting imminent action and enlightenment (see Lesson Two “Formal Analysis” below).

C. Narratives: Exercise for students

Image:

Prince Mahasattva’s sacrifice, Cave 72, Dunhuang

See Roderick Whitfield, Susan Whitfield, and Neville Agnew, Cave Temples of Mogao: Art and History on the Silk Road , Los Angeles : The Getty Conservation Institute and the J. Paul Getty Museum, 2000, p. 83.

The same story as in Narratives: Examples for the Instructor, Image 1 above is depicted. The instructor may pose the following questions to the class as a whole or distribute the questions as a worksheet to small groups.

- Where does the story begin? Where does the story continue? Where does it end?

- Which moments in the story are represented?

- Compare this artistic interpretation to that on Prince Mahasattva’s sacrifice, from the Tamamushi shrine. How do they differ?

- Think about different film versions of the same story, or different actors playing the same role. Which version of Prince Mahasattva’s sacrifice do you prefer? Why? Is one version more effective than another in communicating the story’s drama and moral? Why?

Formal Analysis: Introduction

Formal analysis asks the question, “how does form generate meaning?”

When analyzing the formal aspects of works of art, it is useful first to pay close attention to the medium, or material. For example, clay is more malleable than stone; gilt bronze is more dazzling than monochrome ink on paper. Sculpture relies on the play of light and shadow across concave and convex surfaces while painting uses colors and lines to create the illusion of three-dimensional figures and motifs.

After determining the medium, we should analyze the work, considering such formal aspects as 1) color, 2) line, 3) shape, 4) light/shadow, 5) space 6) scale and 7) texture. Consider:

- whether and how the artist uses bright colors to capture our attention,

- how agitated or gentle lines suggest energetic activity or peaceful stasis,

- how large or repeated shapes dominate while intricate patterns provide extra visual interest,

- how light areas coincide with key aspects of the work,

- whether the work appears spacious or cramped,

- how the primary figure looms over seemingly miniature subsidiary figures,

- or how smooth textures suggest idealized or perfected bodies.

We should think of visual arts as a language and these are just a few ways in which formal elements can communicate meaning.

Next, consider composition, that is, how the artist has arranged the various elements of the artwork. We might ask whether the composition is symmetrical or asymmetrical, or whether it seems balanced. Symmetry and balance suggest harmony and stability while asymmetry tends to convey movement and activity. Important elements may be located in privileged places such as the center or the top of a composition. Extra space, framing devices, and pedestals or platforms may also be used to establish hierarchy. Be sure to ask how motifs in the artwork interrelate.

Take time to observe your own viewing experience. Ask yourself what captures your attention first, what other elements you then see, what mood or emotion you feel. Can you explain your observations and emotional responses? In other words, which formal aspects of the work of art direct the movements of your eyes and encourage you to feel a certain way?

Formal Analysis: Exercises for students

Instructors may project these images on a screen and lead students through the questions noted above. Alternatively, the questions may be posed as a worksheet to smaller groups for discussion. Yet another possibility is to discuss one image together in class, while assigning the other as a short writing exercise, either in class or as homework.

Images:

1. Liang Kai, Huineng, the Sixth Chan Patriarch, Chopping Bamboo at the Moment of Enlightenment, ca. 1150-1175 ( Tokyo National Museum )

Also in Sherman E. Lee, A History of Far Eastern Art, 5th ed., New York : Harry N. Abrams, 1994, fig. 487.

Notes for the instructor : This painting consists of only ink on paper, and yet Liang Kai has brilliantly captured a sense of mental concentration and of physical tension that nevertheless conveys calmness and control. Liang creates this atmosphere by the manner in which he uses ink and water, how he moves his brush across the paper, how he arranges the composition of the objects in his painting and how he chooses to leave other spaces in the white paper blank. For example, Liang mixes only a small amount of water with his ink, so that his bush strokes look dry and coarse. He sparingly describes the setting: only a few dry, broad brushstrokes suggest an old tree and a stalk of bamboo with few leaves. The ground is no more than a smattering of dry streaks, and in the distance, nothing. The arrangement of objects, or the composition of the painting, leads the viewer’s eyes from one motif to another. Here the tree trunk delivers our eyes to the crouched body of Huineng. Empty spaces also direct our attention, just as the lack of excess elements in this painting forces us to focus on the impending action of the painting’s one figure. The lack of color allows us to appreciate better the variety of tones and textures produced by ink alone, and it imparts a feeling of seriousness to this pregnant moment. Liang Kai’s deft handling of the brush is evident in the subtle modulation (thickening and thinning) and the apparent quickness of the lines that make up Huineng’s body as well as the fine lines of his hair and whiskers. The pose of Huineng’s body — much of it scrunched into a ball, while one arm stretches out to steady the bamboo and the other poised with knife in hand — conveys, like a compressed spring, a sense of imminent energy. The variety of ink tonalities and brushstrokes provide visual satisfaction while the composition of Huineng’s round body between two not-quite-vertical elements effectively captures a moment of perpetual anticipation.

