Introduced Species Summary Project

Russian Olive

(Elaeagnus angustifolia L.)

| Project Home | Taxonomy | Identification | Distribution | Introduction Facts | Establishment | Ecology | Benefits | Threats | Control |

Common Name: Russian olive (also Russian-olive, Russian olive); Oleaster

Scientific

Name: Elaeagnus angustifolia L.

Classification:

Division: Magnoliophyta (angiosperms,

flowering plants)

Class: Magnoliopsida

(dicotyledons)

Order: Rhamnales

Family: Elaeagnaceae

(Oleaster family)

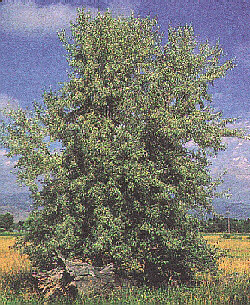

Identification: The

Russian olive is a large, spiny, perennial deciduous shrub or small growing

tree (up to 40ft.) that is usually found in riparian areas, as well as fields

and other open areas. The plant

has elliptical to lanceolate shaped leaves and thorny branches. The leaves are alternate and simple,

about 1 to 3 inches long and ½ inch wide, distinctly scaly on the top and

silvery and scaly on the bottom.

The leaves of the Russian olive are dull green to gray in color. Buds are quite small, round and

silvery-brown in color and covered with many scales. The branches are silvery, scaly and thorny when the plant is

young, and turn a shiny, light brown color when mature. The bark on the Russian olive is at

first smooth and gray, and then becomes unevenly rigid and wrinkled later on.

Its fruit is like a berry, about ½ inch long, and is yellow when young (turning

red when mature), dry and mealy, but sweet and edible. The fruit matures from August to

October and stays on the tree throughout the winter. In mid-summer, from May to June, the Russian olive blooms

fragrant yellow flowers with silvery-gray willow-like leaves, which can cause

it to be easily confused with the willow-leaf pear tree.

Original

Distribution: The Russian

olive is native of temperate western Asia (Afghanistan; Armenia; Azerbaijan;

China; Georgia; Iran; Kazakhstan; Mongolia; Russia; Tajikistan; Turkmenistan;

Uzbekistan); some parts of tropical Asia (northwestern India and northeastern

Pakistan); and southeastern Europe (Belarus; Moldova). The Russian olive was originally

planted in Eurasia as an ornamental tree, and was first cultivated in Germany

in 1736.

Original

Distribution: The Russian

olive is native of temperate western Asia (Afghanistan; Armenia; Azerbaijan;

China; Georgia; Iran; Kazakhstan; Mongolia; Russia; Tajikistan; Turkmenistan;

Uzbekistan); some parts of tropical Asia (northwestern India and northeastern

Pakistan); and southeastern Europe (Belarus; Moldova). The Russian olive was originally

planted in Eurasia as an ornamental tree, and was first cultivated in Germany

in 1736.

Site and Date of Introduction: The Russian olive was

introduced to the central and western United States in the late 1800’s as an

ornamental tree and a windbreak, before spreading into the wild. By the mid 1920’s it became naturalized

in Nevada and Utah, and in Colorado in the 1950’s.

Current Distribution: The Russian olive is found throughout North America,

but mainly in the central and western portions of the United States. After introduction it escaped

cultivation and naturalized in 17 western states from the Dakotas, Nebraska,

Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas westward to the Pacific coast. It is most abundant in the Great Basin

Desert region and the riparian zones of the Great Plains. The Russian olive is also found on the

east coast of the United States from Pennsylvania to Virginia, and in southern

Canada, from Ontario to British Columbia.

Mode(s) of Introduction: The

Russian olive was purposely introduced by human beings since it is an

attractive, thriving landscape species. Its dense, silvery foliage provides a good hedge or screen

to block out unwanted views. The

plant is quite hardy and grows well near highways in particular. In the 1940’s, the Russian olive was

deliberately planted in the eastern and southern U.S. for revegetation of

disturbed areas and until recently it was transplanted for wildlife planting

and windbreaks by the U.S. Soil Conservation Service.

Reason(s) why it has Become Established: The Russian olive has been extremely successful in the

United States mainly due to its resistance to varying water, soil and

temperature conditions, a proliferation of seed-dispersing birds and its

nitrogen-fixing ability. Birds

foraging on the Russian olive’s fruit scatter seeds at a very rapid rate. As the seeds are ingested along

with the fruit by birds and other small mammals, they are subsequently

scattered in their droppings. The

seeds of the Russian olive are very resilient, enduring the stomach’s digestive

juices, and distributing themselves for up to three years over a broad range of

soil types.

The Russian olive is simply a very adaptive tree and tends

to be an initial colonizer post-disturbance. It is very widespread in riparian zones and is found growing

along floodplains, riverbanks, streams and marshes. The Russian olive can tolerate large amounts of salinity and

can grow well in a variety of soil combinations from sand to heavy clay. It can also survive a unique range of

temperature (from –50 to 115 degrees Fahrenheit) and can tolerate shade well,

allowing it to withstand competition from other trees and shrubs. The Russian olive can also absorb

nitrogen into its roots, thereby having the ability to grow on bare, mineral

surfaces and dominate other riparian vegetation where old growth trees once

survived.

