Scientific Name: Alliaria petiolata

Classification:

Division: MagnoliophytaIdentification: Garlic mustard grows to be 2-3 ft tall. It has many white flowers of 4 petals on the end of 1-2 flowering stems. The leaves of the herb are alternate, triangular shaped, coarsely toothed, and 2-3 inches across. The fruits are black, cylindrical, and grooved. They ripen between mid-June and late September. Garlic mustard has a two year life cycle. It spends its first year as a green rosette 2-4 inches off the ground. It remains green through the winter. The second year garlic mustard will start to flower. Once dead, garlic mustard can be identified by erect stalks of dry, pale, brown seed pods that remain, and may hold a viable seed throughout the summer.

Class: Magnoliopsida

Order: Capparales

Family: Brassicaceae

There are several native plants that are similar in appearance to the garlic mustard. These include: toothworts (Dentaria), sweet cicely (Osmorthiza claytonii), and early sexifrage (Saxifraga virginica). The garlic mustard can be distinguished from these plants by the garlic/onion smell that the leaves, and stem emit when crushed.

Original Distribution: Garlic mustard was originally found in Northeastern Europe, from England east to Czechoslovakia and from Sweden and Germany south to Italy.

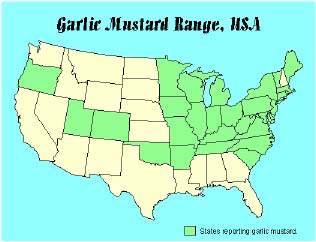

Current Distribution: At the present time garlic mustard is distributed throughout the northeastern and midwestern United States. It is found in 30 eastern/midwestern states, as well as 3 canadian provinces. It is found from Canada to South Carolina and west to Kansas, North Dakota, and as far as Colorado and Utah.

Garlic mustard is also found in North Africa, India, Sri Lanka, and New Zealand.

Site and Date of Introduction: The first sighting of the garlic mustard herb in the U.S.A. was in 1868 in Long Island, New York.

Mode of Introduction: Garlic mustard was intentionally introduced into the northeastern United States for food, erosion control, and medicine. Early European settlers brought the herb over to use as a garlic flavored herb with a good source of vitamin A and C. The herbs medicinal purposes include being used to treat gangrene and ulcers. The herb was also planted as a form of erosion control.

Reasons Why it has Become Established: The success of garlic mustard as an invasive species seems to be related to: the absence of natural enemies in North America, it's ability to self fertilize, high production of 15,000 seeds annually, rapid growth during the second growing season, and the release of phytotoxins from its root tissue.

In Europe, the original range of garlic mustard, there are over 30 insects that attack its leaves, stem, and seeds. There are also specialist herbivores that use garlic mustard as a food source. In North America there are no such enemies. A common herbivore found in northeasern U.S.A and southern Canada, the white-tailed deer prefers to eat native plants. The white-tailed deer thus facilitates the spread of garlic mustard by clearing out competitors, while at the same time spreading the seeds on its fur and exposing soil and seedbed by trampling.

The herb has a autogamous breeding system which produces 15,000 seeds annually, allowing for a small number of individuals to create large populations. These seeds remain viable for up to 5 years. After a dormant season, garlic mustard has a rapid growth period in the late fall to early spring, when most of the native plants are dormant. This allows the plant to dominate nutrients, space, and light when other plants cannot get to it.

Several phytotoxins were isolated from the tissue of garlic mustard. These phytotoxins may inhibit the growth of other plants and allow the garlic mustard to be invasive.

Garlic mustard may also reduce the competitive ability of native plants by interfering with the formation of mycorrihizal associations and root growth.

Ecological Role: In Europe, the original range of the garlic mustard, some herbivores relied on the plant for food.

Benefits: Garlic mustard has uses as a medicine for treatment if gangrene, and ulcers. It can also be used as garlic flavored herb with vitamin A and C. Additionally, garlic mustard can be planted for erosion control.

