Introduction

Nature’s rage cannot be stopped. However, by harnessing the modern technology as cell phone text messaging, we can mitigate its repercussions by galvanizing effective planning and action. And, in the process, we can save lives and livelihoods.

Background: 2004 Tsunami

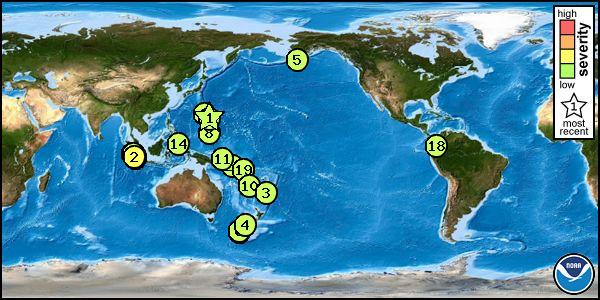

On December 26, 2004, the great Sumatra-Andaman earthquake with a

magnitude of 9.1- 9.3 occurred off the western coast of northern Sumatra, Indonesia. The quake triggered a series of tsunamis that devastated countries lining the Indian Ocean coast, killing 230,000 people and leaving more than 1.6 million displaced. According to relief agencies, one third of the dead were children.

Women's deaths were quadruple those of men.

|

| Animation of the tsunami ignited by the Sumatra-Andaman earthquake (credit: National Oceanic and Atmosphere Administration, NOAA) |

CASE STUDY: Sri Lanka

Text Messaging in Tsunami Aftermath

Much of the Sri Lankan coast was destroyed and more than 35,300 people were killed in the tsunami. Coordinating relief efforts and relaying up-to-date news was a challenge. Cell phone signals were too weak to hold a conversation, while telephone landlines were either destroyed or rendered unreliable. Relief workers found that SMS ("Short Message Service," or text messaging) was the next best option, and it proved to be a valuable communication tool to relay news and provide an on-the-ground assessment of who needed what. Sanjaya Senanayake, then a 23-year-old Sri Lankan television producer, realized he could send and receive text messages from his cell phone. He began sending SMS messages to his friends in India, who were also his co-editors for their blog

ChiensSansFronteres. Senanayake began reporting on the disaster and searching for his family and friends.

Samples of his entries are as follows:

"Found 5 of my friends, 2 dead. Of the 5, 4 are back in Colombo. The last one is stranded because of a broken bridge. Broken his leg. But he's alive. Made..."

"...contact. He got swept away but swam ashore. Said he's been burying people all day. Just dragging them off the beach and digging holes with his hands. Go..."

"...ing with gear to get him tomorrow morning. He sounded disturbed. Guess grave digging does that to you."

Senanayake's friends in India, in turn, posted Senanayake's experiences on their blogs. Thousands of

readers worldwide followed Senanayake's in-the-field experiences in the days and weeks following the tsunami aftermath.

SMS-based Tsunami Warning Systems Installed and Spur Evacuation

The Sri Lankan government established its

Disaster Management Centre (DMC) in the month following the 2004 tsunami to monitor potential natural disasters 24 hours a day. The UN Development Programme (UNDP) funded the project and provided technical assistance to ensure that DMC coordinators were present in all of Sri Lanka's 25 districts. Once a tsunami warning is issued, an alert from the DMC is sent to village chiefs, government agents, the military, police officers and media via SMS message. These agencies, in turn, contact citizens within their district to inform them of the alert via SMS, as well as by television and radio networks.

On

September 19, 2007, the DMC put their new technology to the test. Sri Lankans received a 20-word tsunami alert via SMS following a magnitude 7.9 earthquake off the southern coast of Sumatra: "Tsunami warning for Sri Lanka north, east and south coast. People asked to move away from coast - Disaster Management Center."

Mohideen Ajeemal, a fish wholesaler, was in Sainathimaruthu, a village on the eastern coast of Sri Lanka, when he received the text from his friend living in Colombo, the capital city. His village suffered heavy casualties following the 2004 tsunami; so his family, along with hundreds of others, quickly evacuated the coastline and moved further inland following the September alert.

