Common Name: Northern Snakehead (also Amur snakehead or eastern snakehead)

Scientific Name: Channa argus

Classification:

Phylum: Chordata

Superclass: Osteichthyes

Class: Actinopterygii

Subclass: Neopterygii

Infraclass: Teleostei

Superorder: Acanthopterygii

Order: Perciformes

Suborder: Channoidei

Family: Channidae

Genus: Channa

Species argus (Cantor, 1842)

Identification:

Colored dark brown with

black spots, C. argus has a long, rounded body that is thick in

the mid-section and tapers off towards the tail fin. Adults have long

dorsal and anal fins, a small head, and large mouth with bands of

smaller, finger-like teeth lining the upper jaw and large canine-like

teeth protruding from their lower jaw. The snakehead takes its common

name from the enlarged scales on the top of its head and its

forward-shifted eyes, giving the fish a facial configuration that

appears “snake-like.” Adults can grow up to 4 feet long and weigh up to

15 pounds (Courtenay and Williams, 2004; ISSG, 2004).

Colored dark brown with

black spots, C. argus has a long, rounded body that is thick in

the mid-section and tapers off towards the tail fin. Adults have long

dorsal and anal fins, a small head, and large mouth with bands of

smaller, finger-like teeth lining the upper jaw and large canine-like

teeth protruding from their lower jaw. The snakehead takes its common

name from the enlarged scales on the top of its head and its

forward-shifted eyes, giving the fish a facial configuration that

appears “snake-like.” Adults can grow up to 4 feet long and weigh up to

15 pounds (Courtenay and Williams, 2004; ISSG, 2004).

Original Distribution: Native species range for C. argus includes the Amur River basin and Songhua River, Manchuria; rivers of China and upper tributaries Yangtze River basin in northeastern Yunnan Province (Evermann and Shaw, 1927); and throughout Korea, with the exception of in northeastern portion of the country (Okada, 1960; Berg, 1965; Kimura, 1934; Nichols, 1943; Mori, 1952; Xinluo and Yinrui, 1990; Ruihua, 1994).

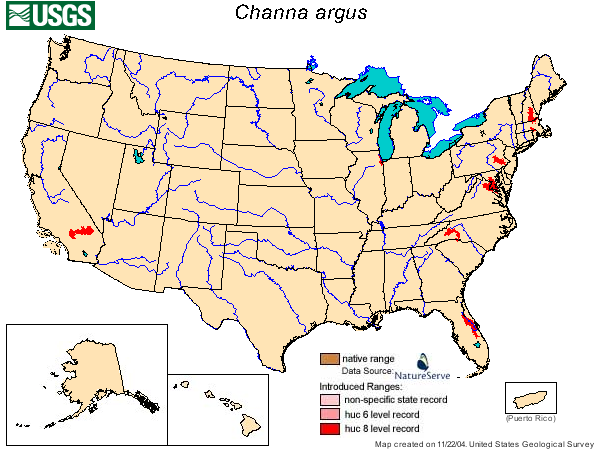

Current Distribution: The current geographic distribution of C. argus includes (in addition to the native distribution): Eastern Europe (Czechoslovakia); Republic of the Russian Federation in the Tunguska River at Khabarovsk, Ussuri River basin, and Lake Khanka (Herzenstein and Warpachowski,1887; Berg, 1965; Popova, 2002); Japan; Kazakhstan; Turkmenistan (Aral Sea basin); United States; and Uzbekistan. Within the United States, C. argus has been found in eight different states (ISSG, 2004; see table below).

Site and Date of U.S. Introduction: According to the USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database (USGS, 2004), C. argus was first collected in 1997 at Silverwood Lake in San Bernardino, CA, though this capture was unconfirmed because the specimen was discarded and no photograph was kept on file (Courtenay and Williams, 2004). In 2000, two specimens were collected from the St. John’s River in Florida, yet attempts of collect additional C. argus specimens from the location since 2001 have been unsuccessful. The first established population of C. argus was collected from a retention pond behind a shopping mall near Crofton, MD. The original breeding pair was traced by investigators with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources to one specific intentional release (Maryland Department of Natural Resources, 2002).