Ecological

Role: The fruit of the Russian olive tree is a great source of

food and nutrients for birds, so while this suggests the plant plays an

important ecological role in birds’ habitat, ecologists have found that bird

species richness is actually greater in areas with a higher concentration of native

vegetation. Over 50 different

species of mammals and birds do eat the fruit, 12 of them being game

birds. Deer and other livestock

feast on the leaves of the Russian olive and beavers use the branches for

constructing dams. The canopy of

the Russian olive provides good thermal cover for some wildlife species. Doves, mocking birds, roadrunners and

other birds use the thick growth of branches as nesting sites.

Ecological

Role: The fruit of the Russian olive tree is a great source of

food and nutrients for birds, so while this suggests the plant plays an

important ecological role in birds’ habitat, ecologists have found that bird

species richness is actually greater in areas with a higher concentration of native

vegetation. Over 50 different

species of mammals and birds do eat the fruit, 12 of them being game

birds. Deer and other livestock

feast on the leaves of the Russian olive and beavers use the branches for

constructing dams. The canopy of

the Russian olive provides good thermal cover for some wildlife species. Doves, mocking birds, roadrunners and

other birds use the thick growth of branches as nesting sites.

Benefit(s): The Russian olive is principally

an ornamental. Including the

ecological benefits listed above, the Russian olive and its tremendous

adaptability has allowed it to be planted for erosion control and highway and landscape

enhancement. The branches from the

Russian olive not only provide shade and shelter, but some fuel wood, gum and

resin. The fruit of the Russian

olive can be used as a base in some fruit beverages and the plant has also been

know to be a source of honey. As

previously mentioned, the Russian olives’ nitrogen-fixing ability makes it a

good companion tree by increasing surrounding crops’ yield and growth, however

with its ability to take over very quickly, it is wise to plant another

species.

The Russian olive, with its

tendency to spread quickly, is a menace to riparian woodlands, threatening

strong, native species like cottonwood and willow trees. They are responsible for out competing

a lot of native vegetation, interfering with natural plant succession and

nutrient cycling and choking irrigation canals and marshlands in the western United

States. This displacement of

native plant species and critical wildlife habitats has undoubtedly affected

native birds and other species.

The heavy, dense shade of the Russian olive is also responsible for

blocking out sunlight needed for other trees and plants in fields, open

woodlands and forest edges.

Overall, areas dominated by the Russian olive do not represent a high

concentration of wildlife.

Control Level Diagnosis: The

Russian olive has been categorized as a noxious weed in New Mexico and Utah,

and as an invasive weed by California, Nebraska, Wisconsin and Wyoming state

authorities. There is a serious

concern that should the Russian olive continue to establish itself, it will

become the dominant woody plant along Colorado’s rivers, where it is already

taking over hundreds of thousands of acres of cottonwood and willow

woodlands. Some cities are already

taking steps to remove the Russian olive.

Control Method: The Russian olive is difficult,

if not impossible, to control or eradicate. The main reason for this is the Russian olives’ capability

of producing root crown shoots and “suckers”. Pruning

or simply cutting does not have any effect on the Russian olive, as it tends to

resprout heartily from the root stump. The Russian olive is also a fire resistant plant and tends to

colonize burned areas, yet burning with a combination of herbicide spraying on

the stump can possibly prevent the Russian olive from resprouting. Mowing the Russian olive with a brush

type mower and removing cut material (and then spraying) is probably the most

effective way of attempting to eradicate the plant. There

are two kinds of fungus that can affect the Russian olive: Verticillium wilt and Phomopsis

canker. Verticillium wilt attacks

and usually kills the Russian olive in eastern areas that are very humid and

wet or poorly drained, causing the leaves to wilt. Canker disease is a reddish-brown to black canker that

appears on smaller branches, resulting in a kind of “bleeding” on the diseased

areas. Once the fungus covers the

branch, lack of water causes the leaves to wilt and the branches die off. Although the Russian olive can thrive

without water, it becomes stressed when there is a severe lack of water,

causing the fungus to appear.

Finally, few animals and insects feed or bother the Russian olive, so

there tends to be no effective biological control.

References:

1. Haber,

Erich. Russian-olive –

Oleaster. Elaeagnus angustifolia

L. Oleaster Family – Elaeagnaceae. Invasive Exotic Plants of Canada Fact Sheet

No. 14. National Botanical

Services, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

April 1999.

2. Muzika,

Rose-Marie, U.S. Forest Service, Morgantown, WV and Jil M. Swearingen, U.S.

National Park Service, Washington, DC. “Weeds Gone Wild” Plant Conservation

Alliance, Alien Plant Working Group. August 1997 http://www.nps.gov/plants/alien/fact/elan1.htm

3. National

Invasive Species Council. U.S.

Department of the Interior – South.

National Agricultural Library of the U.S. Department of

Agriculture. Washington, D.C. Dec.

19, 2001. http://www.invasivespecies.gov/profiles/russolive.shtml

4. USDA, ARS,

National Genetic Resources Program. Germplasm Resources Information Network -

(GRIN). [Online Database] National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville,

Maryland. http://www.ars-grin.gov/var/apache/cgi-bin/npgs/html/taxon.pl?14915

5.

USDA, NRCS. 2001. The PLANTS Database, Version 3.1

National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA. http://plants.usda.gov/cgi_bin/plant_profile.cgi?symbol=ELAN&photoID=elan_1v.jpg#links

6. U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station,

Fire Sciences Laboratory (2002, February). Fire Effects Information

System. http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/elaang/index.html

Author: Emily Collins

Last Edited: March 6, 2002

| Project Home |

Project Editor: James A. Danoff-Burg, Columbia University