Scientific Name: Linepithema humile

Classification:

Class: Insecta

Order: Hymenoptera

Family: Formicidae

Subfamily: Dolichoderinae

Identification:

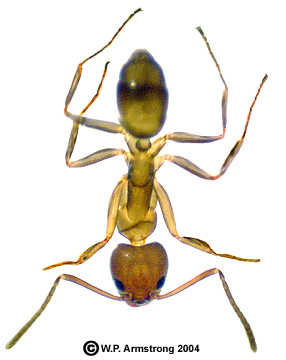

The wingless worker ant is 2-3 mm long and light to dark

brown. The queen and males are slightly larger and

darker.

There are a

variety of detailed characteristics that

differentiate the Argentine ant from other species.

- Five to eight large teeth line the mandibles.

- The eyes are below the widest point of the head.

- The antennae are divided into twelve segments, with the first segment being equal to the length of the head.

- One node separates the hind body segments.

- The body surface of the ant is smooth and lacks hair on the dorsum of the head and thorax.

- The ant has no sting.

- Argentine ants trails are often at least five ants wide, and they can be seen traveling up trees and buildings in search of food.

- When crushed, the arthropod gives off a musty smell (versus the acidic smell most ants have).

Original

Distribution:

The Argentine ant is native to Northern Argentina, Southern Brazil,

Uruguay, and Paraguay. Most samples of the introduced ranges in

the Southeastern United States and California are genetically related

to

populations from the Southern Rio Parana in Argentina.

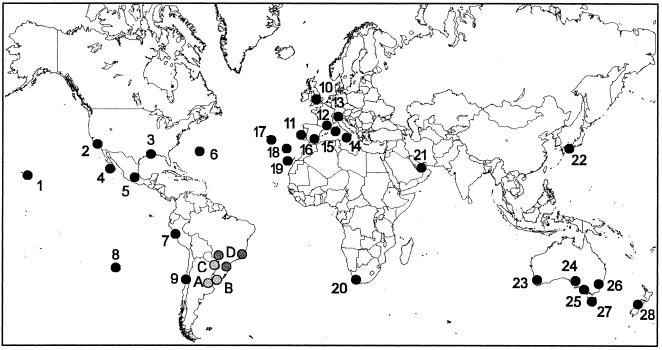

Current

Distribution:

L. humile was accidentally introduced in all locations where it has

invaded. The ant is found on all continents except Antarctica, as

well as on many oceanic islands. It has invasive

populations in

Australia, Bermuda, Chile, Cuba, France, Italy, Japan, Mexico, New

Zealand, Peru, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, United Arab

Emirates, and the United States. Argentine ants in the

continental United States occupy locations from California to the

Southeastern States. In Hawaii, L. humile has populations on Maui

and the Big Island.

Site

and Date of Introduction:

United States - The ant

was first

recorded in the United States by E. Foster in 1891. L. humile is

believed to have entered the United

States in

New Orleans around the early 1890's. It was first sighted in

California in 1907. The species probably entered Hawaii in the

1940's.

The list includes:

- Australia (1939)

- Bermuda (1949)

- Chile (1910)

- Cuba (1995)

- France (1905)

- Italy (1926)

- Japan (1993)

- Mexico (1946)

- New Zealand (1990)

- Peru (1974)

- Portugal (1900)

- South Africa (1901)

- Spain (1923)

- Switzerland (1980)

- United Arab Emirates (1995)

Mode(s) of

Introduction:

The primary mode of introduction is probably

shipping. It is believed the ant came to Louisiana through

Argentine

shipments of coffee or sugar. It spread across the southern

states, most likely by train, and eventually moved into

California. The ant was probably introduced to Hawaii by way of

goods shipped from California.

Reason(s)

Why it has Become Established:

Argentine ants are able to establish new

colonies with as little as ten worker ants and one queen.

Introduced populations differ from native

populations. In their native habitat, genetically

diverse territorial colonies fight for resources. In

introduced habitat, genetic similarity has led to

"supercolonies". In these population structures the ants do not

fight with each other, but rather

spend their time and energy foraging and out competing native ants for

food and habitat. L. humile colonies exhibit higher

densities than do colonies of species native to the U.S.

