| The present physical interpretation of power is but a manifestation of the larger process of turning everything into an object, generally an object of manipulation. |

| -Henryk Skolimowski, "Power: Myth and Reality" |

In this chapter, I analyze my key theoretical concepts - power and knowledge - and explore some of the complex sets of relationships between them. Rather than providing parsimonious but oversimplified definitions, I draw eclectically on existing conceptualizations. This approach is particularly suitable for a discussion of "essentially contested concepts" (Gallie 1956), a label that applies well to power and knowledge.

My interest is in the intersection of knowledge and power in international environmental politics. Hence, I highlight notions of power that include legitimacy, consensus, and access to information, sketching the limitations of the structural and materially based conceptions dominant in recent international relations theory. Likewise, I focus on the social and pragmatic aspects of knowledge and its political application. I do not deny the usefulness of other definitions; I merely claim that power and knowledge must be conceptualized in terms broad enough to include a more subtle and interactive understanding of both. Otherwise, one risks falling prey to the modernist fallacy that power and knowledge can be neatly sequestered from one another. In the realm of policy studies, this fallacy becomes part of the "rationality project," with its mission of "rescuing public policy from the irrationalities and indignities of politics" (Stone 1988:4). The modernist fallacy wrongly assumes that scientific and technical knowledge can provide an objective body of facts from which policy can be rationally generated.

I begin with conventional notions of power and work toward a more comprehensive conception that can accommodate the complexity of power that is knowledge based. The prevailing conception of power in the study of world politics is truncated, largely confining power to its physical and manipulative aspects. In contrast, knowledge-based power is productive and discursive, not merely repressive and materialistic. Such an approach makes an important contribution to the study of science in policy decisions, especially for environmental issues. A discursive approach to science in policy emphasizes the rhetorical nature of scientific evidence, argumentation, and persuasion. Information does not emerge in a void but is incorporated into preexisting stories to render it meaningful. Information is framed and interpreted in ways that bolster certain policy positions.

The dominant perspectives on the role of technical expertise in international politics, namely variants of functionalism and the epistemic communities literature, lack the richness and depth of a discursive approach. First, they tend to overstate the ability of scientific knowledge to generate political consensus. Second, because these approaches are agent-centered, they downplay the content and context of discursive practices, thereby obscuring the primary sources of persuasive competence. If, as I argue, discourses are important power centers, then an approach that delves into their inner workings is absolutely essential to understanding science in politics.

Aspects of Power

Power is probably the most elemental concept in the study of politics, yet there is no consensus on what it is, much less how to measure it. If we want to say, for instance, that experts exercise power, we need a notion of power that includes access to knowledge, the value of consensus, and persuasive competence. Power here has positive, capacity-giving dimensions beyond the negative dimensions of domination and control. Experts may disavow their political role, so we need a definition that includes the covert and unintentional exercise of power. Moreover, knowledge-based power is not solely a property of social agents; ideas and discourses themselves may be powerful entities.

Beginning with the most rudimentary notions of power, we may build a conception broad enough to encompass knowledge-based power, and in so doing we may discern its distinctive traits. Power may be defined generically, from the Latin potere, as "the ability to produce an effect," a definition that includes everything from the power of a steam engine to a nation's ability to fight and win a war. Yet the effects of power, like those of gravity, are tangible in a way that power itself is not.

In general, the emphasis has been on the ability of actors to exert intentional control over the actions of others through material threats and incentives, an emphasis consistent with the premises of methodological individualism and behavioralism. Robert Dahl's definition is widely accepted among American political scientists, and certainly influential among international relations scholars: A has power over B to the extent that he can get B to do something that B otherwise would not have done (1957:203).

The issue of unintentional consequences of action, however, is fundamental to structural notions of power. Marxists, for instance, claim that a society's class structure shapes all behavior and thought, regardless of individuals' intentions. In his structural theory of international relations, Kenneth Waltz (1979) rejects Dahl's definition on the grounds that assessing power in terms of compliance overlooks unintended effects and, hence, much of what political processes are about. Whatever its flaws, structural realism is based on the valid observation that conventional behavioral and individualistic notions of power omit consideration of how acts and relations are shaped by social structures.

Structural theories in general make a small contribution to an understanding of knowledge-based power. The ability of experts to affect policy decisions derives from their location within institutionalized structures of knowledge production. 1 They may consciously impact policy - recent history is replete with such cases, from Albert Einstein's famous letter to President Roosevelt to Edward Teller's vocal support for space-based defense - or they may exercise power unintentionally by identifying problems with policy implications or by conveying information at critical junctures in the policy process. In the context of the ozone negotiations, many of the atmospheric scientists involved believed themselves to be totally apolitical. Yet, though guided by the canons of scientific reasoning rather than political convenience, they did exercise power.

While neorealists' structural notion of power moves beyond an agent-centered worldview, in another respect it is entirely conventional. Waltz's view of power is ultimately not very different from that of other realists, with the addendum that it may be exercised unintentionally. Among realists, power is typically taken to entail domination and control by states, it is measured in relative rather than absolute terms (Grieco 1988), and it is usually materially based (Knorr 1975). Such a notion is of limited utility in constructing a conception of knowledge-based power. First, if one changes one's behavior on the basis of new information, it is not clear that one has been dominated or controlled. Second, while some experts may be more influential than others, whether because of their superior professional reputations or their close relations with policymakers, the relative power of states tells us little about the application of knowledge to policy choices. Third, while some states and individuals may have access to more and better information, the intangible nature of ideas means that knowledge-based power is not easily quantified and does not fit easily into a distribution-of-capabilities framework. A major consideration in exploring knowledge-based power is to assess not so much to what degree actors are affected but in what way. As I shall argue later, fundamental nonmaterial factors such as identities and interests are themselves implicated in knowledge-based power. 2

To contrast further knowledge-based power with realist conceptions of power, consider how the two treat questions of domination and interest. Hans Morgenthau, perhaps the most articulate proponent of realist thinking, identifies power with domination and control (Morgenthau and Thompson 1985:11). While this definition no doubt covers many power relationships, it does not so obviously apply to the power of persuasion. Morgenthau states, "realism assumes that its key concept of interest defined as power is an objective category which is universally valid, but it does not endow that concept with a meaning that is fixed once and for all" (Morgenthau and Thompson 1985:10; emphasis added). In the abstract, this definition seems broad enough to cover knowledge-based power, but only if persuasion is considered a subtle psychological method of control. Perhaps a starting point for a revised realist conception of power might be E. H. Carr's notion of power as control over opinion (1964) or Arnold Wolfers's distinction between power and influence (1962). Both of these, however, place knowledge-based power in a decidedly secondary position relative to physical power, particularly military power, so that it remains an underdeveloped concept.

The identification of power as the capacity to realize interests is even more problematic. Morgenthau, for instance, claims that any theory of world politics must be grounded in the concept of "the national interest" (Morgenthau and Thompson 1985:204). Those who argue that states, by definition, pursue their interests run the risk of post hoc reasoning. In this view, interests are surmised by observing the behavior of states. 3 But instrumental action implies goal-oriented behavior, and only a contextual analysis can reveal what goals are being pursued and why. Realists neither explain adequately how interests are formulated nor provide a method for determining when states pursue long-term rather than short-term interests. This dilemma is especially relevant for global environmental problems, where interests in the two time frames are typically pitted against one another. The fundamental insight of reflective approaches is that interests - and even identities - are socially produced and not given in any straightforward way.

