FWP:

In the ghazal world, one of the things that the lover complains about is loss and departure: that the beloved might remove herself from his gaze, that she might go away. Well may the lover complain and lament about that! He complains either fearfully, before the dread event happens; or wretchedly, after the terrible loss has occurred. Why should he not, how could he not, complain? What could be worse?

This verse envisions something worse, for the one who has 'departed' is the semi-personified Expectation/Hope itself. The word tavaqq((u is feminine, and the use of the idiomatic u;Th jaanaa , with its literal meaning of 'to get up, stand up', can't help but suggest a feminine person who rises in order to leave (see the definition above). Thus we have the piquant reenactment of the beloved's departure-- only this time it's worse, for if the beloved departs then she might just conceivably return. But if Expectation/Hope departs, then by definition the loss is irrevocable, it's the end.

This quasi-personification also yields a more subtle secondary reading of the verse: when Expectation herself has departed, why would one complain about anyone else's departure? Expectation has already set the pattern, and no one else's departure, not even the beloved's, could be as dire-- so why complain about the also-rans?

For another verse that plays on the ultimate bleakness of the loss of hope, see {95,6}.

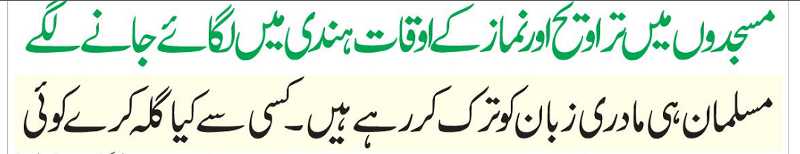

C. M. Naim has provided (July 2014) a newspaper headline that frames a cultural complaint by using-- and misquoting-- the second line of the verse:

Nazm:

How can anyone praise it [sufficiently] [us kii ta((riif kyaa kare ko))ii]! It is an extremely lofty theme, that can't be sufficiently praised. The meaning is that the person through whom expectation would have been cut off-- why then would anyone complain about him? Because there won't be any benefit from it, and hatred and enmity will be created. (245)

== Nazm page 245