FWP:

SETS == PARALLELISM

SOUND EFFECTS: {26,7}

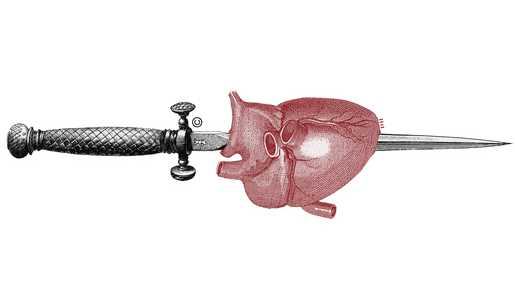

SWORD: {1,3}

The elegantly developed meanings provided by Faruqi all depend on the permutations of whether the speaker is the lover or the beloved; and of whether the use of knife and dagger to slash open breast and heart is considered a (normal or desperate) means to a desirable end, or a (fatal?) punishment for not having achieved that end.

Nazm and some other commentators treat this verse and the next one, {91,8}, as a sort of undeclared verse-set, and comment on both together. Either that, or else perhaps they consider these two verses to be a continuation of the verse-set that begins with {91,5} and definitely includes {91,6}. Since by convention only the beginnings of verse-sets are marked, it is left for the reader to decide where the verse-set ends. I am treating {91,5-6} as a verse-set, and {91,7} and {91,8} as two verses that simply have a lot in common-- much more with each other than with {91,5-6}.

It's a dramatic verse, and with its two imperative verbs, inshaa))iyah to the max. I especially like not only the effortless-seeming multiplicity of meanings, but also the harshly powerful sound effects that Faruqi points out.

Note for grammar fans: The first line has an intimate imperative ( tuu chiir ), while the second line has a familiar imperative ( tum chubho ). Yet the parallelism of structure is such that it doesn't seem at all reasonable to imagine two separate addressees. Surely the discrepancy is just meant to be casually colloquial (and of course it's metrically convenient).

Nazm:

That is, in the split-open heart and the blood-dripping eyelashes is such pleasure that if the knife of passion has not split the heart in two, then pierce the heart with a dagger and split the heart in two. And plunge a knife into the heart to make the eyelashes blood-dripping. For of what value is that breast in which the heart doesn't burn, and of what use is the heart that is not fire-scattering? To [metrically] shorten the he of mizhah is permissible, but [only] in Persian. (90)

== Nazm page 90