FWP:

SETS == MUSHAIRAH

In castigating the address to 'Weeping', Nazm doesn't give Ghalib sufficient credit for the clever use he makes of inshaa))iyah speech. For when the lover addresses 'Weeping', he might be making a complaint ('All this is your fault!'); or an apology ('Sorry, I've got nothing left to weep with'); or perhaps just a matter-of-fact report to one of the few companions he has left ('Well, it looks as if my end is approaching'). As so often, it's left up to us to decide.

And what is the content of the complaint, or apology, or report? A compressed but thorough litany of debilitation. Out of all the blood that used to be in the speaker's body, none is left. Some of it took the form of 'color'. On one reading, this was the color in the face (that in fact comes from blood vessels under the skin). Not satisfied with that degree of attenuation (from blood to mere color), it then promptly 'fled'. (Fortunately for the translator, it's possible to say that someone's 'color fled' in English, just as in Urdu, to mean that the face became pale.) The wordplay that envisions color 'taking flight' from the lover's face is reminiscent of the clever {7,2}.

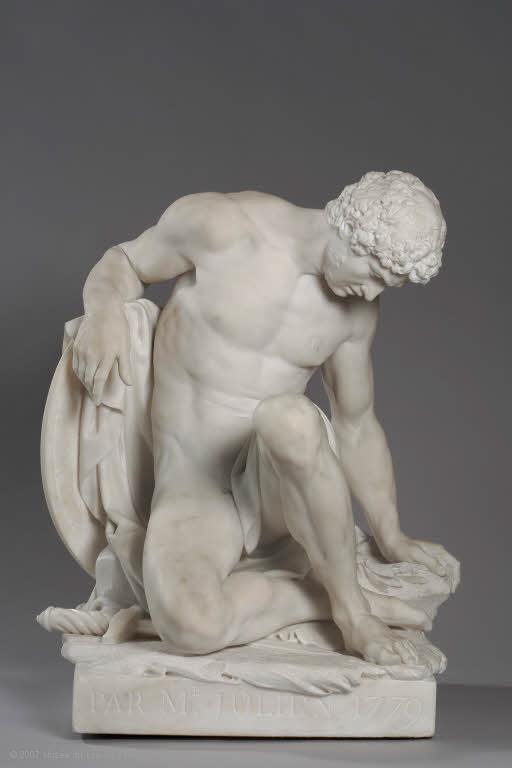

The rest of the blood that has not turned into color (and fled or faded) is now reddening the speaker's garment-hem. Only by suggestion do we know that this means it has been shed in the form of tears of blood. And why are the tears on the garment-hem, instead of, say, the collar or the sleeve? Because the lover is so weak and depressed that he spends his time sitting in something like a do-zaanuu way, on his haunches, with his head lowered; for discussion of this position see {32,2}.

This would be an amusing mushairah

verse because of the deftness of that last half of the second line. The first

half of the second line reports a rather minor, common kind of metaphorical-only blood loss--

blood (metaphorically) turns to color and then flees or fades. Only in the second half of the line do we learn, in a casual,

afterthought, by-the-by way, manner, that the blood that was lost in that

fashion was (only) the blood that is not now located in the garment-hem. In

other words, the real damage was done by the constant shedding of tears of

blood. So only now, at the very end of the second line, can we really tell

why 'Weeping' was the addressee in the first line. All this information is

conveyed only by the word daaman , which is, in true

mushairah style, withheld until the last possible moment.

Nazm:

From the word 'weeping' the meaning emerges that the blood that's in the garment-hem is bloody tears. But to address 'Weeping' is extremely artificial and a foolish formality. (86)

== Nazm page 86