FWP:

SETS

BONDAGE: {1,5}

EYES {3,1}

Hali explains the basic reading: Jacob's eyes became the crevice-work in Joseph's cell in the sense that they were always open and always (somehow, mystically or implicitly) looking down upon him, watching over him.

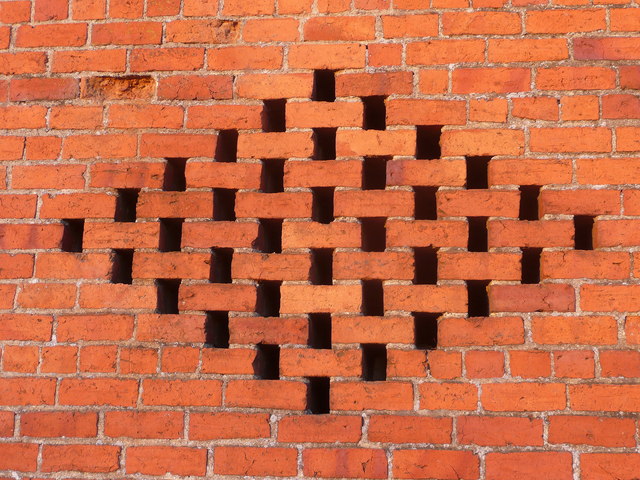

There's also a physical basis for the comparison: by ghazal convention, blind eyes are entirely white, since the pupil is believed to vanish or roll back in the head; and from inside a dark prison cell, the crevice-work (which is usually placed high up near the ceiling) will admit enough daylight so that it looks light or even white by contrast. For further discussion of the nature of this 'crevice-work', see {64,4}. Compare also {61,2}, in which Jacob's white eyes become something like whitewash in the cell. Another blind 'white eye' appears in the obscure {266x,2}.

This is preeminently a verse of mood. It's such a haunting image: the old man blind with weeping, deprived of all knowledge of his cherished son-- and still, somehow, watching over the beloved captive from afar. Can he really protect him? Surely not-- except in the sense that knowing you are loved like that is itself protection against some of the worst kinds of lostness. Doesn't this verse, in its eerie, evocative, way, celebrate the mystery of how parents love their children?

In the second letter quoted in {111,1},

Ghalib surely has the setting of this verse in mind. He likens his sufferings in the aftermath

of 1857 to those of Jacob: not only were his losses more terrible than Jacob's,

but he too was forced to live in painful anxiety and suspense-- many of his

loved ones were lost 'in such a way that no trace can be found of what has

become of them'.

Hali:

He has declared Jacob’s eyes to be crevice-work in the wall of the prison cell, because just as the crevice-work in the prison cell remained constantly open, similarly Jacob’s eyes, night and day, watched over Joseph. (151-52)

==Urdu text: Yadgar-e Ghalib, pp. 151-52