In Berlin, Every Cheer Casts an Eerie Echo[1]

Hitler's Stadium is Remodeled

By Mark Landler

BERLIN - When two national soccer teams trot onto the grassy field in the Olympic Stadium here next July 9 to play for the World Cup title, few of the 76,000 spectators or the many millions watching on television are likely to dwell on the history of the place.

| Agence France-Presse - Getty Images |

The championship game will be riveting enough. The World Cup, which has its unofficial kickoff Dec. 9 in Leipzig with the final draw for the 2006 tournament, is the most popular sporting event in the world, eclipsing the Super Bowl and the Olympic Games.

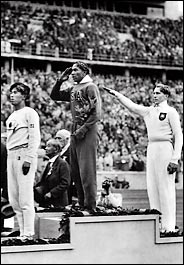

Yet history, as well as cheers, will echo from the stadium's limestone pillars and from the Marathon Gate, where Jesse Owens's name is chiseled in stone along with those of other champions. The 1936 Olympic Games opened here under the gaze of Hitler and the glint of swastikas.

| Bettmann/Corbis |

That Germany has chosen a place so freighted with symbolism to stage the World Cup final attests to how far it has come in confronting its past. Rather than build a new stadium, which would have cost less and catered to soccer fans, the Germans have reconstructed this landmark in a way that thoroughly modernizes it, while meticulously preserving its Nazi heritage.

"You can't overcome history by destroying it," said Volkwin Marg, a Hamburg architect whose firm oversaw the $283 million project. "We have to overcome our role in history by demonstrating it."

Germany, of course, will show off far more than this dark chapter of its past. Six months before the tournament begins, it is putting the finishing touches on $7 billion of construction projects throughout the country. It has built or refurbished 11 other stadiums, including an ultramodern new arena in Munich, with a translucent roof that looks like a quilted eggshell.

The World Cup will begin there on June 9 and unfold over a month in Leipzig, Hamburg, Frankfurt and other cities. With a million foreign visitors expected, it will be the largest sporting event since Germany's unification in 1990, and the most closely watched since the 1972 Munich Olympics.

With the facilities largely in place, Germany is turning its organizational skills to the less tangible aspects of being a good host. There are plans to stage an extravagant opening gala at the Olympic Stadium, with music supplied by the rock musicians Peter Gabriel and Brian Eno.

"The world expects Germany to be able to organize such a big event," said Wolfgang Niersbach, the executive vice president of the German organizing committee. "The important thing now is the atmosphere: what kind of host will we be? We want an atmosphere of hospitality."

But even here, history will play a part. André Heller, the Austrian impresario who is directing the gala, said he planned to make a reference to the stadium's Nazi history at some point during the festivities.

"This stadium was the set for Leni Riefenstahl's film," Heller said, referring to "Olympia," the famous documentary of the 1936 Games made by the female German filmmaker. "This was one of Hitler's great propaganda stages. We have to give an answer to that."

For the architects, the challenge was to transform a vast, decaying, mostly open-air arena, with rows of concrete benches, into a partly covered modern stadium, with roomy seats, luxury skyboxes, parking and a news-media center. They had to do this, while retaining the stadium's monumental design - perhaps the most enduring example of architecture from the Nazi period.

"It's like turning a Greek amphitheater into La Scala in Milan," said Marg, whose firm has designed stadiums in Cologne and Frankfurt, as well as the soaring new central train station in Berlin.

The centerpiece of the design is a spectacular steel-and-glass roof that shelters the seats but not the field. Like the stadium, it is not a closed ring, but remains open in front of the Marathon Gate. This enables spectators to see a bell tower that keeps watch over the stadium.

For engineering reasons, the gap necessitates a series of slender steel columns to support the roof - a design quirk that has drawn jibes from fans because it mars the view from some seats.

With its playing field sunken into the ground and the precise rows of pillars, the stadium evokes "a place of ancient drama or consecration," said Dieter Bartetzko, a German architecture critic.

Marg said he tried to remain faithful to that concept by tucking the skyboxes unobtrusively between the first and second section of seats. Hospitality suites, bars, restaurants and a private parking garage are hidden under the stadium. The news-media section is in what used to be a bunker.

| Lutz Bongarts/Bongarts - Getty Images |

"What we had to do was to change a people's stadium into a class stadium," Marg said. "During Nazi times, there was only one V.I.P. Today, there are several classes of V.I.P.'s."

The tribune from which Hitler watched the opening ceremony in 1936 - and exchanged a wave with Owens - still exists, though the seats have been removed and a railing keeps out the curious.

The decision to reconstruct the stadium came after a lengthy debate, though not because of its dark historical associations. Largely undamaged in World War II, the stadium has been used for concerts and as a home field for the city's Bundesliga club, Hertha BSC Berlin. The stadium was used during the 1974 World Cup, which was held in and won by West Germany, but not for the final.

Some renovations were done in 1969 and 1974, and Berlin made the stadium part of its unsuccessful bid for the 2000 Olympics. By the end of the 1990's, however, it was decrepit and in need of a radical overhaul. With its track and its gently sloped stands, it was not well suited to soccer.

A new arena would have allowed Berlin to compete with rivals like Cologne or Dortmund, which have soccer stadiums, with the seats stacked around a rectangular playing field.

"The Berlin stadium is too big," said Rainer Holzschuh, the editor in chief of Kicker, Germany's leading soccer magazine. "You sit too far back from the pitch. There is no atmosphere."

The trouble is, the Olympic Stadium could not be demolished because of its landmark status. Berlin did not have use for a second stadium, officials said, and maintaining this one, empty, would have been too expensive. In 1998, two years before soccer's governing body, FIFA, awarded Germany the World Cup, the Berlin Senate voted to reconstruct the stadium.

"This wasn't an ideological debate; it was a fiscal debate," Hans Stimmann, the city's director of urban development, said.

| Associated Press |

While pragmatic, Berlin's decision was also in keeping with a political trend since the fall of the Berlin Wall: to refurbish rather than to tear down Nazi buildings. The German finance ministry occupies the onetime headquarters of the Luftwaffe, and the foreign ministry is in the old Reichsbank.

Each displays pictures and other records in its lobby, documenting how it was used during Nazi times. The ground-floor galleries that surround the exterior of the Olympic Stadium are similarly labeled. One placard describes how the stadium's architect, Werner March, decided to use limestone because the Nazi regime considered it the original German stone.

"We have a renovated stadium and we have a political and cultural commentary," Stimmann said.

There are plans for more commentary in a ceremonial building near the stadium known as the Langemarckhalle. Modeled on an Egyptian temple and named after a World War I battle in which thousands of German soldiers perished, the hall was used by the Nazis to illustrate their notions of the link between heroics on the playing field and on the battlefield.

Workers are reconstructing the building to house a museum that documents the use, and misuse, of sports during the Nazi era. The clock tower above it is also being reinforced. Between it and the stadium is a field, which will be the site for the hospitality tents of World Cup sponsors.

To reach these symbols of big-time modern sports, guests will pass through the hall, where, the architects hope, they will pause long enough to reflect on how sports was exploited in the not-so-distant past.

"The Nazis saw sports as a preparation for war," said Michèle Rüegg, an architect in Marg's firm who worked on the project. "Explaining this is incredibly important."