In sum, the conventional association of power with domination and control is problematic in situations where an actor is persuaded to revise her conception of her interests through evidence or reasoning. One would want to say that power operates in such a situation, yet one would also want to question the repressive, even malevolent, connotations implicit in most definitions of power. 4 Rather, power should be conceived as potentially generative and rooted in the self-understandings and interactions of people.

One can imagine a spectrum of power relations, ranging from those most rooted in domination and control to those characterized by mutuality and intersubjective understandings. At one end, we would find force, where a powerful actor removes the effective choice to act otherwise. Following force might be coercion, where one actor threatens another; then manipulation, where some level of deceit is involved; then authority, where an actor is recognized as having either a legal or a moral right to impose decisions. Finally, the knowledge-based power of persuasion relies upon evidence and argumentation.

The notion of legitimacy, which is vital to authority and persuasion, crops up frequently in the literature of political theory and domestic politics, but it seems somehow misplaced in the study of world politics. Realists link power with domination and characterize the international system in terms of the principles of anarchy and self-help (Waltz 1979; Grieco 1988; Knorr 1975; Smith 1984). In this view, the normative consensus prerequisite to the possibility of legitimate international institutions does not exist. 5 The Grotian tradition, a minority position until recently, holds that the international system functions according to the norms, beliefs, and rules held in common by national actors (Bull 1977; Rosenau 1973). But theorists rooted in the Grotian tradition typically focus on norms of diplomacy and international law and do not address the issue of scientific knowledge as a source of legitimation. A key question, then, is the extent to which knowledge can serve as an instrument of legitimation and a springboard for consensus in world politics. If confidence in science is a hallmark of the modern era, then scientific knowledge can be expected to facilitate cooperation. But if the production and interpretation of scientific knowledge is an unavoidably political process, then knowledge may feed into new or existing arenas of contestation.

The legitimate exercise of power requires that the relevant actors share certain understandings, whether these be cultural norms, legal structures, perceptions of empirical reality, or deductive logic. While Weber refers to the "legitimations of domination," the very legitimacy of this sort of power relation makes it difficult to accept fully it as domination. Moreover, the mechanisms of legitimation that Weber proposes (tradition, charisma, and rational legality) do not explicitly include scientific knowledge, although any of these mechanisms may apply to science in certain contexts. What is important, though, is that the power of knowledgeable experts, inasmuch as they do not directly determine policy, is rooted in the normative beliefs of policymakers. This observation holds not just for policy issues but for any situation involving expert advice. My doctor, for instance, may be exercising a form of power when he prescribes a medication for me, but this is not domination in the common use of the term. In this sense, scientific and political legitimacy are similar, and neither has much in common with power as overt domination. Related to this, and challenging the coupling of power with agency, is the potential for ideas and beliefs to influence agents and change their senses of self-identity. Social movements may be inspired by the power of an idea, just as individuals may be moved by a powerful conviction.

Another aspect of power that has little in common with overt domination is empowerment, a process by which a group gains an understanding of its best interests and collaborates to achieve them (Fay 1987:130). Social empowerment often involves knowledge-based power, as people are educated to reconceptualize their interests, and even their identities, as they were in the civil rights and women's movements. Scientific knowledge can inspire collective action, as it has in the environmental and consumer movements. In these instances, power entails neither mutually exclusive interests nor physical manifestations but is rooted in intersubjective understandings and "generated" collectively within a social system (Parsons 1967).

Yet it would be a mistake merely to reiterate at the systemic level the traditional teleological concept of power, e.g., the capacity to realize goals. What is lacking in interest-based models, according to Hannah Arendt (1970) and Jurgen Habermas (1977), is a communicative model of action. For Arendt and Habermas, power is more the ability to act in concert through consensual communication than the ability to obtain goals by mobilizing resources. Knowledge production is itself a fundamentally consensual activity, although Arendt and, to a lesser extent, Habermas downplay the pervasive element of struggle in discursive practice.

In the context of international relations, aspect of social life, for that matter, an important question is whether the conditions of communicative rationality proposed by Habermas and Arendt can ever be attained. For science, such communication blocks inhibit the rationality of scientific consensus, and more serious blocks can distort the translation of knowledge into policy decisions. The concept of communicative power might serve as an ideal toward which both science and politics can strive, but it does not shed much light on actual processes.

The notion of power as generative and systemic is also elaborated by Michel Foucault, yet his conception is not nearly so optimistic. 6 For him, power is omnipresent; one is never outside it (1980:141). Foucault rejects the modern belief in the possibility of emancipation from power relations, a belief he attributes to both liberals and Marxists. He speaks of the "productivity" of power, "networks" and "webs" of power, and a "microphysics" of power (1979, 1980, 1983). Spurning the conventional emphasis on the most visible expressions of power, he focuses more on its subtle workings than on its aspects of repression or domination. He asks: "If power were never anything but repressive, if it never did anything but say no, do you really think one would be brought to obey it? What makes power hold good is simply the fact that . . . it traverses and produces things, it induces pleasure, forms knowledge, produces discourse" (1980:119; emphasis added). Yet he does not disregard the reality of domination, noting that it is always exerted in a particular direction, with some people on one side and some on the other (1977:213). Believing that power should be studied at its "extremities," Foucault examines social relations to which the discourse of power traditionally has not been applied, e.g., schools, hospitals, confessionals, etc. To these, I would add the institutions of science and the networks through which science is applied to social problems.

Foucault traces a historical shift from what he terms the "sovereign" form of power as display exercised under monarchy to a more discursive form of "disciplinary" power typical of modernity (1979). He identifies the traditional notion of power as exerted by autonomous agents imposing their sovereign wills as a throwback to premodernity. He is concerned with how "disciplinary power" and other "technologies of power" operate on bodies, how discourse makes the body the object of knowledge and invests it with power. Because individuals are themselves the effects of power, becoming so entwined in networks of power that they are both agents and victims of social control, there is no autonomous subjectivity for Foucault. Knowledge is intrinsic to these networks of power: "between techniques of knowledge and strategies of power, there is no exteriority" (1980:133). 'Truth' is a system of ordered procedures for the production, regulation and circulation of statements.

The Panopticon, Jeremy Bentham's 1791 design for a model prison, epitomizes and concretizes Foucault's notion of disciplinary power. Each inmate is constantly visible from the tower but isolated from other inmates. The effect is "to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power" (Foucault 1979:201). Prisoner becomes jailer; subject becomes object. Thus, the effects of power may be internalized, thereby yielding a form of "contingent subjectivity."

As Foucault recognizes, power need not embody only the negative qualities of the Panopticon; "the productivity of power" entails the construction of knowledge and discourse. These same dynamics of internalization and normalization can be applied to knowledge production and its application to policy decisions. In fact, although Foucault often speaks critically of the workings of power, an agnostic approach is actually more compatible with his general outlook. If power is genuinely productive, then the appropriate attitude should be the suspension of judgment as to its value and significance until one has evaluated the particular situation. If power is truly omnipresent, then, unless one is prepared to adopt a stance of unmitigated pessimism regarding social relations, its effects cannot be universally negative, an observation consistent with Foucault's critique of power as repression. Thus, we may suspend judgment when we examine the power of scientific discourse.