Chronology of United States Introduction and Spread:

| State | County | Locality | Year | Status |

| CA | San Bernardino | Silverwood Lake | 1997 | collected |

| FL | Seminole | St. Johns River | 2000 | collected |

| IL | Cook | Lake Michigan | 2004 | collected |

| MA | Worcester | Newton Pond | 2001 | collected |

| MA | Middlesex | Massapoag Pond | 2004 | collected |

| MD | Anne Arundel | Pond in Crofton | 2002 | established |

| MD | Anne Arundel | Pond in Crofton | 2002 | eradicated |

| MD | Charles | Potomac River | 2004 | collected |

| MD | Charles | Pomonkey Creek | 2004 | collected |

| MD | Charles | Mattawoman Creek | 2004 | collected |

| MD | Montgomery | Pine Lake | 2004 | collected |

| NC | Gaston | Lake Wylie | 2002 | collected |

| PA | Philadelphia | Edgewood Lake | 2004 | collected |

| PA | Philadelphia | Edgewood Lake | 2004 | established |

| VA | Fairfax | Potomac River | 2004 | collected |

| VA | Fairfax | Mulligan Pond | 2004 | collected |

| VA | Fairfax | Dogue Creek | 2004 | collected |

| VA | Fairfax | Mason Neck | 2004 | collected |

| VA | Fairfax | Dogue Creek | 2004 | collected |

| VA | Fairfax | Dogue Creek | 2004 | established |

| VA | Fairfax | Kane Creek | 2004 | collected |

|

Source: USGS, 2004. |

||||

Mode(s) of Introduction: C. argus was introduced through intentional release by Asian food importers to establish harvestable stocks of the snakehead to supplement/reduce foreign import of the highly desired food product (Harris, 2002). C. argus has also been introduced through release of pet snakeheads, as was the case in of the Crofton, MD breeding pair in 2002. As reported in the Washington Post, a local man had originally ordered the pair of live snakeheads from a Chinatown market in New York to prepare a traditional soup remedy for his ill sister; however, his sister had recovered by the time the order arrived and the man released the fish into the pond near Crofton and after they had outgrown their aquarium (Huslin, 2002).

Reason(s) Why it has Become Established: The Northern Snakehead is highly adaptable to variable environmental conditions with latitudinal and climatic ranges greater than that of other snakehead species. Prior to Federal regulations restricting importation of the species, the Northern Snakehead was the most widely available snakehead sold as a live-food fish in the U.S. accounting for the largest volume and greatest weight of live snakeheads imported into the U.S. until 2001 (Courtenay and Williams, 2004). Additional investigation by Courtenay and Williams (2004) showed that despite the fact that fourteen states banned possession of live snakeheads prior to August 2002 the authors were able to procure live specimens from various cities around the U.S. The authors also reported several raids by several state Fish and Wildlife agents producing large numbers of illegal live Northern snakeheads smuggled into Asian markets.

Ecological Role: Though little is known about specific ecological impacts do to their recent introduction, as previously gauged from past Northern snakehead invasions outside of the United States. The species has the potential to wipe out a small pond and stream ecosystem, moving from failed ecosystem to failed ecosystem as the available prey becomes exhausted in the area as noted when the Northern Snakehead was introduced into the Syr Dar’ya, river in Uzbekistan. C. argus fed on 17 species of resident fishes (juveniles through adults), including prey up to 33 percent of the predator’s body length (Dukravets and Machulin, 1978).

In addition to other fish, the Northern Snakehead’s carnivorous diet includes crayfish, dragonfly larvae, beetles, and frogs giving it the ability to consume large percentages of indigenous animal biomass, thereby potentially depleting many different key sectors of these relatively small aquatic ecosystems.

The Northern snakehead also has high reproduction rates with adults producing between 1,300 and 15,000 eggs per spawn at a frequency of 1-5 spawns per year (ISSG, 2004). Snakeheads can breathe air, surviving up to four days on land as long as their skin remains moist and has the ability to survive colder or dry temperatures by burrowing into the mud (Hilton, 2002).

