The Genus

Paranthropus

P. boisei

P. aethiopicus

P. robustus

P. boisei

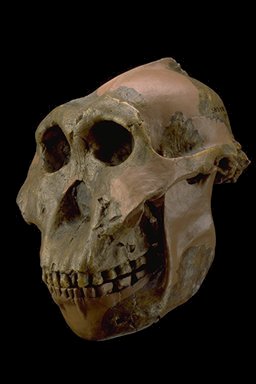

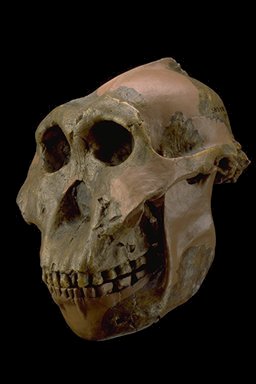

Paranthropus boisei was first discovered by Mary Leaky in 1959, and

was first termed Zinjanthropus boisei or Zinj. The oldest

Paranthropus boisei was found at Omo, Ethiopia and dates to approximately

2.3 million years ago, while the youngest was found at Olduvai Gorge, and

dates to approximately 1.2 million years ago. P. boisei is best

known for its enormous postcanines, and seems to be the end point of a lineage

that was adapted to high masticatory stress needed to deal with hard low-quality

foods. One theory is that P. boisei died out because of overspecialization

to a specific environment, which prohibited it from adapting to a rapidly

changing environment and climate. Compared to other robust species,

P. boisei has a larger cranial capacity (500-550 cc), a more vertically

set face, and a sagittal crest on the mid-brain case, as opposed to the posterior.

It is widely accepted that P. boisei’s ancestor is A. africanus

. The discovery of P. boisei was important because it disproved

Milford Wolpoff’s “Single Species Hypothesis" that was so popular in the

1960s. This hypothesis stated that every environmental niche could

only support one species. Following his logic, P. robustus

was thought to be made up of all males, while A. africanus was thought

to be made up of all females. Because P. boisei of both sexes

were found in the same site and were dated to the same time, the discovery

proved that even if the South African material was a single sexually dimorphic

species, P. boisei was a different species contemporary with it,

bringing into doubt the validity of the single species hypothesis.

Paranthropus boisei was first discovered by Mary Leaky in 1959, and

was first termed Zinjanthropus boisei or Zinj. The oldest

Paranthropus boisei was found at Omo, Ethiopia and dates to approximately

2.3 million years ago, while the youngest was found at Olduvai Gorge, and

dates to approximately 1.2 million years ago. P. boisei is best

known for its enormous postcanines, and seems to be the end point of a lineage

that was adapted to high masticatory stress needed to deal with hard low-quality

foods. One theory is that P. boisei died out because of overspecialization

to a specific environment, which prohibited it from adapting to a rapidly

changing environment and climate. Compared to other robust species,

P. boisei has a larger cranial capacity (500-550 cc), a more vertically

set face, and a sagittal crest on the mid-brain case, as opposed to the posterior.

It is widely accepted that P. boisei’s ancestor is A. africanus

. The discovery of P. boisei was important because it disproved

Milford Wolpoff’s “Single Species Hypothesis" that was so popular in the

1960s. This hypothesis stated that every environmental niche could

only support one species. Following his logic, P. robustus

was thought to be made up of all males, while A. africanus was thought

to be made up of all females. Because P. boisei of both sexes

were found in the same site and were dated to the same time, the discovery

proved that even if the South African material was a single sexually dimorphic

species, P. boisei was a different species contemporary with it,

bringing into doubt the validity of the single species hypothesis.

P. boisei

More Boisei

P. aethiopicus

Because of a lack of archaelogical evidence, there is very little known

about Paranthropus aethiopicus. However, it is generally accepted

that P. aethiopicus falls somewhere between the “robust” and “gracile”

australopithecines. The first specimen of P. aethiopicus was found

by a French expedition led by Camille Arambourg and Yves Coppens in southern

Ethiopia in 1967. P. aethiopicus was named a new species partly

because of its V-shaped jaw, which was different from other robust australopithecus

known to have lived in the area. The most famous specimen of P.

aethiopicus was discovered west of Lake Turkana and was dated to 2.5

million years old. It was known as “Black Skull” because mineral uptake

during fossilization gave the specimen a blue-black color. The “Black

Skull” specimen is similar to a male A. afarensis, but has a very

small cranal capacity (410 cc) and a more developed masticatory apparatus.

Like A. afarensis , A. aethiopicus has a flattened cranial

base and large anterior tooth sockets. A. aethiopicus was shown

to be the possible base of the boisei lineage; more primitive than robustus

yet not ancestral to it. There is, however, much debate about this.