2. Altarpiece with Amitabha and Attendants, 593 ( Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 22.407)

Available from the MFA website by entering the catalog number “22.407” in the “Collection Search” box: http://www.mfa.org/collections/index.asp

Notes for the instructor : If Liang Kai’s Huineng encourages the viewer to feel a sense of suspended activity, then this altarpiece suggests an enduring stillness and splendor. Amitabha sits upon an elaborate lotus throne surrounded by dutiful disciples and bodhisattvas. He is larger than the others and placed at the center of the composition both of which suggest a hierarchy of importance. Framing Amitabha’s face is a flaming halo whose shape is echoed by a jeweled canopy. On a lower altar before him an incense burner rests between a pair of seated lions and guardians. Broken only by the Buddha’s mudras, the composition’s symmetry generates a sense of perfect balance. The long, slender bodies of the figures are like columns and merge almost uninterrupted with the jeweled canopy. Originally, the bronze material would have been highly reflective thereby adding further to the brilliance of Amitabha’s Western Paradise.

Contextual Analysis: Introduction

Contextual analysis asks the questions, “what was the original context of the image or object, and how does the knowledge of that original context contribute to our understanding of the image or object?” Related questions include, “what was its function?” and “what does the form tell us about the function?” Comprehensive responses to these types of questions typically require significant research, but for introductory purposes, it may be important simply to ask and consider the questions. It is also important to keep in mind that before many Buddhist objects and images entered private or museum collections and became the subject of art history, they were venerated and used for liturgical and other religious purposes. Buddhist works of art were frequently commissioned in order to gain merit, but patrons may also have had political and social motivations as well. The example that follows offers only brief remarks and is intended to be suggestive, not conclusive.

Contextual Analysis: Example for the Instructor

Jocho (d. 1057), Amida (Sanskrit: Amitabha) Buddha, 1053 (Hôôdô, Byôdô-in, Uji , Japan )

In Robert E. Fisher, Buddhist Art and Architecture, rev. ed., London : Thames & Hudson, 2002, pl. 140.

In this example, we see how iconographic and stylistic features carried over into the context in which Buddhist art was displayed. Jocho’s Amida Buddha occupies the central space of the Phoenix Hall, a pavilion built by Yorimichi (990-1074), a member of the Fujiwara family, during the so-called Latter Days of the Law (Japanese: mappô). According to Buddhist chronology, this a period was so far removed from the Buddha’s time on earth that people felt that achieving enlightenment would be impossible. Rebirth into Amida’s Western Paradise would be about the best one could hope for. Thus, Buddhist patrons commissioned works of art that mimicked the Western Paradise in an attempt to make palpable the possibility their own rebirth into it. The sculpture and its environment is an expression of Yorimichi’s belief specifically and of his generation generally in mappô and the hope represented by the Western Paradise , or Pure Land . The plan of the Phoenix Hall, which includes the sculpture, a building and a pond, was a conscious re-creation or representation of the Western Paradise . The architectural layout of the hall, with its two outstretched wings and a rear hall, suggests a bird in flight. That bird faces a pond over which Amida presides. With his hands placed together in a possible variant of the meditation mudra, the statue of the Amida appears to have a kind of world-weary yet serene and impassive expression, as if in acknowledgement of Buddhist theology’s own long journey into the era of mappô. At one time, paintings depicting the raigô, the descent of Amida, adorned the inner doors of the building, serving as attendants who would welcome a devotee to the Western Paradise.

Richard M. Barnhart et al, Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting, New Haven : Yale University , 1997.

Robert E. Fisher, Buddhist Art and Architecture, rev. ed., London : Thames & Hudson, 2002.

Sherman E. Lee, A History of Far Eastern Art, 5th ed., New York : Harry N. Abrams, 1994.

Penelope Mason, History of Japanese Art, rev. ed., New York : Prentice Hall, 2004.

Meher McArthur, Reading Buddhist Art: An Illustrated Guide to Buddhist Signs & Symbols, London : Thames & Hudson, 2002.

*Useful for looking up basic information about Buddhist figures, symbols, and several major Buddhist sites in Asia .

Erwin Panofsky, “Iconography and Iconology” in Meaning in the Visual Arts: Papers in and on Art History, Garden City: Doubleday, 1955.

Amy Tucker, Visual Literacy: Writing about Art, Boston : McGraw Hill, 2002.

Roderick Whitfield, Susan Whitfield, and Neville Agnew, Cave Temples of Mogao: Art and History on the Silk Road , Los Angeles : The Getty Conservation Institute and the J. Paul Getty Museum, 2000.

Dialogue and Transformation: Buddhism in Asian Philosophy (teaching unit)

http://www.exeas.org/resources/buddhism-asian-philosophy.html

Foundations and Transformations of Buddhism (background reading)

http://www.exeas.org/resources/foundations-of-buddhism.html

Smithsonian Free Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

http://www.asia.si.edu/education/

Select “The Art of Buddhism” to download 3 PDF files for teaching about Buddhist Art.

The Silk Road : Buddhist Art by Mrs. Ledig-Sheehan, Marymount School

http://www.marymount.k12.ny.us/marynet/TeacherResources/SILK%20ROAD/html/budart.htm

An overview of Buddhist art on the Silk Roads.