Digital History and September Eleven

Part of the historian’s task is to show the reader “Wie ist es eigentlich gewesen,” or “how things actually were.” But suppose you come up against some problem or another (as historians do) of sources. In history we typically talk of having too few sources. How can we know who Jesus really was, if many of our accounts come from the Bible? Can we know anything about our foreign policy matters presently, if so much of it is classified? This has, does and will plague historians forever.

But what about when we have the opposite problem? What if we have too much material to work with? Any reader of my blog will certainly have been alive and at least somewhat-conscious on the day of the September 11 attacks. Even though I was five years old, living on the opposite side of the continent, I remember seeing the Twin Towers up in smoke (both of them, as I had woken up just after the second plane hit). I remember being uncertain of what was going on. My reading skills were passable, but not enough to understand the headline or follow the ticker tape. What I remember was my mother being very curt as I got ready for class (given her own worries), talking about the attacks all day at school, and then coming home upset that I wouldn’t get to see Zoboomafoo on PBS Kids.

Now imagine taking experiences like mine, but reading tens of thousands more robust and more serious accounts of what people were thinking and feeling. And that’s just what is published and digitized! In the nascent age of the Internet there were a multitude of opinions. Publishing was and still is cheap. Almost anyone could write their thoughts like I’m doing now, and put them up for everyone to see. So how do you even begin to make sense of these things?

I was recently introduced to the digital humanities. And while it’s been a struggle finding topics appropriate for history that go beyond putting documents online (a challenge in its own right), I’ve found a number of interesting resources that could be of help – namely, The Programming Historian. One tool that had piqued my curiosity was Voyant, a data-mining tool that helps to reveal associations and patterns you might otherwise not have noticed.

This type of reading, where you read many documents with a computer, is called distant (or distance) reading. In this case, I am not interested in what one person or even twenty people had to say – that’s a close reading, and has long been a tool for historians and literary types alike, and generally brought humans to what are really the limits of our memory and capacity. Don’t get me wrong, close reading is perfect for typical historical research. But, it would be unreasonable for me to ask you to synthesize and draw any type of conclusion about ten thousand documents. Now with computers, however, I could begin to do just that and see what people are talking about generally.

Voyant is not the only method of doing distance reading – other technologies like Naïve Bayes categorization or topic modeling are more automatic but require much larger corpuses to be truly effective. I was unable to assemble a corpus of 500 to 1000 texts – but that’s no matter. Voyant provides its own insights while still making the user feel like they aren’t just relying on a computer for it all.

Although obvious to some, others might not consider it: the computer won’t always give good results, and it certainly won’t write a paper by itself. The more broad types of distance reading like Naïve Bayes or topic modeling fall under machine learning – a rapidly developing and constantly improving field in computer science. But even though it’s grown by leaps and bounds, as a field, machine learning is still very much in its infancy. Given that, it’s still up to the user to interpret the data, find the trends and then explain them, or at least point them out.

The first step in any digital history project is to build a corpus of text. Bigger usually is better, but Voyant is special in that it can still be helpful with anything from 1 to 1,000 and beyond documents. Using ProQuest, I found thirty different opinion pieces published mostly on September 12, with the vast majority of them from publications in the United States, and mostly from the Northeast megalopolis. Even though my corpus was, compared to other corpuses, rather small, it allowed me the time to go through and make sure each article was expressing some kind of opinion or take on the attacks.

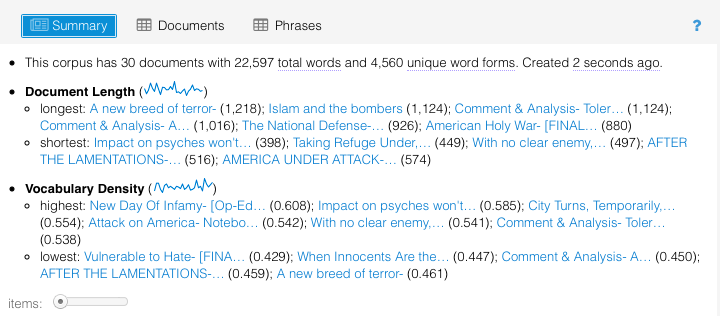

Voyant takes the documents you give it and then returns back a number of typical results you might expect. The Summary pane provides common data you might expect and is a good place to begin your analysis. For example, it might help you to see most frequent words in the corpus. Voyant offers that right off the bat. I’ve bolded one that immediately prompted questions in my mind:

Most frequent words in the corpus: world (105), people (64), attack (63), new (59), said (56).

