FWP:

SETS == PARALLELISM; REPETITION

I was surprised to find that this verse and the next one, {215,7}, don't constitute an official verse-set, according to Arshi; I checked in both editions of his work to make sure. A number of the commentators treat it as a verse-set (as does Hamid), and it's easy to see why; Nazm gives the main reasons very clearly.

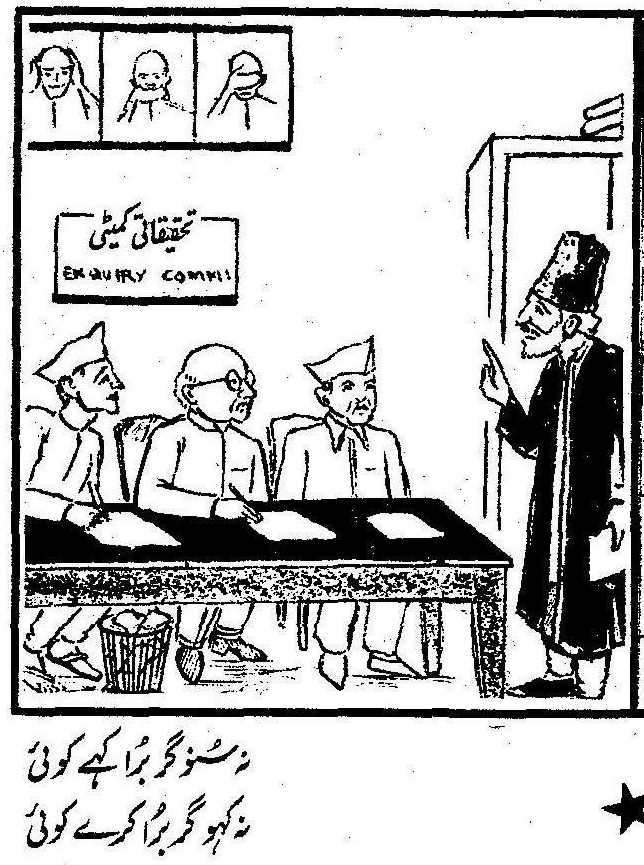

It might be tempting to get sidetracked into arguing morality here. If somebody abuses or insults or slanders someone, to (seem to) decline to listen is often a desirable and practical strategy. But if somebody does something bad-- that sounds dicey. What kind of thing? To keep silent if someone has stolen something may sometimes be justifiable, but should you keep silent if someone has committed murder, or some other terrible crime? The commentators seem generally to have no qualms about endorsing silence; their stance seems a dubious one. (See the cartoon below, which echoes my point.) But really this kind of argumentation will never get us any deeper into the verse.

It's worth noting that the commentators all read the verse as prescribing responses to behavior that has already taken place. But the future-subjunctive grammar seems to make an alternate time and causation arrangement possible as well. The first line could be read as 'if someone would, as a result of your listening, proceed to say something bad, then don't listen'; the second line would similarly become 'if someone would, as a result of what you said, proceed to do something bad, then don't speak'. In other words, don't become an instigator, a tempter; don't encourage or provoke others toward evil. This reading is both morally more attractive (to my mind at least), and more piquant.

But even so, is Ghalib really a poet of sententious moral maxims? A deeper source of pleasure in the verse is surely a structural one. The extremely obvious and maximized parallelism, made more conspicuous by the verse's stripped-down vocabulary and grammar, has an enigmatic pleasure of its own. Such ultimate simplicity surely suggests an underlying complexity. Moreover, the parallelism of the lines is both emphasized and undercut by a kind of escalation: the first line ends with a notion of someone's saying something [kahnaa], and the second line begins with a notion of your not saying something [kahnaa]. We thus notice a progression: first comes listening, then comes the crucial middle term of speaking, last comes doing. Is there some sequence or hierarchy we're meant to notice here? Are we meant to feel that you're always supposed to give one level less than you get? Are we meant to feel that you're always supposed to avoid provoking one level more? Beneath its surface of simplicity, he verse is so abstract and gnomic that it's impossible to wrest a single clear meaning from it.

Compare {209,5}.

(by Wahab Haidar)

Nazm:

[Commenting on this verse and {215,7}:] In both verses there is similarity of structure; beauty has been created in the construction. And the verbal repetition too is not devoid of pleasure. (244)

== Nazm page 244