|

A

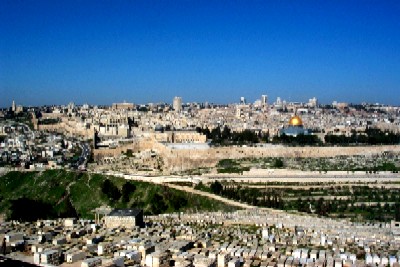

Room With A View . . . Of The Western Wall

|

|

by

Michael Petrocelli

|

|

At first glance, it appears that Elyah Docheff has been coming to the Western Wall for a long time. His attire-white shirt, black jacket, black slacks, black shoes, and black felt yarmulke-make him look right at home among the many Jews in traditional dress who mill about. "I consider myself Hasidic," he says standing next to the Kotel, the area in front of the wall where hasidic Jews and members of other ultra-orthodox sects are gathering for their Saturday morning prayers. After his prayers are finished, he will walk to Mea She'arim, the ultra-orthodox section of Jerusalem, for lunch with a Hasidic family. He looks the part. Along with his garb, he wears peyis, curls of hair near the temples that he has wrapped around his ears, and a scissor-trimmed beard. Just one year ago, Docheff, 24, lived in Washington, D.C., where he worked as an aerospace consultant. One year before that, he says he had little interest in his Jewish roots, but after an Orthodox woman turned him down for a date because he didn't observe Jewish law, he decided to attend classes. The woman is long gone, but his desire to learn about Judaism has continued to deepen.

After a year of study in Washington, he decided he needed to go to the source and moved to Jerusalem. He now lives and learns at Aish Ha Torah yeshiva, an organization with a prime piece of real estate just steps from the Western Wall. From his room at the yeshiva, Docheff can peer out at the wall, a remnant of the platform on which the second Jewish temple sat until it was sacked by Roman troops in A.D. 70 and one of the most revered sites in Judaism. Or he can look up onto the platform where the golden roof of the Dome of the Rock, the third holiest site in Islam, glitters under both sun and moonlight. Docheff's eyes narrow slightly behind his small glasses as he talks about his family's reaction to his changes. He recently went to New Jersey for six weeks to stay with his parents, and he says that the strains were unbearable by the end of the trip. His appearance was a shock, and his insistence on following certain parts of Orthodox Jewish law, particularly the prohibition on touching between men and women, were incomprehensible to his parents. They couldn't understand why he suddenly refused to hug his female cousins. His mother was initially happy to accommodate his desire for kosher food, he says, even buying a new set of plates for him to eat from, but eventually grew tired. "After five weeks, my mom was frustrated thinking I was looking over her shoulder while she cooked." He makes the short walk outside of the yeshiva, past the tourists snapping pictures of the holy sites, and through a security checkpoint to get to the wall. He is looking for a group of Ashkenazim, Jews of Eastern European extraction, whom he can join to say the Kaddish, the mourner's prayer, for his recently deceased grandfather. He walks through the tunnel just north of the Kotel plaza straining his ears for a familiar style of prayer, but finds only the unfamiliar sounds of Sephardim, Jews with roots in the Mediterranean. Eventually finding a group he is comfortable with, Docheff, who changed his name from Jason to the Hebrew Elyah, stands on the fringes of the minyan, a group of 10 men that constitutes a quorum for prayer. He moves his body less confidently than the others, who bow feverishly and throw their heads back at various points in the prayer. While he looks the part, he is clearly a neophyte when it comes to prayer, keeping his nose in the prayer book to follow along. Docheff knows that he is living in a tense place, especially since the start last fall of the second Intifada, the name many give to the Palestinian uprising. He says he was praying at the wall last October when Palestinians began raining rocks on the Kotel from the platform above. "These weren't little pebbles," he says, "these were big stones. We all just covered our heads and ran into the tunnel." Even having seen the danger firsthand, Docheff remains sanguine about the current state of affairs in Israel. He says that if anything, the conflict has strengthened his resolve to remain in Jerusalem and that Aish HaTorah. Other yeshivas catering to non-Israelis say that they have seen a surge in enrolment since the violence started. "You go into all the yeshivas now and the places are just buzzing," he says, rapidly jackknifing his body to demonstrate the frenetic energy of prayer the conflict has inspired in the religious schools. "Thanks, Intifada, for that."

|