Introduced

colonies are polygynous, meaning they have more than one

reproductive queen within a colony. Polygyny allows them higher

rates of reproduction and allows the "extra" queens to branch off

with worker ants to establish additional nests. Introduced

populations form new colonies by budding (wingless queens and workers

travel

on the ground

to a form a new nest) and jumping (movement by human transport).

In native colonies, queens and males fly

to a new site, which

enhances genetic diversity (and thus, intraspecific competition).

The Argentine ant is omnivorous, although it mainly feeds on the

honeydew

produced by

smaller insects like aphids. A general diet has allowed the ant

to survive in a variety of habitats. They prefer areas that are

moist

year round, and are often found under logs, rocks, or refuse.

They are often found around humans due to their affinity for moist

conditions.

Ecological

Role:

L. humile is an extremely competitive species of "tramp"

ant that often

displaces native species when introduced. Invasive colonies have

a very high density that allows them to out compete native

species. Queens may lay up to 60 eggs a day. Since there

can be many queens in a nest, reproduction is

prolific. L. humile may survive in tropical to temperate

climates. It prefers moist habitat and is found near people in

dry habitats, such as Southern California. Cold temperatures and

aridity limit its range.

Benefit(s):

L. humile has had mostly negative effects on invaded ecosystems.

However, it has been suggested as a biological control

agent in the spread of the pine processionary moth (Thaumetoppoea

pityocampa) in Portugal. Ants in general perform a variety of

important roles in ecosystems, such as

aerating the soil, breaking down organics, and protecting aphids that

provide them with food.

Threat(s):

L. humile is a threat on many levels to native ecosystems. It

out competes many native ants for food and habitat. It has been

negatively associated with arthropod diversity in the areas it has

invaded. In

Southern California the ant has replaced harvester ants in many

areas. Animals higher up the food chain that prey on native ants

may be negatively affected by the presence of L. humile. Recent

studies have suggested that decreasing numbers of coast horned lizards

(Phrynosoma coronatum) and shrews (Notiosorex crawfordi) are related to

the

presence of L. humile. The ants may also feed on the eggs

of native amphibians, reptiles, and birds. Native plants that

depend on native ants for seed dispersal are negatively affected by the

presence of L. humile. Argentine ants can also cause direct and

indirect damage to crops. In South Africa they prey upon bees and

steal honey. They feed on the fruits and buds of different

plants, such as citrus trees. They cause indirect damage by

protecting smaller insects, such as aphids, that may feed on

crops. Argentine ants are considered a major pest to people in

areas they have invaded.

Control

Level Diagnosis:

L. humile should be actively controlled and eliminated in areas it has

recently invaded. Since the ant is capable of a high level of

damage, eliminating introduced

populations in new areas should be given the "Highest Priority".

L. humile invasion can result in large economic and ecologic

costs. Based on studies from previous invaded habitats, it has

been shown that the ant can cause decline of arthropod

diversity, local extinction, decline of animals higher up in the

food chain, decline in native plant species, and significant direct

and indirect damage to crops. L. humile is commonly found

in and around human structures. Increased human presence may

increase populations and spread of argentine ants by providing

increased moisture due to runoff and by offering additional

opportunities for jump dispersal. As L. humile establishes itself

and

spreads it is harder to control.

L. humile has benefited from genetic similarity, rather than diversity, in its introduced range. Genetic similarity has allowed the ant to build supercolonies, and to focus on interspecies conflict. It is possible that a lack of genetic diversity may leave the ant susceptible to parasites or disease. It would be shortsighted to wait for this to happen. The best way to control the Argentine ant is to inspect cargo and garbage for its presence. The ant has proven itself able to survive long journeys, and can travel in food products, garbage, potted plants, soil, and almost all types of cargo. Control becomes expensive and diffifcult after the ant becomes invasive. Many different methods have been applied to try and eradicate the species. In California citrus groves, many remedies were tried, including tar bands around tree trunks, arsenic syrup, and chlordane. Many chemical combinations have been attempted over the past century in all invaded areas. In Australia, DDT, chlordane, dieldrin, and heptachlor were all used before being banned. The ants were often reduced in numbers, but never eradicated. These chemicals have obvious negative effects that would prevent their use in the future. Recently, bait traps have been used. They slowly poison the ant, allowing the carrier to bring poison back to its colony. Only one established colony has been eradicated (New Zealand). Since the ant is so prolific, it is very hard to eliminate once it has become invasive. Prevention and immediate action are the best methods to combat the spread of the ant.