Benefit(s): Snakehead species are important to the fishing industry in Asia and have been shown to become commercially fishable in areas of past introduction (Berg, 1965; Baltz, 1991; Dukravets, 1992; FAO, 1994). In China and neighboring Asian countries there is a large yearly demand for Northern Snakehead as a major food ingredient and a folk remedy with supposed medicinal properties. According to a recent Associated Press article, Singapore alone imports more than 1,200 tons of northern snakehead a year (Harris, 2002).

Threat(s): C. argus is a rapacious primary predator consuming a wide variety of prey besides other fish whose predacious nature, lack of natural predators, high fertility, and adaptability to a wide range of environmental conditions qualify it as a potentially dangerous invader in climatologically-favorable and resource-rich U.S. ponds, lakes, and streams (Courtenay and Williams, 2004; ISSG, 2004; Okada, 1960). Also, given that C.argus has a geographic range of native range (24-53º N) and temperature tolerance (0-30 ºC) and was established in Maryland in 2002 and possibly in Florida around the same time, the probability that the C. argus will become more widely established is quite favorable (Courtenay and Williams, 2004).

Effective October 4, 2002, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service issued a final rule through the Federal Register adding all species of snakehead fishes in the Channidae family to the list of injurious fish, mollusks, and crustaceans (Fed. Reg., 2002). This rule stated that the snakehead has an “aggressive, predatory nature” and that the species as a whole have the potential to “threaten the wildlife and wildlife resources of the United States.”

Control

Level Diagnosis: Medium

Priority-

Spread of

the Northern Snakehead should be addressed soon, as the range of

collected species is geographically increasing and the ecological

impacts are still unclear. The Northern Snakehead has been recently

detected as far north as the Great Lakes, albeit in small numbers.

Also, thought it is believed that the C. argus is not as well

equipped for long overland travel except during its juvenile stage due

to the comparatively rounded body of the adult Argus (species with

flattened ventral surfaces are more stable), the Northern Snakehead has

the ability nonetheless to disperse to new, crowded environments during

or directly after heavy rains (Liem, 1987).

The identification of the species so far north from the main area of interest in the Mid-Atlantic States shows that the species has the ability to widely spread, and even accounting for the generally poor nature of detection, the species is not yet over-running ecosystems.

The Snakehead’s menacing appearance is at least partially responsible for its earned reputation of ill-repute. Most of the media hype centered on the “poor personality” of the snakehead disregards the true extent and viability of the snakeheads’ invasion. Common sense measures instituted at the Federal and State levels through Federal Wildlife Service (FWS) and the state departments of conservation should be sufficient to stem the tide of this invader. These policies, coupled with large fines for known violations of Federal statues regarding the release of the Northern Snakehead by Asian food importers to encourage local breeding stocks, seem adequate to largely contain the runaway invasion of the Northern Snakehead throughout the United States.

Control Method: The Virginia State government signed House Bill 2752 or the Nonindigenous Aquatic Nuisance Species Act, which identifies several species including the snakehead as a Nonindigenous aquatic nuisance species and gives the Board of Game and Inland Fisheries the authority to declare other species as aquatic nuisance species. The bill makes it illegal to possess, import, sell, give, receive, transport or introduce these animals, but provides for permits for legitimate research. The bill was signed by the Governor Mark Warner on March 16, 2003 (http://leg1.state.va.us/cgi-bin/legp504.exe?031+ful+HB2752ER).

The Maryland Secretary of Natural Resources also instituted a Snakehead Scientific Advisory Panel in July 26, 2002 to “deliver to the Secretary a report that assesses the risks to Maryland’s natural resources posed by the northern snakehead fish; evaluates the options for its control or eradication in and around the pond where it was found, including the probability of success and attendant environmental consequences; and recommends by consensus a preferred course of action to be executed by the Department.” (http://www.dnr.state.md.us/irc/ssap.pdf)

References:

Baltz, D.M. (1991)

Introduced fishes in marine systems and inland seas: Biological

Conservation, v. 56, p. 151-177.

Berg, L.S. (1965) Freshwater fishes of the USSR and adjacent countries, Vol. III (4th ed., improved and augmented): [Translated from Russian; original 1949, Jerusalem, Israel Program for Scientific Translations], p. 937-1381.