Because of a lack of archaelogical evidence, there is very little known

about Paranthropus aethiopicus. However, it is generally accepted

that P. aethiopicus falls somewhere between the “robust” and “gracile”

australopithecines. The first specimen of P. aethiopicus was found

by a French expedition led by Camille Arambourg and Yves Coppens in southern

Ethiopia in 1967. P. aethiopicus was named a new species partly

because of its V-shaped jaw, which was different from other robust australopithecus

known to have lived in the area. The most famous specimen of P.

aethiopicus was discovered west of Lake Turkana and was dated to 2.5

million years old. It was known as “Black Skull” because mineral uptake

during fossilization gave the specimen a blue-black color. The “Black

Skull” specimen is similar to a male A. afarensis, but has a very

small cranal capacity (410 cc) and a more developed masticatory apparatus.

Like A. afarensis , A. aethiopicus has a flattened cranial

base and large anterior tooth sockets. A. aethiopicus was shown

to be the possible base of the boisei lineage; more primitive than robustus

yet not ancestral to it. There is, however, much debate about this.

Aethiopicus

P. robustus

P. robustus was first discovered

by Dr. Robert Broom in South Africa in 1938. Generally, P. robustus

has been found in three  different locations: Swartkrans, Dreimulen, and Kromdraai. P.

robustus is believed to have lived from 2.0 – 1.0 million years ago.

The species has a significantly larger cranial capacity than A. africanus

, and is more similar to a modern brain. In addition, P. robustus

has better developed muscle markings, more prominent tori, and thicker buttressing

structures than A. africanus. P. robustus also had a

substantially bigger postcanine tooth size in comparison to A. africanus

, indicating that robustus was not an herbivore that subsisted on hard gritty

nuts and plants, but rather an omnivore. The most vigorous debate surrounding

P. robustus has been whether or not it is a different species than

P. boisei or simply a geographic species of a wide-ranging variable population.

Most experts seem to agree that P. robustus and P. boisei have

separate lineages that follow similar evolutionary trends.

different locations: Swartkrans, Dreimulen, and Kromdraai. P.

robustus is believed to have lived from 2.0 – 1.0 million years ago.

The species has a significantly larger cranial capacity than A. africanus

, and is more similar to a modern brain. In addition, P. robustus

has better developed muscle markings, more prominent tori, and thicker buttressing

structures than A. africanus. P. robustus also had a

substantially bigger postcanine tooth size in comparison to A. africanus

, indicating that robustus was not an herbivore that subsisted on hard gritty

nuts and plants, but rather an omnivore. The most vigorous debate surrounding

P. robustus has been whether or not it is a different species than

P. boisei or simply a geographic species of a wide-ranging variable population.

Most experts seem to agree that P. robustus and P. boisei have

separate lineages that follow similar evolutionary trends.

Robustus

Smithsonian

Paranthropus boisei was first discovered by Mary Leaky in 1959, and

was first termed Zinjanthropus boisei or Zinj. The oldest

Paranthropus boisei was found at Omo, Ethiopia and dates to approximately

2.3 million years ago, while the youngest was found at Olduvai Gorge, and

dates to approximately 1.2 million years ago. P. boisei is best

known for its enormous postcanines, and seems to be the end point of a lineage

that was adapted to high masticatory stress needed to deal with hard low-quality

foods. One theory is that P. boisei died out because of overspecialization

to a specific environment, which prohibited it from adapting to a rapidly

changing environment and climate. Compared to other robust species,

P. boisei has a larger cranial capacity (500-550 cc), a more vertically

set face, and a sagittal crest on the mid-brain case, as opposed to the posterior.

It is widely accepted that P. boisei’s ancestor is A. africanus

. The discovery of P. boisei was important because it disproved

Milford Wolpoff’s “Single Species Hypothesis" that was so popular in the

1960s. This hypothesis stated that every environmental niche could

only support one species. Following his logic, P. robustus

was thought to be made up of all males, while A. africanus was thought

to be made up of all females. Because P. boisei of both sexes

were found in the same site and were dated to the same time, the discovery

proved that even if the South African material was a single sexually dimorphic

species, P. boisei was a different species contemporary with it,

bringing into doubt the validity of the single species hypothesis.

Paranthropus boisei was first discovered by Mary Leaky in 1959, and

was first termed Zinjanthropus boisei or Zinj. The oldest

Paranthropus boisei was found at Omo, Ethiopia and dates to approximately

2.3 million years ago, while the youngest was found at Olduvai Gorge, and

dates to approximately 1.2 million years ago. P. boisei is best

known for its enormous postcanines, and seems to be the end point of a lineage

that was adapted to high masticatory stress needed to deal with hard low-quality

foods. One theory is that P. boisei died out because of overspecialization

to a specific environment, which prohibited it from adapting to a rapidly

changing environment and climate. Compared to other robust species,

P. boisei has a larger cranial capacity (500-550 cc), a more vertically

set face, and a sagittal crest on the mid-brain case, as opposed to the posterior.

