FWP:

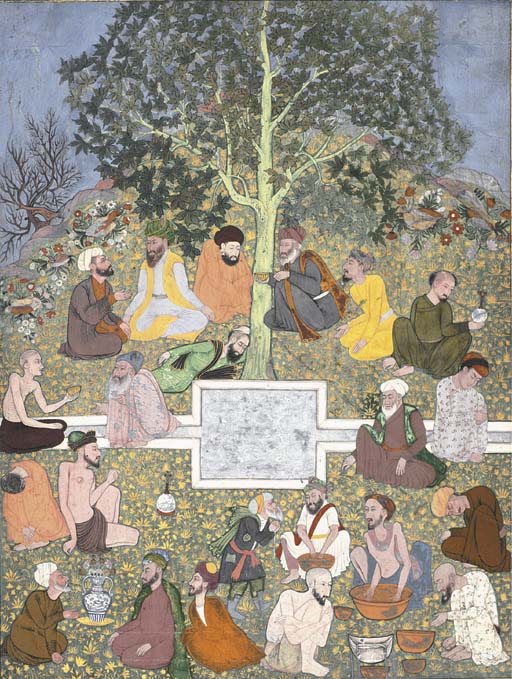

There could be several possible advantages in assuming the dress and guise of a Faqir, or religious mendicant.

One advantage: that the speaker is able to see the pious charity dispensed by the 'people of generosity', which pleases him as a show of their virtue. (And he wouldn't get to see it otherwise, since truly virtuous people do their good deeds privately rather than publicly.) He can admire their kindness and beneficence.

A second advantage: that he can enjoy the 'spectacle', the tamaashaa , created by the people of generosity-- especially the more ostentatious and worldly ones. Do they gather a great crowd of Faqirs around them? Do they make self-congratulatory speeches? Do they present their gifts one by one, with a great flourish? He can watch, and inwardly laugh.

A third advantage: that he is able to use it as a test, so that he can act as a kind of charity investigator. Who is truly generous, and who simply makes a show of it, and who doesn't give at all? Only now will he really know. For an explicit reference to such an investigation of 'hypocrisy', see {57,10x}.

A fourth advantage: that he is actually poor-- as in {26,5} or {10,7}-- but is too proud to admit it. By providing other reasons for assuming the role of a Faqir, he manages to obtain some alms, while also protecting his pride.

And of course, these advantages aren't mutually exclusive; many or even all of them might exist together.

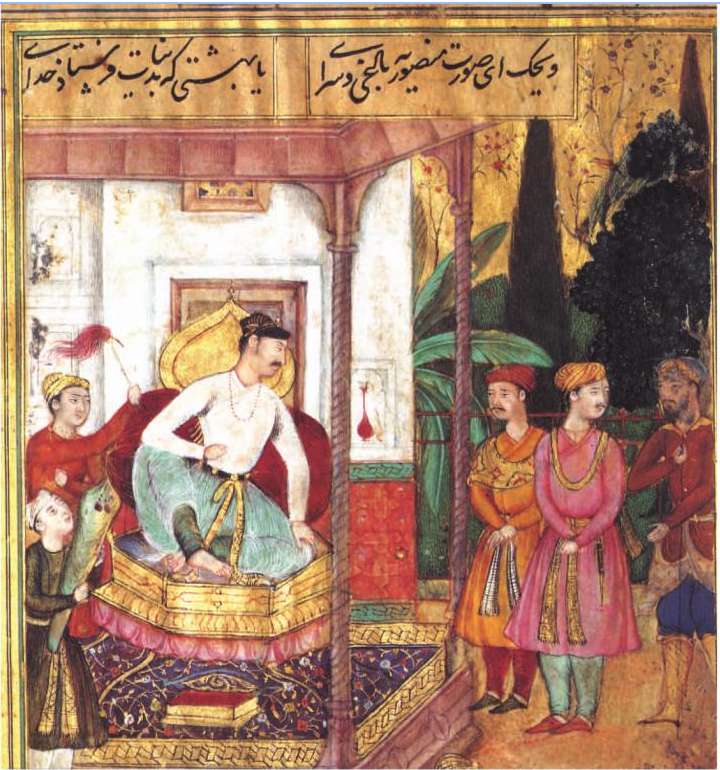

But then, the really amusing twist-- to what extent is the pious charity of the 'people of generosity' to be metaphorically converted into the way the powerful, well-endowed beloved treats her poor, needy lovers, as they crowd around her and beg for her attention? Can the lover urge her to be virtuously 'generous' in distributing her favors, just as she should be generous in distributing religious alms? Of course he can-- and quite shamelessly, he does.

Consider for example {24,3},

in which he explicitly asks for 'religious alms' of beauty: zakaat-e

;husn de , he begs the beloved. And there's the witty {162,9},

in which he suggestively urges the beloved 'do good-- it will be good for

you', and identifies this as 'the call of the Darvesh'.

None of this conflation feels theologically problematical, of course, because

the mischief level is so high, and it's all so clearly tongue-in-cheek. And

the final escape-hatch is always ready-- the beloved can always be God.

Nazm:

The meaning is that I don't have need of generosity, but I'm mad about the style of generosity, so in order to see it I've put on the guise of the Faqirs. (98)

== Nazm page 98