|

|

|

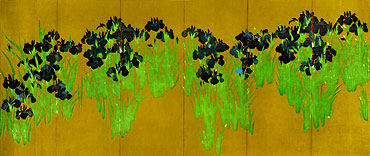

Perhaps the most popular-almost overfamiliar-design

in all of Japanese art is Korin's panorama of iris flowers spreading across

two golden screens. In ensemble and in detail this work has been reproduced

as frequently and abundantly as, shall we say, Botticelli's Primavera. And

perhaps for the same reasons: the same eternal appeal of rebirth in spring

and the same unfailing delight elicited by a painter's perfect assurance

in translating a force of nature into his own pictorial terms. Excessive

repetition may sometimes dull one's appreciation, just as one may feel an

excess of spring itself in the fullness of a lavish month of May. But a

few months later one is once more enchanted with the prospect of a new spring,

with another glimpse of the Primavera, with another encounter with those

myriad purple blossoms rising from a golden river . |

|

|

|

| |

| The exact date of the creation of the

iris screens has never been established, although it is usually placed around

1705. But a date is hardly needed, for one feels certain that this work

is a climax in the artist's development. It is the sort of work that can

be planned and executed only when a painter is so strong, so unhesitantly

assured, that he is able to pick up his brushes almost nonchalantly and

toss off a masterpiece that appears organically right, easy, flawless, and

unrestrained. Korin almost persuades us that he did nothing more than eavesdrop

on nature's own processes and whisk one of her fragments directly onto his

screens. |

|

| |

| In his last years, between 1705 and

1716, Korin was able to do just that. Into these culminating years of a

master's high maturity we must place this work that goes beyond even the

Red and White Plum Blossoms in its reductio ad ultimum. UntiI the present

owner brought this pair of screens to Tokyo in 1913, they were the property

of the Nishi Hongan-ji in Kyoto, and very Iikely they had been painted for

that same temple, which holds as much importance in the Iife of Korin as

the Daigo-ji did in the Iife of Sotatsu. We know that Korin often visited

the Nishi Hongan-ji and valued his connection with the abbot. |

|

| |

| The theme of irises growing along a

stream was derived from an ancient poem, in the characteristic literary

and painterly "renaissance" way of the Koetsu- Korin schooI. Korin undoubtedly

had in mind the "Yatsuhashi" poem from the "Azuma-kudari" chapter of the

Ise Monogatari, that inexhaustible romance of the tenth century which had

also occupied so large a share of Sotatsu's thoughts. The tale that became

a favorite subject for Korin's design recounts how the poet Narihira and

his companions on a long journey stopped to rest at Mikawa (in the present

Shizuoka Prefecture) beside a river bank abloom with irises. An old rustic

bridge of eight wooden planks reminded the weary travelers of a similar

spot in Kyoto, for which they expressed their yearning in a series of nostalgic

verses. Their sadness did not prevent them from turning their poetizing

into a game with a set rule that each line begin with a syllable from the

word for iris: kakitsubata. Here is Narihira's poem, with a translation

by Frits Vos: |

| |

| |

| Karagoromo |

As I have got a wife |

| Kitsutsu nare ni

shi |

To whom I have been

attached, |

| Tsuma

shi areba |

Just as

one gets used to and fond of |

| Harubaru

kinoru |

The skirt

of a beautiful garment |

| Tabi

o shi zo omou. |

While

wearing it-

I feel miserable about this very joumey

On which I have come so far. |

|

| |

| |

| The eight-plank bridge and the iris

flowers appeared often in paintings, ceramics, lacquer ware, fans, and other

artistic products of the Korin school. For his large interpretation on full-size

screens Korin selected the simplest statement, leaving out bridge and stream,

omitting such decorative accessories as lacquer and mother-of-pearl, and

confining himself entirely to the flowers against an abstract golden area.

He even left out his favorite device of ripping waves. Nothing but a streak

of purple flowers and green pointed leaves against the small shimmering

squares of gold foil that represent river and air and sky. |

| |

| Korin was an artist of so many facets

that no single work can contain them all, but Irises comes close to such

a summation. Typical is its start in literature and its termination in decorative

refinement. This range, which was also characteristic of the Koetsu-Sotatsu

interest, was pressed by Korin to the ultimate degree. Sotatsu had been

content to halt at a dramatic climax, where decorative considerations sustained

the literary stimulus yet remained subservient to the poetic or imaginative

ingredients. Korin relaxed the poetic thread and tightened the decorative

one. Perhaps one may forget that his iris flowers had their seed in the

Ise Monogatari and accept them directly for their flamboyant splendor of

color and their acute space relationships. In this regard Korin is more

"modern" than Sotatsu. He could almost qualify as a twentieth-century abstract

painter-almost as a forerunner of Matisse. This is stated neither in praise

not in blame but as a matter-of-fact recognition of their similarity in

aesthetic approach. |

| |

| |

| |

|

All images and information from

The Art of the Japanese Screen by

Elise Grilli.

Walker/Weatherhill, New York & Tokyo.

1970. .

|