It is widely accepted that P. boisei’s ancestor is A. africanus

. The discovery of P. boisei was important because it disproved

Milford Wolpoff’s “Single Species Hypothesis" that was so popular in the

1960s. This hypothesis stated that every environmental niche could

only support one species. Following his logic, P. robustus

was thought to be made up of all males, while A. africanus was thought

to be made up of all females. Because P. boisei of both sexes

were found in the same site and were dated to the same time, the discovery

proved that even if the South African material was a single sexually dimorphic

species, P. boisei was a different species contemporary with it,

bringing into doubt the validity of the single species hypothesis.

Because of a lack of archaelogical evidence, there is very little known

about Paranthropus aethiopicus. However, it is generally accepted

that P. aethiopicus falls somewhere between the “robust” and “gracile”

australopithecines. The first specimen of P. aethiopicus was found

by a French expedition led by Camille Arambourg and Yves Coppens in southern

Ethiopia in 1967. P. aethiopicus was named a new species partly

because of its V-shaped jaw, which was different from other robust australopithecus

known to have lived in the area. The most famous specimen of P.

aethiopicus was discovered west of Lake Turkana and was dated to 2.5

million years old. It was known as “Black Skull” because mineral uptake

during fossilization gave the specimen a blue-black color. The “Black

Skull” specimen is similar to a male A. afarensis, but has a very

small cranal capacity (410 cc) and a more developed masticatory apparatus.

Like A. afarensis , A. aethiopicus has a flattened cranial

base and large anterior tooth sockets. A. aethiopicus was shown

to be the possible base of the boisei lineage; more primitive than robustus

yet not ancestral to it. There is, however, much debate about this.

Because of a lack of archaelogical evidence, there is very little known

about Paranthropus aethiopicus. However, it is generally accepted

that P. aethiopicus falls somewhere between the “robust” and “gracile”

australopithecines. The first specimen of P. aethiopicus was found

by a French expedition led by Camille Arambourg and Yves Coppens in southern

Ethiopia in 1967. P. aethiopicus was named a new species partly

because of its V-shaped jaw, which was different from other robust australopithecus

known to have lived in the area. The most famous specimen of P.

aethiopicus was discovered west of Lake Turkana and was dated to 2.5

million years old. It was known as “Black Skull” because mineral uptake

during fossilization gave the specimen a blue-black color. The “Black

Skull” specimen is similar to a male A. afarensis, but has a very

small cranal capacity (410 cc) and a more developed masticatory apparatus.

Like A. afarensis , A. aethiopicus has a flattened cranial

base and large anterior tooth sockets. A. aethiopicus was shown

to be the possible base of the boisei lineage; more primitive than robustus

yet not ancestral to it. There is, however, much debate about this.

different locations: Swartkrans, Dreimulen, and Kromdraai. P.

robustus is believed to have lived from 2.0 – 1.0 million years ago.

The species has a significantly larger cranial capacity than A. africanus

, and is more similar to a modern brain. In addition, P. robustus

has better developed muscle markings, more prominent tori, and thicker buttressing

structures than A. africanus. P. robustus also had a

substantially bigger postcanine tooth size in comparison to A. africanus

, indicating that robustus was not an herbivore that subsisted on hard gritty

nuts and plants, but rather an omnivore. The most vigorous debate surrounding

P. robustus has been whether or not it is a different species than

P. boisei or simply a geographic species of a wide-ranging variable population.

Most experts seem to agree that P. robustus and P. boisei have

separate lineages that follow similar evolutionary trends.

different locations: Swartkrans, Dreimulen, and Kromdraai. P.

robustus is believed to have lived from 2.0 – 1.0 million years ago.

The species has a significantly larger cranial capacity than A. africanus

, and is more similar to a modern brain. In addition, P. robustus

has better developed muscle markings, more prominent tori, and thicker buttressing

structures than A. africanus. P. robustus also had a

substantially bigger postcanine tooth size in comparison to A. africanus

, indicating that robustus was not an herbivore that subsisted on hard gritty

nuts and plants, but rather an omnivore. The most vigorous debate surrounding

P. robustus has been whether or not it is a different species than

P. boisei or simply a geographic species of a wide-ranging variable population.

Most experts seem to agree that P. robustus and P. boisei have

separate lineages that follow similar evolutionary trends.