Cantor, T.E. (1842) Ophicephalus argus: General features of Chusan with remarks on the fauna and flora of that Island. Annals and Magazine of Natural History. Volume IX: p.484.

Courtenay, Jr., W.R. and James D. Williams. (2004) Snakeheads (Pisces, Channidae): A Biological Synopsis and Risk Assessment. U.S. Geological Survey circular; 1251.

Dukravets, G.M., and Machulin, A.I., 1978, The morphology and ecology of the Amur snakehead, Ophiocephalus argus warpachowskii, acclimatized in the Syr Dar’ya basin: Journal of Ichthyology, v. 18, no. 2, p. 203-208.

Dukravets, G.M. (1992) The Amur snakehead, Channa argus warpachowskii, in the Talas and Chu River drainages: Journal of Ichthyology, v. 31, no. 5, p. 147-151.

Evermann, B.W.,, and Shaw, T., 1927, Fishes from eastern China, with descriptions of new species: Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences, v. 16, p. 97-122.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). (1994) Aquaculture production 1986-1992 (4th ed.): Rome, Italy, FAO Fisheries Circular 815, 216 p.

Fuller, Pam. (2004) Channa argus. Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL. http://canal.er.usgs.gov/queries/SpFactSheet.asp?speciesID=2265; Revision Date: 7/23/04.

Harris, Edward. “Horror to some, lunch to others: Snakehead fish considered tasty in Singapore,” The Associated Press, July 29, 2002, Pg. C13.

Herzenstein, S., and Warpachowski, N., 1887, Notizen über die fischfauna des Amur-Bekensund der angrenzenden gebiete: Transactions of the St. Petersburg Philosophical Society, Zoological Division, v. 18, p. 1-58.

Hilton, R., 2002. The Northern Snakehead: An Invasive Fish Species. Cambridge Scientific Abstracts.

Huslin, Anita. “Snakeheads' Luck Put Pond in the Soup.” The Washington Post. 12 July 2002; Page A1.

Kimura, S., 1934, Description of the fishes collected from the Yangtze-kiang, China, by the

late Dr. K. Kishinouye and his party in 1927-1929: Journal of the Shanghai Science Institute, v. 3, no. 1, p. 11-247.

ISSG Database. Solenopsis invicta profile; compiled by The State of Queensland, Department of Primary Industries; last mod. 24 September 2004; Available at http://www.issg.org/database/species/ecology.asp?si=380&fr=1&sts=sss

Liem, K.F., 1987, Functional design of the air ventilation apparatus and overland excursions ty teleosts: Fieldiana, Zoology, v. 37, p. 1-29.

Maryland Department of Natural Resources Press Release. “DNR Officials Identify Source of Snakehead Fish.” 11 July 2002. 20 November 2004 http://www.dnr.state.md.us/dnrnews/pressrelease2002/071102.html.

Mori, T., 1952, Check list of the fishes of Korea: Memoirs of the Hyogo University of Agriculture, v. 1, no. 3, p. 1-228.

Nichols, J.T., 1943, The fresh-water fishes of China, Vol. IX of Natural history of central Asia: New York, American Museum of Natural History, 322 p.

Okada, Y., 1960, Studies of the freshwater fishes of Japan, II, Special part: Prefectural University of Mie, Journal of the Faculty of Fisheries, v. 4, no. 3, p. 1-860, 61 plates.

Popova, O.A., 2002, Channa argus (Cantor, 1842), in Reshetnikov, Yu. S., ed., Vol. 2 of Atlas of Russian Freshwater Fishes: Nauka, Moscow, Russia, p. 141-144.

Ruihua, D., 1994, The fishes of Sichuan, China: Chengdu, Sichuan, China, Sichuan Publishing House of Science and Technology, 641 p.

“Injurious Wildlife Species; Snakeheads (family Channidae), Proposed Rule.” Federal Register 67 (October 4, 2002): 48855-48864.

USGS. 2004. Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL. http://nas.er.usgs.gov

Xinluo, Chu, and Chen Yinrui, 1990, The fishes of Yunnan, China, Part II, Cyprinidae: Beijing, China, Science Press, 313 p.