A discursive conception of power may be viewed as part of the larger turning away from materialistic and mechanistic theoretical approaches to social theory. As Henryk Skolimowski observes, power in modern societies has been exteriorized, conceived as an instrument for the domination of nature and other beings (1983). A civilization that views the universe as a mechanical aggregate to be manipulated by technology for the attainment of personal security and comfort, Skolimowski argues, will inevitably reduce power to its physical and coercive aspects. Thus, reflective approaches to world politics, whether consciously or not, may be part of a larger critique of the modern conception of power.

Mark Poster argues convincingly that, as the "mode of information" displaces the "mode of production" in postindustrial society, "knowledge/power" is becoming more relevant than conventional materialist notions of power. He observes:

Knowledge and power are deeply connected and their configuration constitutes an imposing presence. . . . The form of domination characteristic of advanced industrial society is not exploitation, alienation, repression, etc., but a new pattern of social control that is embedded in practice at many points in the social field and constitutes a set of structures whose agency is at once everyone and no one. (1984:78)

Without uncritically embracing the amorphous notion of postindustrial society, a notion to be explored at greater length in chapter 6, one can at least acknowledge the importance of a discursive conception of power.

Poster's allusion to the problem of agency, however, points to what many cite as a basic flaw in Foucault's work: a total rejection of the subject is highly problematic (Habermas 1981; Taylor 1984). If the subject is wholly a product of power, then she has no clear interests, nor has she any basis upon which to confront power. As one critic succinctly puts it, Foucault seems to give us "a hermetically sealed unit; a domination that cannot be escaped" (Philp 1983:40) and, consequently, a deep pessimism about the possibility of human emancipation. While Foucault rejects the discourse of liberation, he frequently speaks of resistance, particularly in his later writings. This, it seems, is our sole deliverance from the hermetically sealed unit. Yet Foucault never offers a rationale for resistance, simply asserting its constant coexistence with power (1980:142).

Contrary to the Enlightenment dream of universal emancipation, Foucault's concept of resistance as ubiquitous yet local rings true, while its abstractness raises doubts about the ontological status of the subject. If people are wholly products of power relations, then who can emerge from the "hermetically sealed unit" to perform acts of resistance? Ultimately, with no theory of action Foucault falls into a deep structuralism. Without subjects or interests, Foucault's support of resistance is so blind and undiscriminating as to seem politically irresponsible (Connolly 1983:332). Beyond the failure to advance normative grounds for action lies the larger failure to produce a theory of social agency. Anthony Giddens puts it bluntly: "Foucault's 'bodies' are not agents" (1984:154).

Foucault's own rhetoric, however, is misleading; in fact, his own model of power demands human subjectivity. The Panopticon, for instance, only functions because of each prisoner's consciousness. Even language, probably the most all-encompassing model of power (Foucault 1973), does not determine all of our thought and actions, though it may circumscribe them. Foucault's achievement, I believe, is to decenter the subject, not to eliminate it. Agents exist, but they should be seen as the effects rather than the fountain of power; power resides neither in agents nor objects but in systems. This is the meaning of "contingent subjectivity," a phrase often invoked by Foucault. Discursive practice involves actors, but they do not function as autonomous agents wielding the power of discourse on behalf of transparent interests. Social processes in general, and even Foucault's own texts, are incomprehensible without some notion of power as the "transformative capacity of human action: the capability of human beings to intervene in a series of events so as to alter their course" (Giddens 1977:348; emphasis in original). Intentionality and domination may be involved, but they need not be. The effects of power may be either positive or negative, depending upon the context of action and the values of the observer.

Stewart Clegg (1989) has proposed a useful typology of theories of power along two axes. One is the dominant trajectory, which extends from Hobbes and encompasses Marx, Weber, and Dahl. Rooted in analogies drawn from classical mechanics, power here is exerted by a sovereign will over the will of others. At its most subtle, sovereign power defines the thoughts of others, as in Marxist conceptions of false consciousness (Lukács 1971) and Lukes's third dimension of power (1974). Clegg's second trajectory, running from Machiavelli to Foucault, sees power as facilitative, strategic, and contingent. Without abandoning the concept of agency altogether, as some poststructuralists seem to do, I find it useful to draw heavily on Clegg's second axis in formulating a discursive conception of power. Knowledge structures the field of power relations through linguistic and interpretive practices, through organizational strategies, and through the contingencies of particular contexts.

Scientific Knowledge and Discourse

"Science" covers too much ground to be defined concisely. It is a product of research, employing characteristic methods; it is a body of knowledge and a means of solving problems; it is a social institution and a source of social legitimacy (Ziman 1984:1.2). In terms of the overall cohesiveness of this book, there are three reasons to address epistemological issues directly. First, without doing so, the authority of scientists appears to be no different from the authority of either priests or dictators. 7 While these forms of authority may overlap at times, an explication of the nature of scientific knowledge can point to some important differences. Second, I hope to outline an image of knowledge that is consistent with and complementary to my analysis of power in the previous section. And third, if scientific knowledge is inherently a discursive product of power relations, even before it is brought into the policy realm, then science in policy making is all the more embedded in power relations. However, my primary interest is in the political dimensions of knowledge, not in complex epistemological questions per se. Consequently, I allude to many arguments in the philosophy of science without spinning them out in their entirety.

Throughout the modern era, the appeal of science has rested on its supposedly increasing access to objective truth, rooted in the basic conviction that there must be some "permanent, ahistorical matrix" to which we can ultimately turn in deciphering the nature of reality (Bernstein 1985:8). The two primary traditions in Western philosophy, rationalism and empiricism, share a basic commitment to objective knowledge, whether through "universal" reason or "unbiased" observation. Probably the most sophisticated attempt to forge a permanent, ahistorical matrix for objective knowledge has been the "physicalist language" of the logical positivists. They claimed to have articulated "absolutely fixed points of contact between knowledge and reality (Schlick 1959:226). But their physicalist language was fraught with confusion and impracticality. Responding to these inadequacies, Karl Popper (1972) defended "objective knowledge" through his doctrine of falsification, which has been abundantly criticized (see Kuhn 1962; Lakatos 1970; Feyerabend 1975). The strongest criticisms derive from the "theory laden-ness of observation," striking at the heart of the entire positivist tradition and opening the door to relativism since objective knowledge requires the possibility of unhindered observation. Despite the many contortions in its quest for a "mirror of nature" (Rorty 1980), the objectivist tradition has failed to establish any permanent, ahistorical matrix, whether in the realm of observation, language or rationality.

The publication of Thomas Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions in 1962 precipitated a storm of controversy by studying science as a fundamentally social activity. 8 For Kuhn, periods of scientific crisis are characterized by intense debate over conflicting paradigms and are resolved through intersubjective consensus. The ultimate acceptance of one paradigm over another is compared to a "gestalt switch" and is achieved through such "unscientific" means as "faith," "aesthetic grounds," and "persuasion" (1962: 121, 158, 159). Although Kuhn has adamantly, and perhaps inconsistently, denied the accusations of relativism (Shapere 1964; Kuhn 1977), he clearly laid the basis for a mountain of work seeking to contextualize science as a social activity.

