FWP:

SETS == A,B; IZAFAT

ISLAMIC: {10,2}

WINE: {49,1}

Bekhud Mohani does a fine job unpacking the possibilities of the first line, with all the implications of the wandering, the pawning, and so on. Since this is an 'A,B' verse, we're left to decide for ourselves whether the pawning is a preparation for the proposed feast, or a substitute for it, or simply an alternative activity that occupies the speaker's attention.

And what kind of a feast is it, anyway? Thanks to the ambiguities of the i.zaafat construction, there are several possibilities:

=A feast 'about', or celebrating, the atmosphere, climate, etc.; the commentators interpret this as a celebration of springtime, but of course the verse goes out of its way not to confirm any such idea. It might be celebrating the vitality and indispensability of wine itself. (Think of the whole 'wave of wine' ghazal, {49}.)

=A feast 'for' 'water and air', in which they are the honored guests. And with what could they more appropriately be regaled, than with wine? Wine, after all, is a superior cousin of water, and creates its own 'air' or 'atmosphere' of intoxication. (The lover is a thoughtful host: when he gives a feast for 'eyelashes', he serves them bits of liver: {233,2}.)

=A feast consisting 'of' 'water and air', in the sense that the supreme gifts of 'water and air' are provided to the guests-- in the form of wine, of course, that absolute necessity of the lover's life. There are verses in the 'wave of wine' ghazal, {49}, that equate wine with sustenance, growth, and flourishing.

In any case, this is a verse full of 'mischievousness' [sho;xii], as Bekhud Dihlavi observes. The complex layers of humiliation inflicted on the faqir's robe and the prayer-carpet, in order to provide complex layers of glorification of wine, are presented with such offhand casualness that they're a sheer delight to read. After all, the lover is really concerned chiefly with his social obligations, with the overdue feast (compare {233,1}); the means for arranging it are presented only by the way.

Compare the similar religious mischievousness of {131,1}.

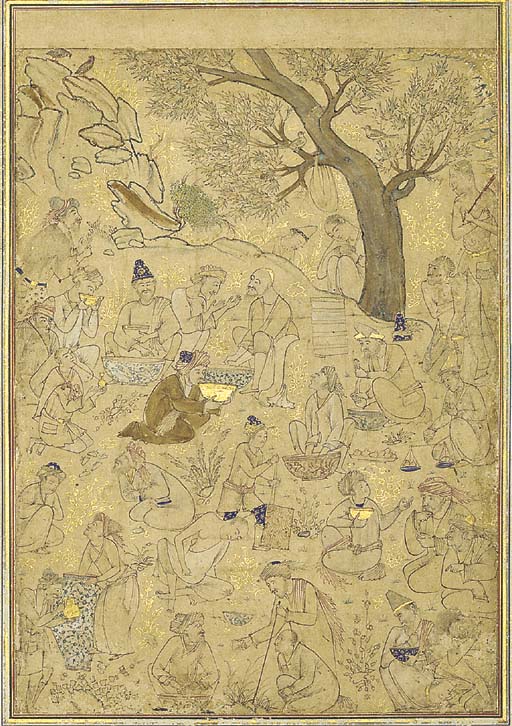

A gathering of darveshes (Deccan, c.1640)-- in a miniature painting that once belonged to Warren Hastings:

Nazm:

That is, it's a feast for the spring season. (162)

== Nazm page 162