===

0553,

4

===

=== |

|

FWP:

SETS == EXCLAMATION; KYA

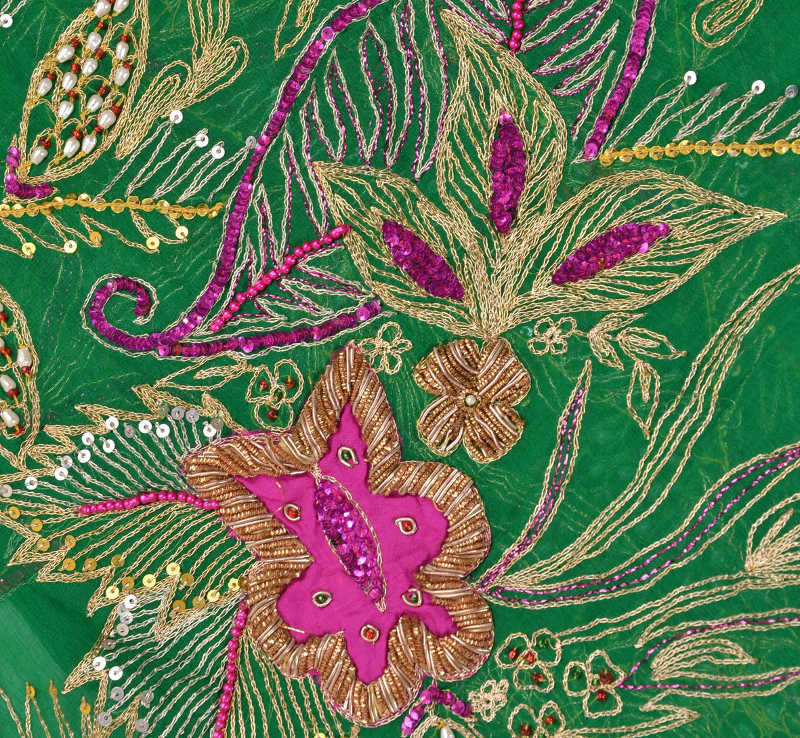

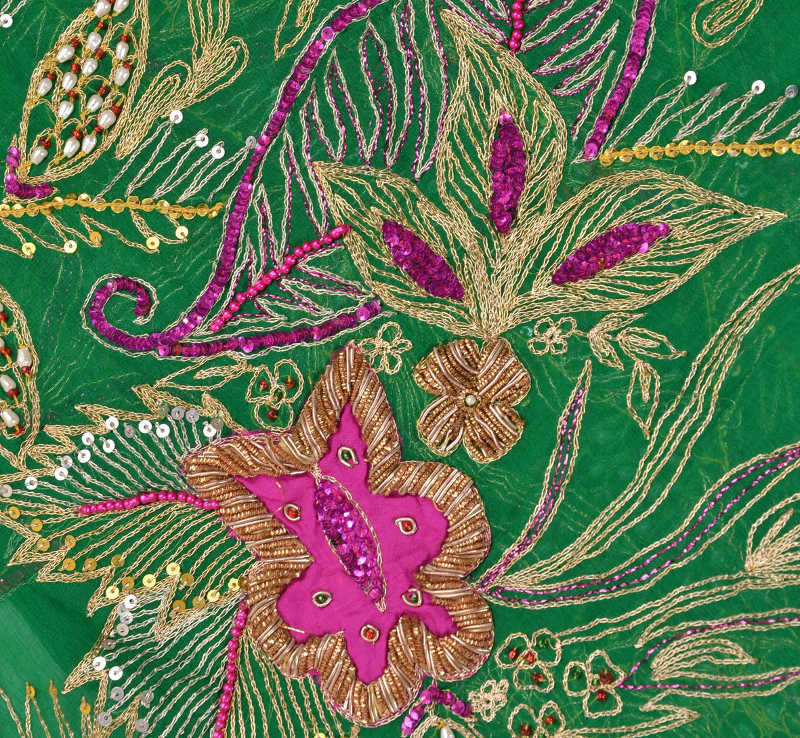

MOTIFS == SPRINGTIME

NAMES

TERMS == INSHA'IYAH; THEMEThe insha'iyah observations that SRF makes at the end of his discussion can be pushed even further. For the 'kya effect' reasons that operate in the first line, so that it can be read not only straightforwardly ('Whose desire has been fulfilled?-- Someone's obviously has!') but also as a negative rhetorical question ('Whose desire has been fulfilled?!-- No one's, of course!'), are operative in the second line as well.

In fact the second line can be read in even more fully multivalent glory: 'How many wandering feathers have come into the garden-- there are such a lot of them!'); or 'How many wandering feathers have come into the garden?-- it's really hard to tell'); or 'As if any wandering feathers have come into the garden!-- how absurd an idea, when not even the leftover feathers of the longing bird are destined to make it into the garden!').

Mir versus Ghalib-- it's like the Iliad versus the Odyssey, or Plato versus Aristotle, or Herodotus versus Thucydides. Anybody with any literary sensitivity and judgment is entirely grateful for the riches of both. Still, deep down most people have something temperamental that goes one way or the other. Nowadays SRF is an unabashed Mirian; he may concede that the two are equally great poets, but he will always go on to point out, rightly, that Mir has a far wider range. I remain a Ghalibian, because Ghalib somehow cuts deeper. Mir has all kinds of poetic magnificences, but Ghalib... at his best, he makes waves of sheer exhilaration run through my heart and mind.