While Kuhn fails to locate scientific communities within the larger context of history and culture, others have taken up the challenge to show how external social and political considerations affect not just the context of discovery but also the context of justification. For instance, Paul Forman (1979) argues that Weimar Germany's antirationalist culture nurtured the acceptance of an acausal quantum mechanics there. Others have even interpreted the primary inferential mechanisms of science, deduction and induction, as institutions whose authority is fundamentally social (Onuf 1989:101). Feminist philosophers take this perspective even further, arguing that the very categories of objectivity and rationality on which science is based are themselves conditioned by the socializing effects of gender (Keller 1985; Lloyd 1984). Steven Shapin and Simon Schaffer, among others, have wholeheartedly embraced relativism. In Leviathan and the Air Pump, they argue that the debate between Hobbes and Boyle over experimentalism was actually a debate about social order. They reject questions about truth, preferring instead to explore questions of "accepted vs. rejected knowledge" (1985:13–14). Their work may be read as an intellectualized version of "might makes right," conflating knowledge and power.

Scientific communities are infused with power dynamics. Scientists do not independently verify most of what they accept as valid knowledge, nor do they debate it collectively; most of it is accepted on authority, even if that authority is earned by proven competence. Similarly, the scientist gives his allegiance to the "invisible college" of his specialized field, entry into which is usually achieved through patronage (Crane 1972). Publications in scientific journals, the major social mechanism for disseminating and producing scientific knowledge, must bear the stamp of authenticity from editors and referees (Ziman 1968:111). "Contributing" to journals can be analyzed anthropologically as a gift-giving practice, with social recognition as an expected consequence (Hagstrom 1965). 9 Sociologist Robert Merton demonstrates that the failure to credit previous work threatens the social system of incentives within science (1957). Thus, power dynamics permeate science as a social institution.

Jean-Franćois Lyotard contends that the goal of scientific debate is dissension, not consensus (1984:60–66). As one physicist puts it, "The game is, you try to smash everybody else's theory" (Hagstrom 1965:31). Indeed, this is how new theories come about. Foucault's notion of power applies to science: theories, like other power centers, generate resistance. By erecting locales of resistance, scientific discourse provides the context not only for its progress but also for its delegitimation. The denotative statements of science must ultimately be legitimated in terms of a second-level narrative discourse, which opens the door to struggle around principles of good theory construction. According to Lyotard, "what we have here is a process of delegitimation fueled by the process of legitimation itself. The 'crisis' of scientific knowledge, signs of which have been accumulating since the end of the nineteenth century, . . . represents an internal erosion of the legitimacy principle of knowledge" (1984:39–40). Lyotard reiterates Nietzsche's argument that European nihilism follows from the truth requirement of science being directed against itself. This process of dissension and delegitimation is especially evident in the policy arena, where claims are met with counterclaims and research seems to be self-propagating.

While accepting that science is a social activity, however, I want to avoid a wholesale relativism. For radical social constructivists, science is merely epiphenomenal to social factors. Yet while science is an inescapably social process involving persuasion and power relations, it also can tell us something about how the natural world works. At first glance, this may seem like a precarious balancing act, but such a middle position generates a conception quite consistent with our intuitive understandings of science.

The failure to respect the fundamental distinction between ontology, which studies the nature of existence, and epistemology, which studies the nature of knowledge, has been a major source of misunderstanding between objectivists and relativists. As they talk past one another, the former seem to claim that knowledge faithfully reflects reality, and the latter seem to say that all knowledge is arbitrary. A more balanced view is that objects and events actually exist and that our knowledge has something to do with them. This is the basis of an ontological realism and a hermeneutical, yet pragmatic, epistemology.

Roy Bhaskar argues that every fact comprises both "transitive" and "intransitive" associations (1989). The former derive from psychological, social, and historical factors, and the latter from ontological reality. For example, the assignment of the atomic weight of 16 to oxygen is an arbitrary, or transitive, convention. Once this convention is established, the atomic weight of hydrogen is inevitably 1.008; this inevitability constitutes an intransitive dimension. Scientific progress is marked by an increase in both the transitive and intransitive aspects of facts.

For Bhaskar, recent philosophy of science is paradoxical. While the fundamental assumptions of positivism lie shattered, alternative accounts of science cannot sustain a coherent notion of the rationality of either scientific change or the nondeductive component of theory. He traces this difficulty to an ontology incompatible with recent constructivist accounts of science. The Humean view of causality as constant conjunctions of events rests upon a mistaken conflation of causal laws with their empirical grounds (1989:11–17).

In his alternative ontology, transcendental realism, Bhaskar tells us that in order for experimental activity to be intelligible, the world must contain actual structures. Though he does not presume to say how the world is structured, for that is the scientists' task, he argues that science moves from knowledge of manifest phenomena to knowledge of the structures behind them (1989:20). He challenges both the Humean identification of causal laws with patterns of events and the Kantian (transcendental idealist) conceptual framework (1986:38–50). Rather than being based on constant conjunctions, a priori constructs, or social factors, the laws of gravitation, thermodynamics and electromagnetism are rooted in the structures of nature.

Bhaskar's account of scientific knowledge is neither objectivist nor relativist. While he does not not explore the social dynamics of science in any detail, for he is trying to fill a critical gap in the philosophy of science by constructing a consistent theory of being, he nonetheless is clear that science is a social process. He refers to it as "a produced means of production" and "a practical labor in causal exchange with nature" (1989:21). Yet Bhaskar rejects a pure hermeneuticism, which reduces knowledge to discourse, thereby presenting an anthropocentric view of nature while failing to offer an adequate account of human agency. Such a view, he claims, is not only wrong but socially irresponsible in failing to recognize the real constraints on people's actions (1989:153).

The transcendental realist ontology can be enhanced by an epistemology that explicitly links knowledge with power. Like Bhaskar, philosopher of science Joseph Rouse is troubled by the postpositivist focus on the theoretical dimensions of science, which emphasizes the epistemic success of science rather than its practical success. Instead, Rouse understands the sciences "not just as self-subsistent intellectual activities but as powerful forces shaping us and our world" (1987:ix; emphasis added). For Rouse, science is a deeply practical activity that transforms both the world and how the world is known; its power lies not so much in the representational accuracy of its theories as in the functional skills it deploys. The entire planet has been physically transformed by these skills.

While portraying science as a consensual activity, Rouse adopts a much broader Foucaultian conception of power than do the pragmatists, who remain wedded to the idea that power is repressive and partisan, i.e., an obstacle to consensus rather than a facilitator of it. This approach allows Rouse to sidestep their search for a mode of inquiry unconstrained by the effects of power, although he recognizes the repressive effects on science of certain applications of juridical power. Like the new empiricists, Rouse redirects the locus of knowledge from accurate theorizing to the manipulation and control of events. He goes further, however, in linking this ability to power. The reason science can control nature is that it works with the intransitive structures that must exist if experimental activity is to be understood as intelligible. Thus, it is not surprising that laboratory experiments seem to reveal something about the world; scientists work hard to make them relevant to one another.

Rouse regards the laboratory, the distinguishing expression of science as an institution, as an embodiment of disciplinary power. The laboratory is not just a physical space bounded by four walls but "a context of equipment functioning together, which even incorporates nature among that equipment" (1987:107). In the laboratory, scientists labor to create phenomena; the objects they study are less "natural" events than the products of artifice (Latour 1983:166; quoted in Rouse 1987:23). He compares the laboratory to the school, the asylum, the factory, and the prison, all of which are "blocks" within which a "microphysics of power" is developed and reaches out to shape the surrounding world. 10

At first glance, the power that arises from science seems qualitatively different from more narrowly conceived notions of power; the former is rooted in power over natural phenomena whereas the latter entails power over people. This dichotomy, however, is based upon three misconceptions. First, it rests upon a rigid and unacceptable dichotomy between nature and human beings. Second, it ignores the productive and generative aspects of power. Third, and more important for the following discussion of the political implications of knowledge-based power, such a dichotomy ignores the profound degree of interdependence between the two sorts of power. The power of scientists to interpret reality has itself become a productive source of political power, regardless of how knowledge gets translated into technology. Scientists' power derives from their socially accepted competence as interpreters of reality. Yet they are not simply powerful agents wielding an arsenal of knowledge; rather, discourse itself is a source of power, facilitating the production of identities and interests.

