A Double-Edged Stereotype

Charismatic Catholics combat dual discrimination

By DANIEL BURKE

|

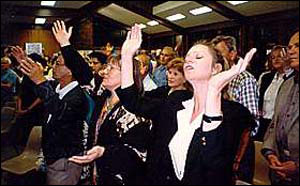

| Around the globe, Charismatic Catholics attend conventional Catholic mass but also hold weekly prayer meetings where they sometimes get "slayed" by the Holy Spirit. PHOTO: Courtesy of the Archdiocese of Melbourne, Australia |

A Catholic priest wearing a bright blue cowl, silver crucifix and wide smile is speaking in French to a circle of 40 ruddy-cheeked young Russians. They are scrunched against walls, seated on cushions on the floor, and perched on top of a piano. A woman sitting next to the priest is translating his French into Russian. He is talking about the new Christian movements springing up around the world.

"The Holy Spirit invents all the times," he says. "He's a big inventor, with a large imagination."

The host of the gathering, Irina Chernyak, flits about the periphery of the circle. She rubs her hands together, looks around nervously, and smiles wanly when meeting a gaze.

Chernyak is the one who invited this Catholic priest, the Rev. Daniel Ange, to speak to the predominantly Orthodox youth group she founded in 1991, Christian Club Hosanna. But to watch her jittery behavior is to somehow be reminded of Moscow's history of samizdat presses, refuseniks and persecuted priests.

It's not what Ange says or does, it's the fact that he's a Charismatic Catholic that puts Chernyak on guard.

"There is a very negative attitude towards charismatic groups in Russia," Chernyak says, explaining her nervousness.

In the homeland of the Russian Orthodox Church, Charismatic Catholics have two strikes against them. While they are accepted by the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, some Charismatic practices make it difficult to distinguish them from Protestant evangelists.

A bear that's just awakening after a 70-year slumber, the Russian Orthodox Church jealously guards its turf. Orthodox Russians, laity and clergy alike, often accuse Western priests and missionaries of poaching on that turf: luring away young Russians who might have been part of their Orthodox tradition were it not for decades of state-enforced atheism.

"Russia has been burned by mercenary missionaries," says Peter Bouteneff, a theologian at St. Vladimir's, a Russian Orthodox seminary in Crestwood, N.Y., "and that, unfortunately, has cast a shadow on other Christian groups that are in Russia."

He says Russia was swarming with well-funded and aggressively proselytical groups after the fall of communism. These groups set a bad precedent.

Among the groups Bouteneff cites as having "burned" Russia are American Baptists and Pentecostals, who draw converts with an exuberant devotional style, promises of a personal connection with God and dollars.

"The Russian Orthodox Church is very concerned about proselytizing, about appealing to the young people," says the Rev. Ronald G. Roberson, associate director of the U.S. Bishop's Committee for Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs.

"The Orthodox sees them as particularly liable to this kind of appeal," Roberson says, referring to the attraction to Western Christian groups who emphasize a personal, almost informal relationship with God.

"I've read manuals, written by Baptists, that teach them how to convert other Christians in Russia," Bouteneff says. "Baptists and other Protestants have sent millions of dollars to Russia to offer as financial enticements to join their congregations."

Though they keep a low profile, approximately 400 Russian Charismatic Catholics have emerged recently in Moscow, according to the Rev. George Jagodzinski, a Catholic priest who lives in the city. Although they mostly meet underground, these groups have caught the attention of the Russian Orthodox Church, he says.

"This is a new step and it makes them (the Russian Orthodox) very nervous," Jagodzinski says.

According to Jagodzinski, Charismatics in Moscow are, for the most part, young and well-educated. But the media in the city have often characterized them, and those who host Charismatic leaders, as backward and mentally imbalanced.

Much of that has to do with their hybrid and unorthodox practices. Like the Pentecostals, Charismatic Catholics speak in tongues. And although they baptize infants in keeping with Catholic dogma, like Baptists, they believe the sacrament is best performed on adult believers, who are fully conscious of its implications. They perform a second baptism later in life, in which the Holy Spirit "stirs the soul."

Charismatics attend the Catholic Mass on Sunday. But they also hold prayer meetings once a week, during which they sing lively songs, testify to the presence of Jesus in their lives, and sometimes roll on the floor when overcome, or "slayed" by the presence of the Holy Spirit.

When Pentecostals, Baptists and Charismatic Catholics exhibited such behavior in Russia in the late 1990s, they were accused of hypnotizing their congregations by the Russia media and some Orthodox prelates. This is perhaps why, at the prayer meeting, Ange is subdued.

The situation is such that many Western Charismatic Catholic groups, who travel across the globe, will not visit Russia without an invitation.

"It's a bit of a hot potato," says Peter Herbeck, vice president and director of missions for Renewal Ministries, a Charismatic Catholic evangelical group based in Michigan. The group has traveled to 25 countries, including Syria and Nigeria, but has no plans to go to Russia until the situation there changes, Herbeck says.

"We have not gone over there because they are so sensitive to evangelization," Herbeck says. "Even the Catholic priests in Russia, who were born there and have lived there all their lives, are themselves very sensitive to evangelizing. They don't want anybody from the West to come unless they are invited."

Bishop Seraphim Sigrist, of the Orthodox Church of America, is a spiritual advisor to the Hosanna group in Moscow. He believes that the resistance to Christian movements outside the Orthodox Church in Russia is part of an effort "to prove how Orthodox one is" by purging the country of those who are "found to be doctrinally impure."

"There is a good deal of that in our Church," he adds. "That is to say, people drawn to Orthodoxy by the idea that here is a principal of order where we can be right and everyone else wrong."

But some American Catholic leaders are more sanguine about the prospects of Russia opening up to diverse expressions of faith. The Russian Orthodox Church just needs to get back on its feet, says the Rev. David Carroll, of the Catholic Near East Welfare Association. "Once they have done that, I think they will be much more open to other Christian groups in the country."

QUICK

LINKS:

Feature

Stories | Dispatches

| Photo

Essays |

Itinerary

& Maps

|

About

This Class

A project of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism made possible by the Scripps Howard Foundation. Comments? E-mail us.

Copyright

© 2003 The Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University.

All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission

is prohibited.