|

Arab

Merchant

|

|

by

Kirsten Grieshaber

|

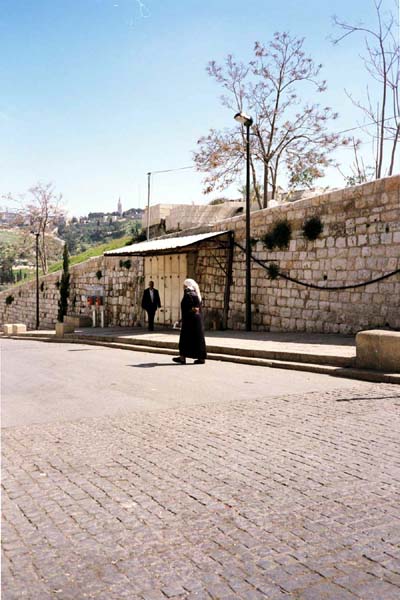

The Arab market in the Old City of East Jerusalem is deserted on this Shabbat afternoon. Only a forlorn-looking Swedish couple is walking down the dark, narrow streets to the Western Wall, passing an elderly Arab woman her head covered with the hijab-a white veil. The most common passers-by are groups of Israeli soldiers, their uzzis dangling over their shoulders. Concerned about the safety of the few remaining tourists and pilgrims, the soldiers are blind to the treasures of Basim Ju'beh's little store on David Street in the Old City.

Sitting idly on a small plastic stool in a corner of his shop, Ju'beh bends over to straighten a box with ground ginger. The Palestinian merchant sells 36 different sorts of spices, all neetly arranged in blue plastic boxes. Rosemary and cardamon, nutmeg, pepper and cloves, cumin, saffron and allspice were once to be his bestsellers.

But not any longer.

Since the beginning

of the second Intifada, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict that started

six months ago, Ju'beh's income dropped more than 90 percent.

|

"Shabbat used to be the best day, I was busy selling my spices to Jews,

Arabs and tourists all day long," the 36-year-old recalls, adding that

now, nine out of the ten hours that he is at work each day, he gets

no customers.

The current conflict has halved Palestinian incomes and tripled unemployment, according to the Palestinian Authority. American diplomats and United Nations envoys have warned in recent weeks that without financial support the Palestinian Authority faces imminent bankruptcy.

"The Palestinian economy is on the brink of collapse," Martin Indyk, the American ambassador to Israel, was quoted in the New York Times earlier this month.

Ju'beh has to face the economic consequences of the new Intifada every day, as tourists, afraid of suicide killers and bus bombings, stay away. Without any stable income for the past six months, Ju'beh spent most of his savings to feed his family. Even then the father of four could only afford to buy the very essentials and has a hard time paying his bills. Compared to others, however, he's still in good shape.

"I know lots of storekeepers who hadn't saved enough money," he says. "They had to close their shops and now they work restaurants, cleaning the floor."

Ju'beh estimates that his savings will see him and his family through for two more months. Ask him what he will do once his money runs out, and he shrugs:

"Inshallah, only God knows."

Inspite of his bleek prospects, Ju'beh supports the Intifada. As Jewish settlements in the Palestinian territories remain and Israel continues to deny the refugees' right to return, Ju'beh says, his people have to keep on fighting, even if this means the end of his business.

"You are giving land to Jewish people who left it 2000 years ago, but don't want to return it to Palestinian refugees who were driven off their land only 50 years ago," he says, claiming that his father still keeps the keys to his former house in Hebron, which he had to leave in 1948.

As Ju'beh complains about the Israeli government "It's not the people, it's Sharon I really hate. I used to have many Jewish customers, they were friends of mine," a group of Mexican pilgrims enters his store.

Suddenly, the stubborn and unforgiving expression on his face disappears and politics doesn't matter anymore. Ju'beh is all charming again, addressing the five women in fluent Spanish, making them smell the different spices and taste the dried dates. His friendliness pays off when the women leave ten minutes later, with bags full of saffron, pizza spice and curry.

"At least I've earned some money today," Ju'beh says.

For the first time the businessman smiles, counting the shekels in his palm. As night falls, the Shabbat is about to end and the muezzim calls for prayer, Ju'beh closes his shop. He pulls down the metal shutters and treats himself to a cup of coffee, before returning home. He boils water in a small brass pot, adding freshly ground Turkish and Arab coffeebeans, a pinch of cardamon seeds and two teaspoons of sugar to it. Soon his little store is filled with the aromatic smell of Turkish coffee, suppressing even the intense fragrance of spices, incense and dried fruit.

"I have a dream," Ju'beh says, sipping his coffee.

"I would like to see Jerusalem become an example for the world. I want Christians, Jews and Muslims to live together peacefully in this holy city. After all, we shouldn't forget that we all pray to one and the same God."