Experts and Scientific Discourse in Politics

The belief in the power of science to improve human life is perhaps the quintessential hallmark of the modern era. From the sixteenth century onward, and from left to right across the political spectrum, Western thought has been characterized by an overarching faith in science (Bacon 1889, 1974; Condorcet 1976; Saint-Simon 1952; Comte 1986; Popper 1966). Many of modernity's seminal thinkers have located science in a realm outside power relations, hoping that it might someday provide an objective basis from which to supplant or transform political discourse. Even today this belief, with its implicit dichotomy between knowledge and power, is not uncommon. Science is conceived as a realm of objective facts, divorced from political considerations of "tradition, prejudice and the preponderance of power," from which rational and optimal policy decisions can be forged (Kaplan 1964:24). The "estates" of science and politics, oriented toward truth and power respectively, have generally been conceived as utterly distinct (Price 1965).

Yet, in the shadow of technology-related disasters, including this century's wars of unprecedented destruction, the modernist faith in the ability of science to order human affairs is waning. In many ways, the environmental movement is an ironic expression of this skepticism, calling into question the effects of science and technology while at the same time relying upon scientific discourse to make its case. If discourses are themselves power centers, as Foucault suggests, then we should expect to find resistance to the modern faith in science. Thus, there is a tributary diverging from the mainstream that portrays science more dubiously as Frankenstein's creation or Pandora's box. This undercurrent, typified by the nineteenth-century Romantics, has grown in popularity as the negative effects of science and technology have made themselves felt. Hans Morgenthau, writing at the close of World War II, opens his Scientific Man vs. Power Politics with the following: "Two moods determine the attitude of our civilization to the social world: confidence in the power of reason, represented by modern science, to solve the social problems of our age, and despair at the ever-renewed failure of scientific reason to solve them" (1946:1).

The two faces of science are a subspecies of the two faces of persuasion. On one side is the rational ideal, which overstates the purity of information and exaggerates the rationality of those employing it; on the opposite side is the ugly face of propaganda (Stone 1988:249). Yet if knowledge production is a social process and interpretation is more important than fact in the policy arena, then the dichotomy is illusive. Since knowledge is inseparable from power even in pure science, the links should be even stronger when science is implicated in policy problems. Alvin Weinberg states: "Many of the issues which arise in the course of the interaction of science or technology and society - e.g., the deleterious side effects of technology, or the attempts to deal with social problems through the procedures of science - hang on answers to questions which can be asked of science and yet which cannot be answered by science (1972:209; emphasis in original).

Weinberg has popularized the term "trans-scientific" for this category of increasingly common policy questions, such as the probability of extremely improbable events and the application of engineering judgment in technology design. (Regulation of ozone-depleting chemicals and greenhouse gases are specific examples of trans-scientific policy problems.) I would argue that trans-scientific discourse derives its influence from three sources: the authority of its agents, the political context in which it is situated, and the cogency of its content. This section examines the first of these, scientific experts as discursive agents in the policy arena, and the following section turns to the second and third, the contextual and substantive constitution of discourse.

The importance of expert advice in shaping policy decisions is nothing new. In the past, advice came from such sources as oracles and prophets, although rational calculation and the equivalent of cost-benefit analysis have existed since ancient times (Goldhamer 1978:129–31). Expert advice has often pertained to military matters, a trend that has continued up to the present. 11 More generally, turbulent political conditions, characterized by complexity and uncertainty, induce decision makers to seek greater clarity and predictability through consultation with advisers. Contemporary turbulence is characterized by an increase in international interdependence and a greater connection among policy issues (Rosenau 1989; Keohane and Nye 1977); thus expert advice is increasingly sought in addressing international problems.

Though my focus is knowledge-based power, I do not want to exaggerate its importance. The influence of experts is limited; they do not replace the existing political process. Information is always relayed and exchanged in the larger political arena - ultimately, experts can be fired or become pawns. They may also become pawns, their prestige used to legitimize policy objectives not directly relevant to their areas of expertise, as when scientists were mobilized in support of the Atmospheric Test Ban Treaty during the Kennedy administration (Uyehara 1966). Disagreement among experts can also be used as an excuse to ignore their advice, as was the case for many years with the acid rain issue and, until the Clinton administration, with the global climate change question as well.

Despite these limitations, the ability to interpret reality allows experts to wield real power. Policymakers who ignore experts or conceal facts risk political embarrassment, particularly in pluralistic societies where scientists speak out publicly. Scientists are likely to find allies in the media, since both science and the media seem to have an innate distrust of political and economic elites (Wood 1964:59). Political leaders also risk embarrassment when their ignorance of important scientific information is exposed, as happened more than once during the Montreal Protocol process. But the most important source of power for experts, even when they disagree, is the fact that without them policymakers are more likely to make bad decisions. In the words of one author, "to assume that technical inputs are unimportant because both sides of a controversy commonly present technical analyses purporting to prove their own side of the issue is a little like a judge deciding the facts of a case are unimportant because the lawyers on each side always present briefs purporting to show how the facts support their own client" (Margolis 1973:51).

The discursive worlds of experts and policymakers are inherently different, leading to the possibility of mutual misunderstanding and mistrust. Experts often deal in abstractions within their narrow specialties, whereas politicians must be attentive to specific circumstances and how various interests will be affected by their decisions. Policymakers may be uncomfortable with experts' neglect of the economic consequences of their recommendations, as often happens in environmental politics. Experts may be uneasy in the world of compromise and pork barreling, and they may be ignorant of their own political influence. Policymakers may be awestruck by technical language, leading them to develop unrealistic expectations of what expert advice can accomplish. They may also resent experts for their occasional pedantry, or they may lose patience with technical detail. Decision makers are also liable to ignore significant aspects of advice, suffering from the general human proclivity to believe that what one does not understand must not be very important (Margolis 1973:50). The two faces of science - overstatement and propaganda - also surface in the policy context; nonscientist policy actors have been known to complain of "the cult of doctor worship" (Wood 1964:43).

A related problem is the different time frames within which experts and policymakers work. Experts can help expand the time horizon to anticipate policy implications. Yet their analyses may be unwelcome in political circles, where the ability to stay in power depends on relatively short-term considerations. This is a major issue for global environmental problems, whose full effects may not be felt for generations.

As with other forms of power, success breeds success for knowledge-based power. 12 Experts do not deal simply with facts; they must cultivate their reputations as sources of authoritative knowledge. In this area, rationality takes the back seat to power and trust. The ability of experts to reduce uncertainty depends in part on whether they are perceived as powerful or trustworthy, particularly during crises, when experts who save the day may modify existing power structures by displacing others. Yet experts also are trusted only inasmuch as they succeed in reducing uncertainty. Thus, power is generated in a circular fashion. A good example is the prestige the National Aeronautics and Space Administration obtained through its successful Apollo program, contrasted to the sharp decline in public trust after the Challenger disaster.