Then there are the words that Voyant thinks are the most distinctive, as compared to the rest of the corpus. I’ve bolded some that might be ripe for analysis:

- When Innocents Are the…: legitimate (5), murder (5), palestinian (4), philosophy (3), acceptable (3).

- Islam and the bombers: al (11), qaeda (7), bin (9), laden (7), organisation (4).

- HEAL YOUR OWN HEART: erard (8), says (12), michigan (6), your (7), news (5).

- American Holy War- [FINAL…: require (4), cooperation (4), abroad (4), justice (3), efforts (3).

- Taking Refuge Under,…: i (19), van (5), started (4), inside (4), debris (4).

Now while it’s interesting to see that “world” was the most frequent term among the 4,560 unique words, it’s not surprising. Or is it? Of course, a fair number of the mentions are to the “World Trade Center” (19) or “World Trade Centre” (5).

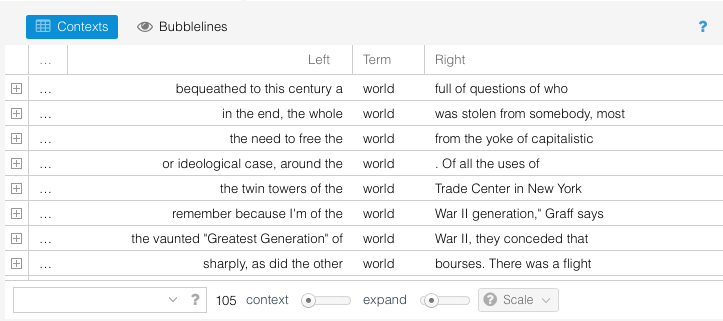

But that accounts for just 24 of 105 of the mentions of the word “world”. If we were to exclude those 24 mentions, then the word “world” appears 81 times, still keeping it at the top of the list. What gives? To answer that, Voyant offers a helpful tool called context, which gives us the surrounding words for any given term:

Thus we can see the term “world” comes in a number of different phrases – “a world full of questions,” “the whole world was stolen from somebody,” “the need to free the world from the yoke of capitalistic …,” “the rest of the world looks on aghast,” etc. Clearly there is something else going on, and this is where I think Voyant shines. Would I have picked up on this if I had read through the text by myself? Maybe – it does seem to be obvious in hindsight.

But Voyant makes it painfully clear that something is going on with the word “world,” and now it’s up to us humans to find out what. My initial impressions are that, as Americans, we viewed the event as some sort of world-defining moment. It may be interesting to compare this corpus to another one composed of primarily foreign opinions and reactions, and see how the word “world” is used there.

Similarly with our most distinct words – what does it mean that “legitimate” is distinct, or that “al qaeda” is distinct, or that pronouns like “i” and “your” are distinct? Particularly the inclusion of words “i” and “your” suggests that an inward self-reflection and self-help was not a part of the broader national ethos.

Getting back to the question of “Wie ist es…,” asking why “i” and “your” are distinct and uncommon word among the 9/11 diction could lead to something useful and interesting. Of course, it may also just reflect two weird articles in the corpus that happens to use first and second person language (which are uncommon in journalism) – either way, Voyant opens up a new way of thinking about the texts.

Finally, the Summary pane also includes and compares the length and density of each of the documents, which may be more useful to you than it is to me.

Also helpful are the visualizations that come with Voyant. A lot of the visualizations focus on a temporal aspect – for instance, the mini charts on the summary pane show changing word length and density across documents, presuming that the documents are arranged by date. It’s not useful if all your data comes from a particular day or two, like mine.