References:

Argentine Ant: Factsheet. October 10 2000. (20 October 2004). Forest and Bird. http://www.landcareresearch.co.nz/research/biosecurity/stowaways/antfactv3.pdf .

Buczkowski, G., Vargo, E., and J. Silverman. The diminutive supercolony: the argentine ants of the southeastern United States. Molecular Ecology. 13(8): 2235-2242, August 2004.

California Academy of Sciences. 2004. (20 October 2004). Ants: Hidden Worlds Revealed. http://www.calacademy.org/naturalhistory/ants.html.

Fischer, R.N., A.V. Suarez, and T.J. Case. Spatial Patterns in the abundance of the Coastal Horned Lizard. Conservation Biology. 16(1): 205-215, February 2002.

Hee, J.J., D. Holway, A. V. Suarez, and T. J. Case. Role of propagule size in the success of incipient colonies of the invasive argentine ant. Conservation Biology. 14 (2): 559-563, April 2000.

Holway, David. Distribution of the Argentine ant (Linepithema humile) in Northern California. Conservation Biology. 9 (6):1634-1637, December 1995.

Holway, David. Role of abiotic factors in governing susceptibility to invasion: a test with Argentine ants. Ecology 83: 1610-1619.

Krushelnecky, Paul. April 2, 2004. (20 October 2004). HEAR Argentine Ant Harmful Non-Indigenous Species (HNIS) Report. http://www.hear.org/hnis/reports/hnis-linhum.pdf.

Krushelnycky, Paul and Andrew Suarez. April 20, 2004. (20 October 2004). Global Invasive Species Database, Linepithema Humile (Insect). http://www.issg.org/database/species/ecology.asp?si=127&fr=1&sts=.

Laakonen, J., R. Fisher, and T.J. Case. Effect of land cover, habitat fragmentation, and ant colonies on the distribution and abundance of shrews in Southern California. Journal of Animal Ecology. 70 (5): 776-778, September 2001.

Pacific Ant Prevention Plan. March 2004. (20 October 2004). Pacific Invasive Ant Group (PIAG) on behalf of the IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG). http://www.issg.org/database/species/reference_files/PAPP.pdf.

Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research. 2004. (20 October 2004). Linepithema Humile (Mayr) Argentine Ant Identification. http://www.landcareresearch.co.nz/research/biosecurity/stowaways/key/linhum_id.asp#Identification.

Robertson, Hamish. 2004. (20 October 2004). Linepithema Humile (Argentine Ant). Iziko Museums of Cape Town. http://www.museums.org.za/bio/ants/dolichoderinae/linepithema_humile/.

Suarez, Andrew, David Holway, and Ted J. Case. Patterns of spread in biological invasions dominated by long-distance jump dispersal: Insights from Argentine ants. PNAS. 98 (3): 1095-1100, January 30, 2001.

Tsutsui, Neil D. and Andrew V. Suarez. The Colony Structure and Population Biology of Invasive Ants. Conservation Biology. 17 (1): 48-58, February 2003.

Tsutsui, N. D., Suarez, A.V. Holway, D.A., and T.J. Case. Relationships among native and introduced populations of the argentine ant (Linepithema humile) and the source of introduced populations. Molecular Ecology. 10 (9): 2151-2161. September 2001.

Picture References:

Photo 1: http://waynesword.palomar.edu/ww0403.htm

Photo 2: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=14714

Photo 3: http://www.terro.com/ant_id2php

Photo 4: http://www.museums.org.za/bio/ants/dolichderinae/linepithema_humile/

Photo 5: http://www-biology.ucsd.edu/news/images/mcliz8.jpg (Chris Brown, USGS)

Photo 6: http://www.issg.org/database/species/ecology.asp?si=127&fr=1&sts=