Because of their access to specialized knowledge, scientists are uniquely situated to place certain issues on the public agenda. Scientists were the first to point out the potential to build atomic weapons, the unresolved problems of nuclear waste disposal, the dangers of recombinant DNA research, and the ecological threat of DDT. In most cases, however, they must rely on coalitions with public officials, interest groups, and bureaucracies to implement their policy proposals. But unlike the search for knowledge, which is accepted as a legitimate practice, the search for allies must be disguised by other professional activities (Benveniste 1977:149). Ultimately, this necessity is rooted in the larger belief that science is objective and value-free, while political life is ideological and value-laden. While that view, as I have argued in the previous section, is faulty because facts are socially constructed, it is nonetheless influential.

But the fact-value dichotomy and the resultant split between science and politics raise other problems in a policy context. First, if the dichotomy were pure, scientists would never call attention to a problem, for to do so would betray a commitment to certain values. But why did Einstein urge President Roosevelt to develop atomic weapons? And why should a researcher point out that a certain chemical might cause cancer? For the simple reason that they care and are committed to specific values. At a minimum, they believe in the value of their own information, and they are concerned with how their recommendations are received. Second, both scientists and policymakers recognize that not all facts are of equal value, for they vary in their interest and productivity, as well as in their internal robustness (Ravetz 1986:421). Third, data does not stand on its own; it must be interpreted, and it is frequently interpreted according to preexisting value commitments.

Further dividing the two worlds are the different modes of factuality involved. Kratochwil's description of "the three worlds of facts" is relevant here (1990:21–27). Scientists generally operate in the world of observational facts, while policymakers deal primarily with intentional and institutional facts. Scientific facts are subject to validation tests very different from those for political facts. If the public believes something to be true, even if science has shown it to be false, that belief remains an important fact for policymakers. Similarly, if the fact-value distinction is fallacious, the perception of its validity can influence the politics of technical advice.

Scientists who perceive their own work as by definition value-free in its approach and beneficent in its results can easily delude themselves about their own political involvement. A better impetus for unfettered political activity can scarcely be imagined than the belief that one's preferences derive from objective reality (Wood 1964:63). 13 The potential for self-deception is consistent with my earlier argument that power is not inherently intentional. Most scientists, even those who work in policy-relevant areas, do not see themselves as seeking power. Nor do their more overtly political counterparts, for the belief in the objectivity of science is deeply entrenched.

Facts must be communicated verbally, and the choice of words is itself a value choice. One example is whether risk is stated in terms of absolute or relative risks. The same exposure to a toxic chemical may be expressed either as a one-in-a-million risk per year or as a 5 percent increase over normal background rates (Wynne 1987). Clearly, the second sounds more serious. As I shall show, certain modes of framing the facts were vital in negotiating the international ozone agreements.

Ideological goals can also be pursued and legitimated through science. Judgment calls are frequently required when technical questions lie at the heart of decision making; more than one solution is usually justifiable on scientific grounds. A good example is how the Reagan administration's political goal of deregulation was implemented by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Decision rules regarding carcinogens included the following: animal studies were not necessarily relevant; benign tumors need not be considered damage; and merely looking at the chemical structure of some substances could suffice to determine their carcinogenicity. These interpretations of scientific rules of inference show that "there is a significant area in which science and policy are not separable - they organically interpenetrate one another" (Wynne 1987:108–9). While all these rules are technically defensible, the outcome is a policy rooted in ideology.

Proponents of risk analysis argue that the so-called scientific functions of risk assessment should be separated from the political process of risk management (Environmental Forum 1984). Risk analysis has been attacked on epistemological, ethical, and political grounds. 14 Among other things, it is called to task for reducing all values to economic values, for assuming linearity in calculating risks, and for failing to recognize the value-ladenness of certain techniques such as discounting the future. All these criticisms add up to the failure of risk analysis to recognize that the science of risk assessment is really trans-scientific. 15 If even the purest science cannot be wholly extricated from social and political considerations, then it is unwise to have such expectations for environmental and other science-based policy problems.

Recent research on risk perception and decision making under uncertainty point to major flaws in the rationality assumption. People tend to employ a number of general inferential rules, or heuristics, in evaluating risks (Tversky and Kahneman 1981). One such judgmental bias, "availability," predisposes individuals to overestimate risks resembling ones they have encountered recently and to ignore risks that they have never experienced. Thus, the likelihood of unprecedented environmental change, such as extreme changes in local climate or severe ozone depletion, is often discounted in spite of dire scientific predictions. A related heuristic is the "out of sight, out of mind" bias (Fischhoff, Slovic, and Lichtenstein 1982). People tend to accept that the data in front of them must represent all the possibilities. These heuristics are particularly pernicious because people tend to be overconfident about decisions based on them, a tendency just as prevalent among experts as among laypersons.

The rationality assumption is also undercut by the importance of framing in policy discourse. Frames, which are fundamental in discourse, are analogous to varying visual perspectives on the same scene; the apparent size of an objective, for instance, varies with the observer's distance from it. A frame is also a boundary that cuts off something from our vision (Stone 1988:198). Contrary to experience, rationality requires that changes of frame should not alter one's preferences. Tversky and Kahneman uncover some fascinating instances of the framing problem. They find, for instance, that for most people choices involving gains are often risk averse and choices involving losses are often risk taking, even when a problem can be framed either way (1981:453). Other research reveals that people prefer insurance that covers specific harms fully over policies covering a wide range of harms conditionally, even if the latter would be a more "rational" choice (Kunreuther 1978). Apparently, insurance is "bought against worry, not only against risk, and worry can be manipulated by the labeling of outcomes and the framing of contingencies" (Tversky and Kahneman 1981:456). An action increasing one's annual risk of death from 1 in 10,000 to 1.3 in 10,000 is perceived as far more hazardous when framed as a 30 percent increase in mortality risk (Fischhoff, Slovic, and Lichtenstein 1982:479). These findings have important implications for environmental policy, which is inherently probabilistic. In fact, international environmental treaties have been regarded by negotiators as insurance policies (U.S. Department of State 1986).

Debates about values and norms are typically couched in empirical terms. Seldom does a person rest her case for a particular policy on mere subjective preference; rather, she buttresses her position with facts. For this reason, no matter what values underlie a controversy, the debates generally focus on technical questions; questions of value become framed as questions of fact. Since science is modernity's preeminent instrument of legitimation, all participants can be expected to claim that their positions are mandated by science, even if science alone can never mandate anything. Power hinges on the ability to deploy knowledge, with the result that political values and scientific facts become difficult to distinguish.

The increasing amount of reference to science seems to be accompanied by its decreasing credibility. Policy science is paradoxically a scarce resource, in spite of its exponential growth. When debates are framed in scientific terms, each confrontation may undermine the credibility of the positions and lead to the search for more scientific weapons. Expertise generates counterexpertise (Benveniste 1977:147), particularly in pluralistic societies. Lyotard's epistemological argument that the demand for legitimation results in a process of delegitimation is mirrored in the policy world.

I do not mean to imply that science is so hopelessly mired in political questions that it is of no help in depoliticizing issues; I simply want to claim that the waters are muddier than is generally appreciated. Still, just as I would want judges to read their briefs, I hope that policymakers listen to scientific advice. Science may depoliticize certain issues to some small extent, for two reasons. First, as I have argued above, facts have both fixed and conventional dimensions, and the former are axiomatically apolitical, even if their implications are sources of considerable political controversy. Either chlorofluorocarbons destroy stratospheric ozone, or they don't; the question is not answerable in polemical terms. Second, inasmuch as policymakers believe that science is apolitical, they may be willing to use it to build a policy consensus. But such an outcome is likely only if there already exists a strong impetus toward political consensus.