But say you’re trying to chart the changes in the works of a particular author – then the chronological charts become more useful when you can see where an author uses what words. Voyant comes loaded with the works of Shakespeare and Jane Austen in chronological order, showing you what texts, for instance, focus on what topics.

I invite you to see for yourself how obvious Voyant makes the similarities between Pride and Prejudice and Emma. Simply click here and look at the top right pane. Note how easily you can see that Pride and Prejudice and Emma use the word “Mr.” much more than any of her other texts. You can also play around with some of the other tools I’ve touched on and will touch on in this post to discover more similarities (or differences!) between the two novels.

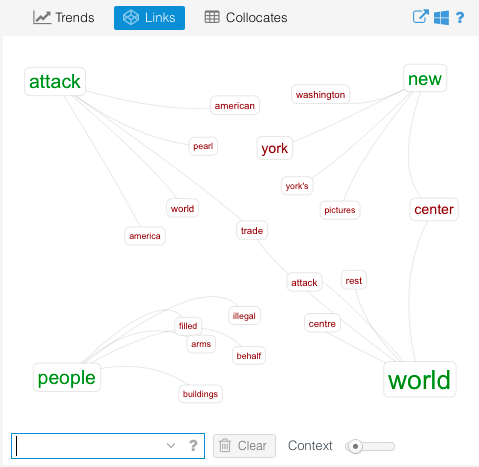

One last thing I’ll discuss is the “Links” visualization which can also provide new insights. Consider the following network of key words:

By highlighting relationships between words, Voyant allows us another way to revisit our corpus and find new trends we may not have known about. Of course, many of the links are obvious – “new” to “york”, or “world” to “trade” to “attack”. But some may not be so obvious – “attack” to “pearl” (highlighting numerous references to Pearl Harbor) or “new” to “pictures” (a reference to how people saw the attack unfold in real time). Others even more surprising: “new” to “center”, for instance, or “people” to “illegal” (here, as part of a criticism of the West’s implicit support and exploitation of human trafficking in the light of 9/11).

Of course with a corpus of only thirty documents, it’s easy enough to say that you could get a more synthesized and robust analysis just by getting out your highlighter and reading them. That, of course, is true. But what if you had one hundred? One thousand? Five thousand? Had I been able to, I would have downloaded hundreds of articles from ProQuest all at once, and begin to build a more robust corpus (unfortunately the mass-download service was not working when I was playing around with Voyant).

And of course, had I read these texts closely in the traditional way, it’s likely I would have missed the fact that the word “world” shows up so frequently in different contexts, or that an association between “new” to “pictures” would have been noteworthy; and it would have been impossible for me to know that a word as commonplace and innocuous as “legitimate” would be unique during 9/11. Using Voyant is not a matter of laziness – it’s a matter of getting at the bigger picture and finding trends that we may otherwise not see.

All that being said, these new methods of history won’t ever replace the historian, or at the very least, won’t replace the historian for a very long time. The tried and true method of discovering the past by collecting documents and organizing them to describe some ethos of some era will, I think, always be at the core of history. Think of digital tools in history like spell checker – while the checkers get more sophisticated daily and can catch “laed” for “lead,” it still can’t catch “lead” for “led” or “Price and Prejudice” for “Pride and Prejudice” (an error I made on a first draft of this post).

Perhaps, then, it is some small comfort that historians won’t be replaced by machines anytime soon. Even with these new machine-assisted techniques to guide our research, it’s still up to us to then go back and see if there truly is something there. Even in the above analyses, I had to go back and consider individual documents from my corpus, armed with a new knowledge of what to look for. While machine learning will be impressive, it will be a long time before it can come up with comprehensive ideas that summarize an ethos.

But let’s not forget that computers will be made indispensable for historical work in short order. With a new glut of information, an amount much more than any historian can even hope to look at and consider carefully, it may be time to seriously consider moving towards new modes and models of finding texts and patterns. And this is really what Voyant and tools like it are made to do – help us find patterns we may find interesting, prompting and inspiring new areas for investigation.