New Old Believers

Russians discourage assimilation, U.S. church accommodates

By SARA LEITCH

|

|

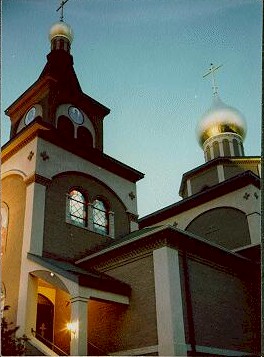

The cupolas of the Old Rite Russian Orthodox Church of the Nativity in Erie, Pa. bear remarkable resemblance to the belfries of Rogozhskoye Monastery in Moscow. PHOTO: Courtesy of Church of the Nativity |

Palm

Sunday, which commemorates Jesus' return to Jerusalem one week before

his crucifixion, is known as Willow Sunday in the Russian Orthodox Church.

At Willow Sunday services, congregants carry small bundles of pussy willow

branches and burning candles.

"The only thing that blooms that early in Russia is pussy willows,"

said the Rev. Pimen Simon, a priest at the Old Rite Russian Orthodox Church

of the Nativity in Erie, Penn. "But in America, you can get palms

any time of the year. So now some people carry palms and other flowers

as well as willows."

In the same way that his parishioners' willow bouquets have adapted to include flowers available in the United States, Simon has helped his church adapt to life here. Church services are held almost entirely in English instead of the traditional Old Slavonic, converts from other religions are welcomed and young people attend Sunday school classes and participate in many aspects of church life.

But the adaptations come with a cost, say Russian Old Believers. Younger generations in the U.S. are losing much of the Old Believer heritage that the Church in Russia holds so dear. Many of the Old Believer brethren in Russia don't approve of the assimilation abroad.

"The old generation probably keeps tradition even more strongly than in Russia," said Mikhail Roschin, an Old Believer and professor of Religious Studies at Oriental University in Moscow. "The younger generation is in some way lost. They failed to give knowledge to the younger generations. The children are in American schools, learning in different places."

The newness of Simon's church does in a way seem counterintuitive, as it is a member of the Old Believers, a sect of Russian Orthodoxy that appeared more than 300 years ago when the tsar modernized the church's books and practices.

Old Believers refused to change their liturgy, holding on to their traditions in the face of government persecution. There were splits within the group, as some congregations accepted priests ordained by the mainstream church, while others held that any person ordained using the new rituals was not truly a priest.

Immigrants from Suwalki, a small town that was part of the Russian Empire but is now in Poland, founded the Erie congregation in the 1880s after they came to Erie to work on the docks of Lake Erie. Their church, with brown-painted walls and a gleaming gold dome, sits on a hill overlooking the water.

The immigrants were priestless Old Believers, whose services were led by a novostnik who could not perform the sacraments but attended to the other spiritual needs of the congregation. The Rev. Simon served as a novostnik at the Erie church in the 1970s and 80s before deciding that the only way forward was for him to become a priest and perform services in English.

Not everyone in Erie agreed.

"About 20 percent of the parish violently opposed that movement," Simon said. "But we had almost no young people, and really no future."

As the sun set during services on the Saturday evening before Palm Sunday, the church filled with the scents of incense, candle wax and flowers, and young people were highly visible members of the congregation. Teenagers led the recitation of the liturgy and toddlers stood at the front of the line of church members waiting to venerate the Palm Sunday icon, one of the requirements they needed to fulfill if they wanted to take Communion on Sunday morning.

During the Saturday evening matins service, everyone from the youngest children to old women stood patiently in two lines to venerate the icon. When they reached the front, they handed their willow bouquets to a young deacon. Then, they participated in a highly synchronized ritual of crossing and prostrating themselves before the icon and the Bible which sat on a table covered in black velvet. After the priest drew crosses on their foreheads with holy oil, they bowed to each other, collected their bouquets from the young deacon and moved aside.

The act of worship was so well-coordinated that it took a little more than 30 minutes for the priest to get through each of the 200 congregants. At the end, the priests themselves also performed the ritual, then continued with the service. All the while, male and female choirs chanted.

This traditional emphasis on worship combined with the new English-language services is attracting new Old Believers.

Stephen Maynard, 26, joined the church two years ago, after a few dates with a Jehovah's Witness sparked his interest in religion. Maynard, who was raised Catholic and served as an altar boy as a teenager, began visiting different churches in Erie, trying to decide which one to join.

"Most places, everyone would hang out while somebody would talk to you," he said. "Something about the Old Believers attracted me. It was more worship-oriented. The priest started out the service by saying that he is the chief sinner and worse than everyone else."

Maynard says he enjoys the familial atmosphere of the congregation, both during services, and outside of church.

"The church is very tight-knit, everyone knows everybody, it's like a family," he said. "And I'll probably never go hungry again in my life. The old ladies bring me food, and they're always trying to fix me up with their granddaughters."

Although the Erie church has converted most of its service from Old Slavonic into English, it still attracts some Russian-speaking immigrants looking to attend Old Rite services in the United States. One of these new members is Yelena Spektor of Pittsburgh, moved to the United States from Russia three years ago.

"The reason why she came to America is just marriage, but she's trying to keep her old religion, the religion of her parents," said her husband Dennis Spektor, translating for his wife. Yelena Spektor's father, Mikhail Zadvornov, is a priest at an Old Believer church in Novosibirsk, the capital of Siberia.

"He goes to the church every day, he's a very hard worker," Dennis Spektor said. "He's built a new church."

He said that his wife had asked him about Old Believer churches when they first met through an online dating website. When relatives in Long Island told her about the Church of the Nativity, Dennis Spektor vowed to drive his wife the two hours it takes to get to church.

"That's

why my wife always goes to Erie, that is the exact church she used to

go to in Russia," Dennis Spektor said. "A lot of people go to

Russian Orthodox Church, but as far as I can see there is some difference

between Old Believers and Russian Orthodox. They are a special kind of

people, just like Jewish Orthodox people."

QUICK

LINKS:

Feature

Stories | Dispatches

| Photo

Essays |

Itinerary

& Maps

|

About

This Class

A project of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism made possible by the Scripps Howard Foundation. Comments? E-mail us.

Copyright

© 2003 The Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University.

All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission

is prohibited.