Neither do I mean to suggest that all forms of power are reducible to discursive power. Scientific discourse is circumscribed by juridical forms of power. While national interests may be shaped by expert advice, once those interests are determined, more traditional forms of state power come to the fore. Science is entwined with state power in another important respect: scientists are also citizens. National governments are often reluctant to accept "foreign science," and despite the cosmopolitan culture of science, scientists do not generally relinquish their national identities.

Environmental issues inject distinctive temporal and spatial understandings into the policy process, tendencies that are amplified as the problems take on intergenerational and planetary proportions. One factor that is both cause and effect of this spatial and temporal expansion is the emergence of new policy actors: a network of scientific and technical experts, including "risk professionals," with access to specialized knowledge (Dietz and Rycroft 1987). 16 Because of the highly specialized nature of much of the relevant "pure" science, another important intermediary category of actors has entered into the environmental policy-making process. These people are not themselves researchers but have the skills needed to understand the work of academics and other researchers. Typically, they also have a flair for translating that work, identifying the policy-relevant angles in it, and framing it in language accessible to decision makers. James Sundquist calls them "research brokers," citing as an example the U.S. President's Council of Economic Advisers (1978:130). I prefer the term "knowledge brokers," because it highlights the broad range of information that is translated and underscores that interpretation is more important than fact. Implicit in the term is the recognition that injecting science into policy is itself a political act requiring a strategy of information transfer (Caldwell 1990:23).

Knowledge brokers can exist at lower levels of government, as did the small group of EPA policy analysts who kept the ozone issue alive both domestically and internationally for years. Nongovernmental actors, including social movements and businesses, can also function as knowledge brokers, framing and translating information not only for decision makers but also for the media and the public. Thus, while scientific knowledge is an important source of power, scientists are not the only ones with access to it; once produced, knowledge becomes something of a collective good, available to all who want to incorporate it into their discursive strategies.

Scientific Discourse in the Policy Arena

As determinants of what can and cannot be thought, discourses delimit the range of policy options, thereby serving as precursors to policy outcomes. The emphasis on discourse calls into question the traditional focus on agents without reverting to structure as the ultimate explanatory factor (Wendt 1987; Dessler 1989). This epistemological shift moves away from the standard schism between subject and object (decision maker and decision situation) toward a recognition that subjects are at least partially constituted by the discursive practices and contexts in which they are embedded (Shapiro, Bonham, and Heradstveit 1988:398).

One should not understand this epistemological shift as a wholesale elimination of the subject, despite the language of some poststructuralists. Rather, what is entailed is the decentering of the subject, engendered by a refocusing of one's methodological lenses on the study of discursive practices rather than agents. Just as power necessarily entails some degree of subjectivity, even if only in contingent form, so too do discursive practices. Discourses could not exist without individuals and groups promoting them, identifying with them, and even struggling with them. Discursivepractices are inconceivable without discursive agents, coalitions, and knowledge brokers.

Yet the overarching regulation of the political field by codes, specifically linguistic codes, "transcends the generative and critical capacities of any individual speaker or speech act" (Terdiman 1985:39). The supreme power is the power to delineate the boundaries of thought - a feature of discursive practices more than of specific agents. What becomes important, then, is how certain discourses come to dominate the field and how other, more marginal counterdiscourses establish networks of resistance within particular "power/knowledges" or "regimes of truth" (Foucault 1980).

Discursive power is decentralized, nonmonolithic, and linguistically rooted. All discourses, including hegemonic ones, are, in Mikhail Bakhtin's words, "heteroglot." They represent: "the co-existence of the socio-ideological contradictions between the present and the past, between differing epochs of the past, between different socio-groups in the present, between tendencies, schools, circles and so on" (Bakhtin 1981:291; quoted in Terdiman 1985:18–19). Networks of resistance operate perpetually among dominant discourses and subjugated knowledges. Because counterdiscourses are always intertwined with the hegemony they oppose, the two stand in a necessary relation of "conflicted intimacy."

In much social science research, context is marginalized as a backdrop against which the real drama takes place. But with a turn toward discursive practices, the pervasive nature of context becomes evident. Meanings are shaped by context, and "the frame comes unexpectedly to define the center" (Terdiman 1985:17). For environmental problems, disasters and crises are often the contextual factors that serve as a kind of mold within which accepted knowledge is cast, thereby permitting hitherto rejected ideas to gain a hearing.

Deborah Stone discusses the forms of symbolic representation that

characterize policy discourse (1988:108–26). "Narrative stories" are

emotionally compelling explanations of how the world works, featuring

heroes, villains, and innocent victims (which need not be human). Stone

cites two broad story lines: a story of decline and a story of control.

The former recounts the undoing of an earlier, superior situation,

calling for policy action to reverse this decline. The latter suggests

that a problem that was previously seen as inevitable, natural, or

accidental is actually solvable through human action. Both story lines

are bolstered by facts, and both are compelling in as much as they point

to deliverance from decline or the promise of control. The two are

frequently woven together, as they were in the ozone negotiations.Policy stories, including those told in scientific terms, use

rhetorical devices to persuade the audience. Metaphors, which employ a

word that denotes one thing to describe another, frequently take a

"normative leap" from description to prescription (Rein and Schon 1977;

cited in Stone 1988:118). The discourse on nuclear weaponry is rife with

such metaphors. The terms "ozone layer" and "ozone hole" are both

metaphors, the latter having a strong emotional charge. The term

"greenhouse effect" is another metaphor, one with favorable overtones:

greenhouses are pleasant places to grow tropical plants (although those

who work in them can testify to the oppressiveness of the environment).

One climate scientist urges that the metaphor be abandoned because it

cannot motivate action, suggesting that it be replaced with a term like

"global heat trap" (Schneider 1989:58).

Interpretive repertoires may also employ synecdoche and metonymy,

whereby apparently particular phenomena are integrated into a whole or a

whole is reduced to one of its parts (White 1978). The global warming

problem, as enormous as it is, has been taken by some environmentalists

as a symbolic representation of the "end of nature" (McKibben 1989), an

application of synecdoche. Attempts to address the climate change problem

through partial solutions, whether through CFC regulation or saving the

rain forests, are metonymical moves. The discursive strategy to reduce

ozone depletion to a skin cancer problem also employs the rhetorical

trope of metonymy.

The belief that scientific knowledge can yield policy decisions

without the intervention of rhetorical strategies is part of what Stone

calls the "rationality project," which attempts to "public policy from

the irrationalities and indignities of politics" (1988:4). The misguided

identification of science as a tool for ending political dissent is part

of that project. Science itself, in seeking to persuade an audience

through language, is a rhetorical activity, even when it conceals its

rhetorical aim; factual description is a seemingly

innocuous and uncontroversial activity. In the policy world, "advocacy

science," which proceeds through the "strategic orchestration of

scientific arguments," is even more clearly rhetorical (Ozawa 1991).

Framing, heuristics, and other rhetorical strategies are all defining

elements of particular discourses. But they are not disembodied

phenomena; they require human agents for their initiation, application,

and dissemination. Discursive coalitions and knowledge brokers employ

their strategies in a web of power relations, and those strategies become

implicated in and constitutive of that web.

