FWP:

SETS == EXCLAMATION; JO; MULTIVALENT WORDS ( rusvaa ); PARALLELISM

ABOUT rusvaa : To be rusvaa in Urdu is to be disgraced, dishonored, etc. To be rusvaa in Persian, however is also to be 'open, notorious', 'held up to public view'. (See the definitions from Steingass and Platts above.) Ghalib's use of the word often plays on the especially Persian sense of exposure, disclosure, public humiliation, as in the present verse. More examples of

meanings that seem to include this Persianized sense: {68,10x}; {95,4};

{126,3}; {130,4};

{139,7}; {148,3};

{149,5}.

The verse has a four-part structure. Each line contains two parallel phrases that end in an internal rhyme and correspond exactly to the metrical quasi-caesura. This gives it unusual energy and a kind of exclamatory force.

It's also a showcase for the multivalences of the protean little jo . These are so conspicuous that Platts is careful to give it three separate definitions (see above). Try reading the first line with each of the four possibilities recommended in the translation; each is different in its own way, and each one works in the line, and also with the second line. Ghalib was fortunate in the grammatical tools available to him. For more on jo , see {12,2}.

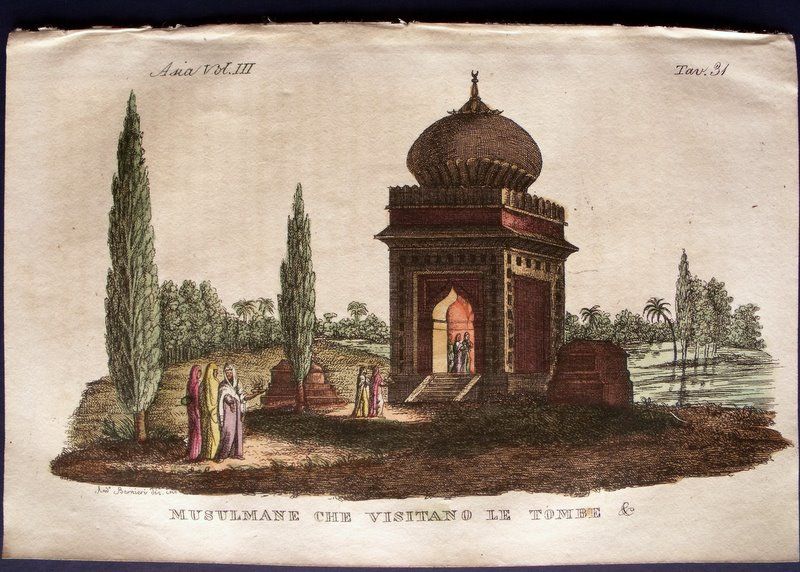

Traditionally, Muslims especially fear death at sea, because if the body is lost one cannot have the proper funeral rites, nor can one lie in a suitable grave waiting for qiyaamat , the day when the dead are summoned to rise up for divine judgment. But for the lover, of course, all this may be reversed. Here the lover's death is an occasion of disgrace to him, such that he wishes he could undo it all-- no funeral procession to generate fresh gossip, no tomb to remind people of his notoriety and shame.

Why was he disgraced? Because, as Bekhud Mohani says, he was shown up by death to be an inferior lover with limited powers of endurance? Because rumor reported the name of the beloved for love of whom he died, so that the beloved was angered by the publicity? Because he didn't have the beloved's permission to die, so that he was disgraced in her eyes by his disobedience, as in the similar situation in {9,3}? As usual, the answer could well be-- all of the above.

This is a verse in which the dead lover somehow, from beyond

the grave, still speaks; for other such verses, see {57,1}.

Nazm:

That is, the forming of a funeral procession and the making of a tomb have disgraced us; it would have been better if we had drowned. (21)

== Nazm page 21