FWP:

SETS == MUSHAIRAH;

PARALLELISM

DIFFICULT/EASY: {6,5}

I would call this a sophisticated kind of 'mushairah verse', one that uses the parallelism of the two lines both to fulfill and to violate the hearers' expectations. As in many mushairah verses, the first line is broad, vague, abstract. Its two poles are 'grief' [ranj] and 'erasure of grief'. Yet, in a piquant effect available to both ear and eye, the 'grief' doesn't really seem to get erased-- it pops up again at the last moment. For the line is framed by two separate occurrences of the word, one at the very beginning and the other at the very end. They work like bookends, giving the line a feeling of symmetry and also emphasizing the single quality of 'grief' that is the pivot on which the line turns. Where will the poet go from here? Naturally, in a mushairah performance context, we have to wait a bit before we find out.

Then the first part of the second line sounds as if it could be preparing for a replay of the first line: so many difficulties fell on me that-- I no longer found them difficult; or, I no longer knew what difficulty was; or, 'difficulty' became erased; or some other such abstract formulation. As usual, we don't get the real punch until the very last moment-- and then we get it in a great, exultant rush. So many difficulties fell upon me-- kih aasaa;N ho ga))ii;N , that they became easy! The word aasaa;N itself sounds easy, fluent, prolongable, triumphant, amused, inviting to the ear. Its long vowels and nasalization lead elegantly into the refrain, ho ga))ii;N . And the word 'easy' also enacts the real vanishing of the difficulties; they don't recur the way ranj does in the first line, but are gone for good.

Isn't this an exhilarating verse? No doubt it can be recited in a rueful tone, and there's an underlying ruefulness to it anyway). But there's nothing lugubrious or morbid about it. It demands to be memorized and recited aloud. What a pleasure it would have been to be in the first mushairah that heard this whole remarkable ghazal-- a ghazal which in fact is unusually full of lovely, lively 'mushairah verses' like this one.

On the use of the perfect verb form as a subjunctive, see {35,9}.

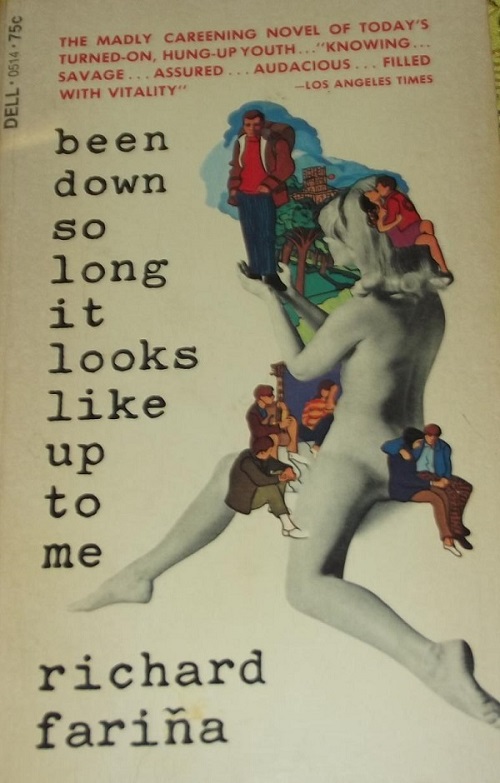

Here's the sixties generation's version of the same sentiment:

Hali:

This idea is absolutely novel, and it is not only an idea but rather a fact [faik;T]. And it has been expressed so excellently that nothing better can be imagined. To give a notion of the numerousness of difficulties by the total opposite, that is, by their becoming easy-- in reality, this is the height of 'elegance of exaggeration' [;husn-e mubaali;Gah], the equal of which has not been seen to this day.

==Urdu text: Yadgar-e Ghalib, p. 124