Conceptions of Science in International Relations: Functionalism,

Neofunctionalism, and Epistemic Communities

All the problems inherent in the politics of technical advice are

replicated in international policy coordination, with the added

complication of interstate rivalry. Earlier I argued that the power of

technical experts is proportional to the trust that decision makers have

in them. This problem arises with a vengeance in international relations,

an arena characterized by inherent distrust. Governments are far more

likely to pay attention to studies done within their own borders than

those from other countries. International organizations and, in some

cases, scientists themselves, have sought to alleviate this problem by

conducting studies and evaluations through independent international

panels, the United Nations' specialized agencies, and regional

organizations. Nevertheless, governments often insist on doing their own

studies, and in the end they may not even listen to their own scientists.

Too, if the stakes are high, there is even more incentive to disregard

the science.

On the one hand, there is some validity in the widespread belief that

"science forms the most truly international culture in our divided world"

(Brooks 1964:79). International conferences and journals are the main

channels through which scientists communicate new ideas and discoveries.

Even at the height of the Cold War, scientists on both sides of the Iron

Curtain were calling for greater openness, not just for political reasons

but to further their own work. In addition, to the extent that scientists

are committed to universalism and communality (Merton 1973:263–64), there

is reason to see science as a potential unifying force in international

conflicts over technical issues. On the other hand, the political

dynamics of technical advice indicate that an untempered

optimism in the cosmopolitan nature of science may be misplaced. The hope

that science can harmonize international politics is not completely

groundless; unfortunately, however, it is often accompanied by a naive

view of knowledge as separate from power, as well as a poor understanding

of the complexities involved in translating scientific knowledge into

policy.

In this section, I look at three theoretical approaches to science in

politics at the international level: functionalism, neofunctionalism, and

the literature on epistemic communities. Unlike the dominant theories of

world politics, which focus on military and economics sources of power,

these approaches recognize the importance of cognitive factors -

knowledge, ideas, and beliefs - in shaping events and outcomes. Yet each

of these approaches tends to divorce knowledge from power, and they all

fail to appreciate fully the discursive nature of science. They are, to

varying degrees, part of the rationality project.

Functionalism has its historical roots in nineteenth-century thinkers

as diverse as Saint-Simon (1952), Herbert Spencer (1896), and the Fabian

Socialists (Woolf 1916). It is sometimes a descriptive or predictive

theory and sometimes a normative theory; it evinces a modern faith in

technical rationality. Kenneth Thompson cites the defining

characteristics of functionalism: it is nonpolitical, involving social

and economic issues, addressed to urgent problems, undertaken in a

problem-solving manner, and built upon the cooperation of professionals

(1979:96–99). Technical experts are expected to steer the way to a

functional world by virtue of their ability to fashion a consensus on

means-ends relationships.

Most representative of the recent literature is David Mitrany, who

foresees that, as the nation-state's ability to protect the welfare of

its citizens decreases because of the interdependence of nations and

issues, power will be ceded to functional international organizations

(1975). Although Mitrany's focus is economic, environmental problems are

also of universal concern and may even fit his theory better, since

knowledge in the natural sciences is more consensual than in the social

sciences. A major problem, however, is that Mitrany assumes both expert

consensus and technical certainty, assumptions that disregard the

discursive nature of knowledge. Mitrany, like so many others, portrays

experts as above the fray of social and political conflict and has a

purely negative conception of power. 17 Ernst Haas criticizes Mitrany on these

grounds: "The peace of statesmen, of collective security, of disarmament

negotiations, of conferences of parliamentarians, of sweeping

constitutional attempts at federation, all this is

uncreative. It is so much power instead of creative work" (Haas 1964:12).

Another problem with functionalism is its deterministic assumption of

historical efficiency. Mitrany assumes that social processes are

rational, holding that a community-building consensus will inevitably

develop in a context wider than the specific issue area addressed by a

functional organization. Functionalism cannot say how this development

will come about; it has no theory of social change because it lacks a

theory of agency. 18

In his first major work, Ernst Haas (1964) attempts to amend

functionalism by proposing a more empirically relevant, less ideological

neofunctionalism. In his two case studies on the World Health

Organization and arms control, Haas finds that the predictions of

functionalism do not withstand scrutiny. In the former, he sees no

attempt to delineate political and technical concerns clearly. In the

latter, experts were important, but they frequently pursued

nationalistic, not universalistic, objectives.

Haas argues that functionalism's main shortcoming is that it has no

theory of interests and so must resort to the utopian notion of the

common good as the motivation for action. Ignoring the role of interests

in international cooperation, functionalists attribute cooperation to

manipulative experts working for the common good. For Haas, any claim

represents an interest, interests need not be consciously shared in order

for integration to take place, and integration can occur under conditions

of competition as well as cooperation. Unlike Mitrany, Haas provides an

account of how authoritative decisions can be made even when experts

disagree among themselves. Likewise, he can account for at least some

unintended consequences of actions.

Unfortunately, Haas's conception of interest is truncated. If each

claim constitutes an interest, then Haas cannot differentiate between

interests and delusions. Nor does Haas adequately link his notion of

interest to Mitrany's notion of function. In his concern to distinguish

his own more "scientific" work from the overly normative functionalism,

he offers no basis for the performance of functions other than the growth

of organizations. Functionalism, with its normative bias, at least

grounds its prescriptions in the desirability of meeting human needs.

Haas also takes issue with the assumption of inevitable spillover

effects, pointing out that functionalism offers no theory of how this

development comes about. His less deterministic neofunctionalism attempts

to solve this problem by using the process of "social learning" to

account for international community building. Haas interprets

functionalism as a development from gesellschaft to gemeinschaft, or from

an elite community to a network of societal associations. 19 Haas's

neofunctionalism, like its precursor, evades issues of

power. He does not give sufficient credence to the possibility that

scientists may constitute an elite class with a monopoly on information.

Nor does he consider that expert advice may simply reinforce existing

power relations among states, rather than move the international

community "beyond the nation-state." Like Mitrany before him, Haas, at

least in his early work, succumbs to the modernist fallacy: he drives a

wedge between knowledge and power, dislodging expert advice from the

realm of politics.

In his later works, Haas is more aware of this problem, though he

continues to adhere to the same misconception on a more subtle level. In

Scientists and World Order (1977), he and his coauthors specifically

consider whether the introduction of science into international politics

indicates progress toward a more rational and cohesive world order. On

the one hand, they recognize that science has not brought about the end

of ideology and that it will never be able to do so inasmuch as it cannot

settle questions of ends. They admit that scientists suffer from

sociological ambivalence. They draw no rigid line between the technical

and political but rather propose a continuum from the "purely technical"

to the "purely political."

he offers no basis for the performance

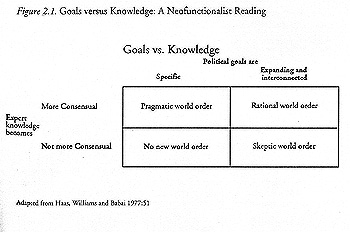

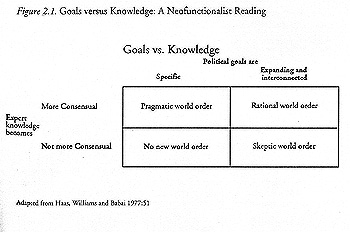

On the other hand, much of their work seems to be rooted in contrary

principles, particularly their depiction of knowledge as the independent

variable and world order as the dependent variable. While claiming that

their taxonomy in a two-by-two matrix is merely a heuristic device, their