Threats: Garlic mustard is currently displacing native understory species in the forests of northeastern America and southern Canada. Native wildflowers include spring beauty, wild ginger, bloodrot, Dutchman's breeches, hepatica, toothwortsm, and trilliums. It displaces native herbaceous species within 10 years of establishment. Garlic mustard can invade undisturbed areas as well as disturbed areas.

Garlic mustard is also a threat to species that depend on the native understory species. For example, the endangered Virginia white butterfly (Pieris virginiensis) uses toothworts as a food supply during the caterpillar stage. Garlic mustard displaces toothworts, and is toxic to the eggs of the butterfly. Similarly, the native American butterfly (Pieris napi aleracea) which commonly use native mustards as their host plants, tries to use garlic mustard, but their larvae die.

Control Level Diagnosis: Highest Priority- Garlic mustard has spread far from the original place of introduction in Long Island. It has proven to be a highly invasive plant with characteristics that allow it to contine to be invasive. If left alone, garlic mustard will continue to displace forest understory plants across the United Stated in both disturbed and undisturbed forests.

Control Method: There are many methods currently used to try and remove garlic mustard. These include mechanical controls, chemical controls, and biological controls.

Mechanical control: Garlic mustard can be pulled out by hand at or before the onset of flowering. The whole root must be removed because new plants can sprout from root fragments. After pulling, the soil must be thoroughly tamped to prevent soil disturbance, and bringing up seeds from the seed bank.

Cutting the plant is a less destructive control. The flower stalk can be cut at ground level or within several inches from the ground, only once the flowering begins. Cutting too soon may cause resprouting, and cutting too high may cause the plant to produce additional flowers.

If too large an area is infested for pulling or cutting to be effective, fall or early spring burning is an option. Spring burns must take place early, so they do not cause harm to wild flowers. 3-5 years of fires are needed, and should be supplemented by hand pulling or cutting afterward. Fire may enhance the spread by surviving seedlings by exposing bare soil. A study done in 2000 shows that repeated burning may actually increase the number of flowering stems.

Chemical control: 1-2% active ingredient solution of glyphosoate can be applied to the foliage of individual plants, and dense patches during late fall or early spring when most native plants are dormant. The temperature should be above 50 degrees F, with no rain expected for 8 hours. Glyphosate is a non selective herbicide that will kill non target plants. DIRECTIONS AND WARNINGS SHOULD BE READ CAREFULLY BEFORE USING ANY CHEMICAL CONTROL.

Biological control: Research towards biological control are currently taking place at Cornell University.

References:

Anderson, R.C. et al. 1996.

Aspects

of an Invasive Plant, Garlic Mustard, in Central Illinois. 4(2): 181-191

Luken, J.O., and M. Shea. 2000. Repeated Prescribed Burning at Dinsmore Woods State Nature Preserve (Kentucky, USA): Responses of the Understory Community. Natural Areas Journal. 20(2): 150-158

Renwick, J.A.A. et al., 2001. Dual Chemical Barriers Protect a Plant Against Different Larval Stages of an Insect. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 27(8): 1575-1583

Roberts, K.J., and R.C. Anderson. 2001. Effect of Garlic Mustard Extracts on Plants and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal (AM) Fungi. American Midland Naturalist. 146(1): 146-152

Vaughn, S.F., and M.A. Berhow. 1999. Allelochemicals Isolated from Tissue of the Invasive Weed Garlic Mustard. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 25(11): 2495-2504

Cipollini, D. October 2001 (10/9/01). Cipollini Lab Page. http://www.wright.edu/~don.cipollini/

Rowe, P., and J. Swearingen. 2/6/01 (9/26/01). Garlic Mustard. http://www.nps.gov/plants/alien/fact/alpe1.htm

The Nature Conservancy. June 2000 (9/26/01) Wildland Invasive Species Program. http://tncweeds.ucdavis.edu/alert/alrtalli.html

United States Department of Agriculture. July 1999 (9/26/01). Pest Alert. http://www.fs.fed.us/na/morgantown/fhp/palerts/garlic/garlic.htm

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. 4/30/99 (9/26/01). Controling Garlic Mustard. http://www.dnr.state.wi.us/org/land/er/invasive/factsheets/garlic.htm