FWP:

SETS == KYA; MUSHAIRAH

FOOD: {6,4}

Some manuscripts, and some modern editions, have rahe;N instead of rahe in the second line. As always, I follow Arshi. See his discussion in his introduction, p. 123. (The grammar shows the idiomatic use of the perfect instead of the subjunctive.)

The first line sets up a strange and piquant situation-- a drought, a scarcity, a crop failure, of the 'grief of love'? And located in a particular area, just like a real drought? It's tempting to guess, because of the abstractness of the 'grief of love', that the qah:t should be read in only a very general sense-- a scarcity, a shortage, a lack. How will the second line resolve the situation? Under mushairah performance conditions, of course, we'd have to wait as long as conveniently possible before we'd be allowed to find out.

The second line remains notably uninformative for as long as it possibly can. 'We agreed that we'd stay in Delhi'-- how does that help? Then in classic mushairah-verse style, at the last possible moment the punch-word is finally vouchsafed to us-- that excellent khaa))e;N . When the original audience heard khaa))e;N kyaa , surely they must have burst out laughing. Because of course the connection suddenly is made in the hearer's mind, with a shower of sparks-- that in Urdu one literally 'eats' grief [;Gam khaanaa]. So to the mad lover, a drought or scarcity or shortage of grief is just as dire as a real lack of food, and the qah:t is in fact a real famine.

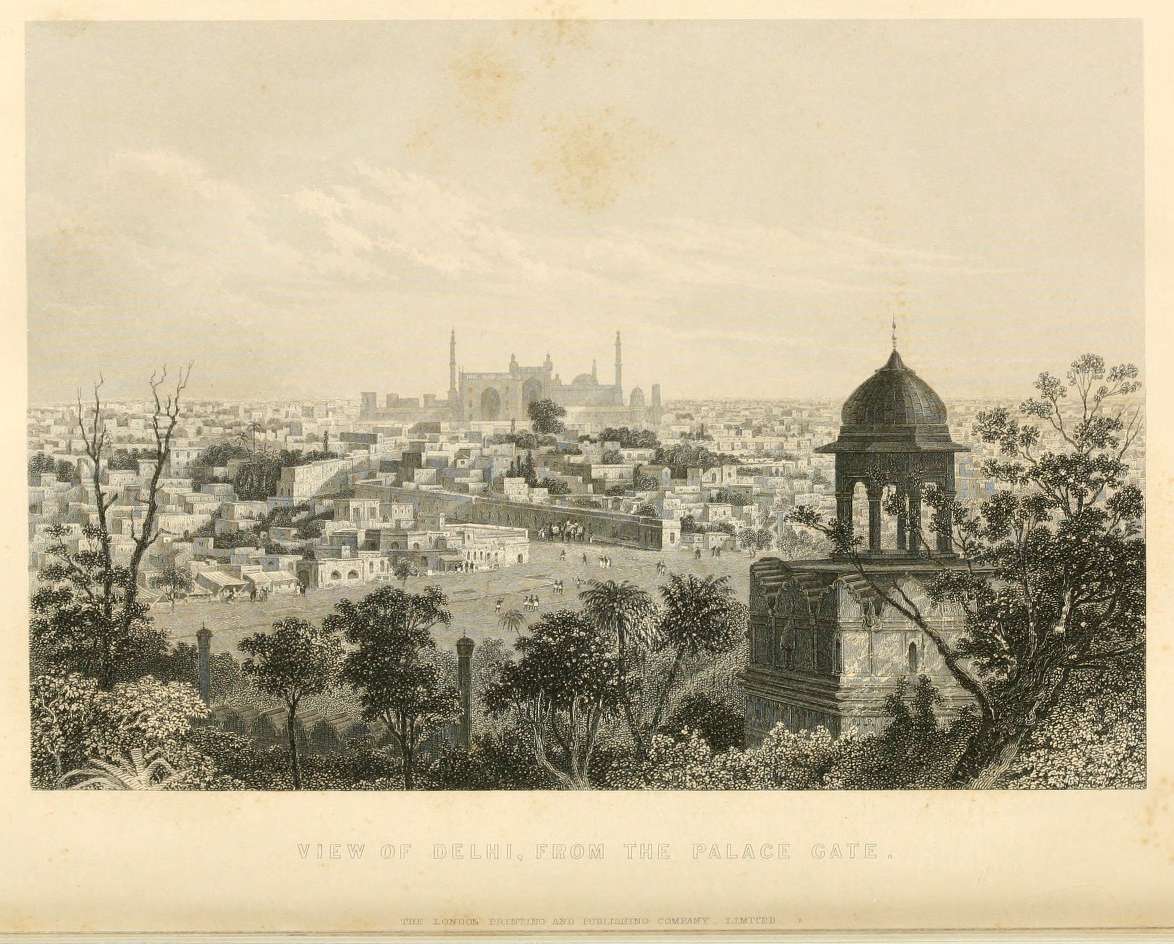

When it comes to food, the verse sets up an implicit contrast between the city and the desert, the usual haunt of wild lovers and madmen. Hunger in the desert is almost de rigeur (think of the skeletal Majnun); in the desert there's a famine of food to eat, while in this well-peopled, pleasant city (see the definition above) there's a famine of grief to 'eat'.

The first part of the second line [ham ne yih maanaa] suggests that the speaker has been (reluctantly?) persuaded to remain in Delhi, at least half against his will, and feels inclined to be perverse about it. He thus raises practical objections. For having a steady diet of grief to eat is obviously as important to the lover as having a steady diet of food to eat would be to anybody else. How can he live in a place where he can't 'eat'?

Thus we're led to ask ourselves whether the big city and the desert are more similar (both lack the wherewithal for 'eating') or more different (a famine of grief amidst a crowd, versus a famine of food in solitude).

It's rare for Ghalib to mention anything as specific, as 'real', as a city in the world, and that too the one he actually lives in. Of course, he doesn't go so far as to give us any genuine information about it-- it becomes a ghazal city, distinguished only by its temporary ('now') grief-famine. The fact that even something as minimal as a place name stands out so vividly shows how deep in the realm of stylization and abstraction the ghazal itself lives.

And for a more extravagant foray into the wordplay of 'eating' grief, compare Mir's M{608,5}:

za;xm bin ;Gam bin aur ;Gu.s.sah bin

apnaa ;xaanaa ;haraam hotaa hai

[except for wounds, except for grief, and except for anger

our 'eating' is religiously prohibited]

Nazm:

We have learned to experience the relish of 'eating' grief, and that is not available here; that is, in this city there are no beloveds for whom passion would be felt. (20)

== Nazm page 20