Evaluation/Results

A Success with No Reported Casualties

The SMS alert was, overall, deemed a success. "We got the message out fast and people were evacuated," said Gamini Hettiarachchi, DMC director-general. No injuries or casualties were reported and citizens returned to their coastal villages over the course of the next three days.

Overburdened Networks

Telephone networks became jammed after the alert was issued due to heavy traffic, because citizens were talking on their mobiles as well as sending SMS messages. As a result, the Sri Lankan telecommunications authority now enforces the rule that subscribers may only communicate with family and friends via SMS messaging during national emergencies, so as not to overburden the networks.

Still Too Expensive for Impoverished Communities

The cost associated with mobile phone technology and access is beyond the

economic reach of many impoverished communities, including Sri Lanka's fishing communities. The purchase price of a mobile phone runs about 3,272 rupees (US$30) in Sri Lanka. However, it is the individual calling rates of 5.00 rupees (US$0.05) per minute that make the technology unaffordable to many Sri Lankans, who earn an average of less than 10,910 rupees (US$100) each month. Over 75 percent of the country's fishing fleet -- and fishing equipment -- was destroyed in the tsunami, a severe blow to Sri Lanka's already impoverished fishing community. A dramatic decrease in their income followed in the tsunami aftermath.

Judy Devadawsan is Director of WACOO (Women and Child Care Organization), a partner NGO of ActionAid Sri Lanka.

In a (cell phone) interview, she explained: <insert QuickTime file here>

Abuse of SMS-based Warning Systems by "Non-Official" Parties

Abuse of SMS-based Warning Systems by "Non-Official" Parties

On June 7, 2007, a tsunami warning SMS message—which wound up being a

hoax—sparked panic among Indonesia’s coastal communities in Nusa Tenggara province, and prompted thousands to retreat to higher ground. The message read: “The possibility is that a tsunami may take place on June 7.” However, regional meteorology and geophysics offices confirmed the SMS warning did not originate from their offices, as they normally would in a real emergency. Earthquakes and tsunamis cannot be predicted, but the Indonesian population was prone to panic. More than 168,000 people were killed in the 2004 tsunami in Indonesia’s Aceh province alone, making the country the worst hit in terms of casualties sustained.

Emergence of Free SMS-based Tsunami Early Warning Systems

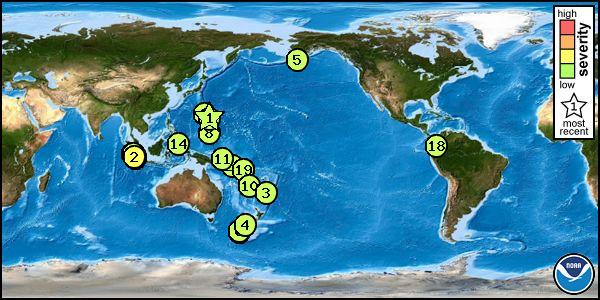

In the wake of the 2004 tsunami, volunteers in the technology field began creating tsunami early-warning systems, free of charge to subscribers. The

Integrated Tsunami Watcher Service website provides free live information about earthquakes and subsequent tsunamis for Indian sub-continent mobile phone users. According to their website, however, their services will be expanded to all coastal regions around the world. After submitting their mobile telephone numbers on the ITW website, subscribers will receive tsunami early-warning alerts via 160 alpha-numeric character SMS messages when the time calls.

|

| Tsunami SMS Messages Sent to Indicated Regions in Past 30 Days (Credit: Integrated Tsunami Watcher Service) |

Other Case Studies of Cell Phone Use in Emergencies

-

Syria: the

World Food Programme (WFP) sent SMS messages to Iraqi refugees in Syria in August 2007, informing them of food aid distribution.

-

Indonesia:

SMS hotlines installed for disaster victims (text in Bahasa Indonesia, the official language of the country).

-

Uganda: a "

Shared Access to Data" program launched by the Clinton Global Initiative, allowing cell phone connectivity among refugees in camps and settlements in nothern Uganda.

Abuse of SMS-based Warning Systems by "Non-Official" Parties

Abuse of SMS-based Warning Systems by "Non-Official" Parties